Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

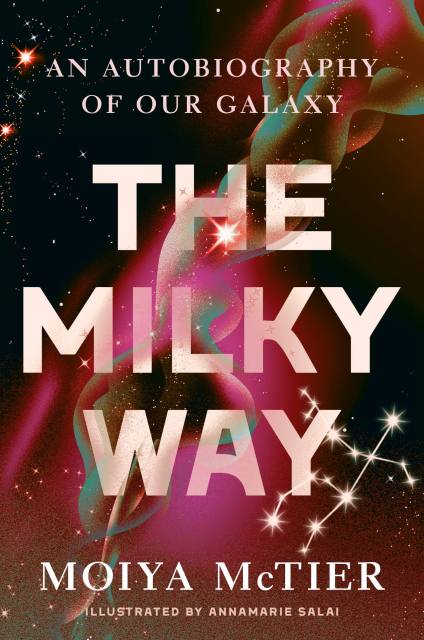

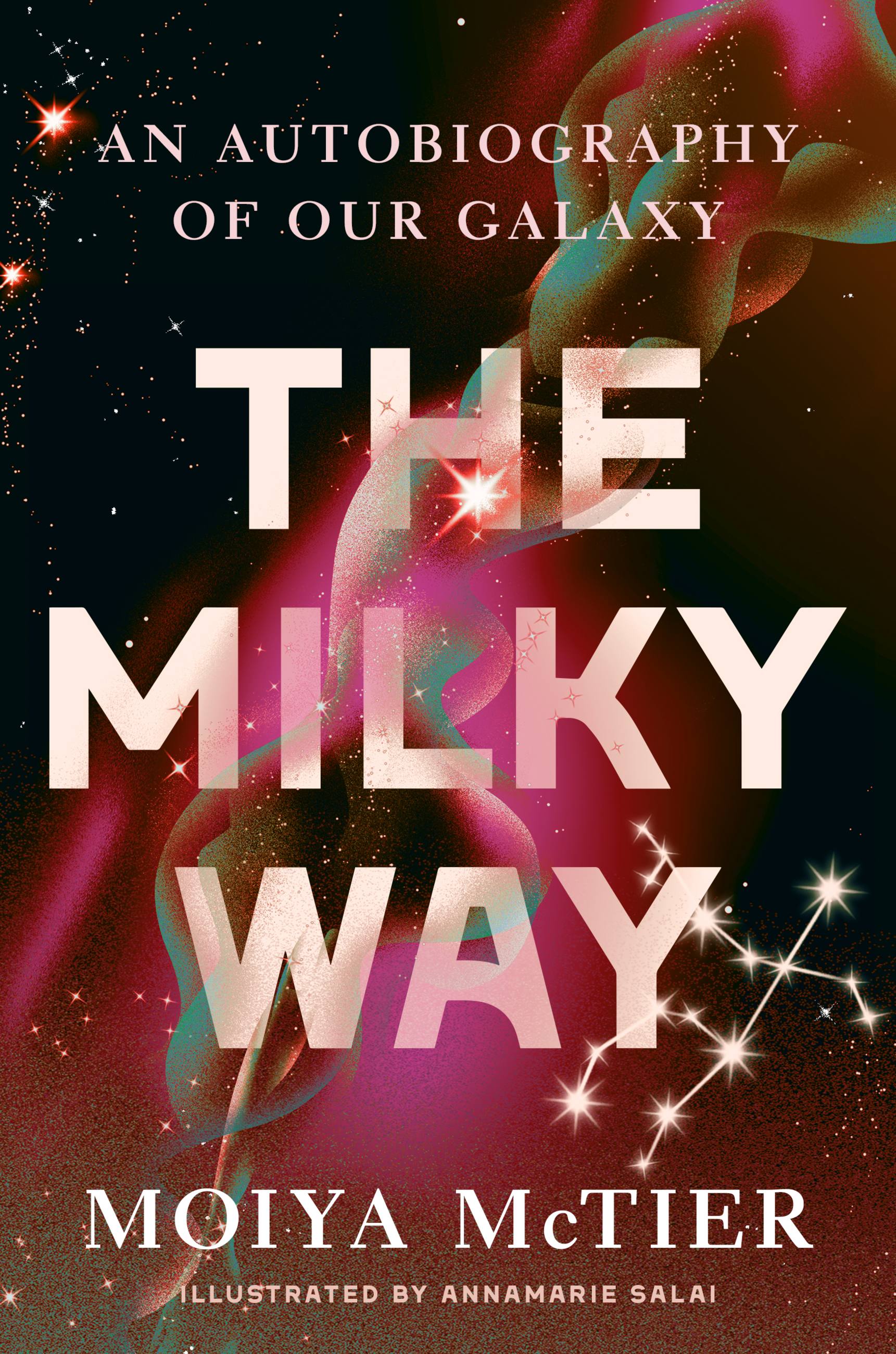

The Milky Way

An Autobiography of Our Galaxy

Contributors

By Moiya McTier

Formats and Prices

Price

$27.00Price

$34.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $27.00 $34.00 CAD

- ebook $11.99 $15.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $24.99

- Trade Paperback $18.99 $23.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around August 16, 2022. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

After a few billion years of bearing witness to life on Earth, of watching one hundred billion humans go about their day-to-day lives, of feeling unbelievably lonely, and of hearing its own story told by others, The Milky Way would like a chance to speak for itself. All one hundred billion stars and fifty undecillion tons of gas of it.

It all began some thirteen billion years ago, when clouds of gas scattered through the universe's primordial plasma just could not keep their metaphorical hands off each other. They succumbed to their gravitational attraction, and the galaxy we know as the Milky Way was born. Since then, the galaxy has watched as dark energy pushed away its first friends, as humans mythologized its name and purpose, and as galactic archaeologists have worked to determine its true age (rude). The Milky Way has absorbed supermassive (an actual technical term) black holes, made enemies of a few galactic neighbors, and mourned the deaths of countless stars. Our home galaxy has even fallen in love.

After all this time, the Milky Way finally feels that it's amassed enough experience for the juicy tell-all we've all been waiting for. Its fascinating autobiography recounts the history and future of the universe in accessible but scientific detail, presenting a summary of human astronomical knowledge thus far that is unquestionably out of this world.

NAMED A BEST BOOK OF 2022 BY PUBLISHERS WEEKLY AND SCIENCENET

NAMED A BEST AUDIOBOOK OF 2022 BY BOOKPAGE

NAMED A BEST AUDIOBOOK OF 2022 BY BOOKPAGE

Genre:

-

"Astrophysicist McTier delivers in her debut a delightful report on the Milky Way’s inner workings. . . McTier writes that her goal is to help people 'understand how ephemeral [our] existence is.' She succeeds smashingly. The result is truly stellar."Publishers Weekly, starred review

-

"[C]reative, humorous and enormously entertaining. . . As with any translation from another tongue, readers may marvel at the role of the translator in creating a book that is both informative and truly inspirational. Here, it's clear Dr. McTier has harnessed the sense of marvel she felt as a child, when she imagined the sun and moon as celestial parents who watched over her and talked to her on a regular basis. That childlike wonder, combined with her expertise in mythology and astronomy, makes her the perfect human to assist in telling this story."Bookpage, starred review

-

"As a character, the Milky Way is a cross between a Greek goddess and GLaDOS, the artificially superintelligent computer system from the Portal video-game series. She gossips about other galaxies, teaches us about her past and imparts a primer on astrophysics, all the while relishing every opportunity to throw shade on humankind’s egocentrism and closed-mindedness."Scientific American

-

"[A] one-of-a-kind look at our galaxy. . . Educational, informative, and original, this will leave readers eagerly anticipating McTier’s next book."Booklist

-

"McTier sprinkles humor throughout her whimsical look at the cosmos. . . [T]he author clearly knows her subject and delivers enough fascinating information to keep the pages turning."Kirkus Reviews

-

"It's about time we heard the story of the Milky Way in its own words. The good news is that our galaxy is not only ancient and majestic; it's also whimsical, amusing, and downright chatty. Moiya McTier's book is an entertaining introduction to some of the most profound features of our astrophysical neighborhood."Sean Carroll, New York Times bestselling author of Something Deeply Hidden

-

"If you want to learn about the Milky Way, who better to go to than the source? Well, up until now, the Galaxy hasn’t been talking – but all of that has changed! Turns out, the Milky Way has a sense of humor, an attitude, and, frankly, isn’t super impressed with us as of late. If you’re looking for a fun and unique way to learn about astrophysics – this is the book for you! "Kelly Weinersmith, New York Times bestselling author of Soonish

-

"A direct, fun, and charming mix of the science, folklore, and history of our Milky Way galaxy. And since that galaxy is technically composed at least in part by ME, I cannot help but take some of the credit."Ryan North, New York Times bestselling author of How to Invent Everything

-

“With The Milky Way: An Autobiography of Our Galaxy, Moiya McTier gives us an exciting romp through the universe from the perspective of a most unexpected guide: our local sentient collection of stars, gas, dark matter, planets, and its wayward humans. What an exciting way to learn about everything in the universe, from its earliest moments to star births and deaths. Only here will you learn what the Milky Way thinks of its neighbors. McTier invents the genre of cosmic gossip -- what fun it is!”Chanda Prescod-Weinstein, author of The Disordered Cosmos: A Journey into Dark Matter, Spacetime, and Dreams Deferred

-

"McTier's sharp wit and sharper intellect strike the perfect tone for this breezy take on the history of our galaxy. Truly the biggest tell-all story in the universe!"Paul M. Sutter, PhD, astrophysicists and author of Your Place in the Universe

-

“Brilliantly blending astrophysics and mythology, McTier has crafted an out of this world work of genius. The Milky Way is a remarkably clever, eye-opening entry into the astrophysics cannon that radically changes our perspective on space and our place in the vast cosmos. As entertaining as it is informative, this book is an essential read for earth dwellers who want a better understanding of our galactic home.”Stephon Alexander, author of Fear of a Black Universe

-

“A deliciously hilarious/irreverent and irresistible romp shimmering with astrophysics facts and cutting edge observations. A first “person” perspective that only an astrophysicist can provide. McTier’s humor and keen eye for detail pens the autobiography that our home galaxy deserves!”Brian Keating, Chancellor’s Distinguished Professor of Physics at UC San Diego and author of Losing the Nobel Prize and INTO THE IMPOSSIBLE: Think Like a Nobel Prize Winner

- On Sale

- Aug 16, 2022

- Page Count

- 256 pages

- Publisher

- Grand Central Publishing

- ISBN-13

- 9781538754153

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use