Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

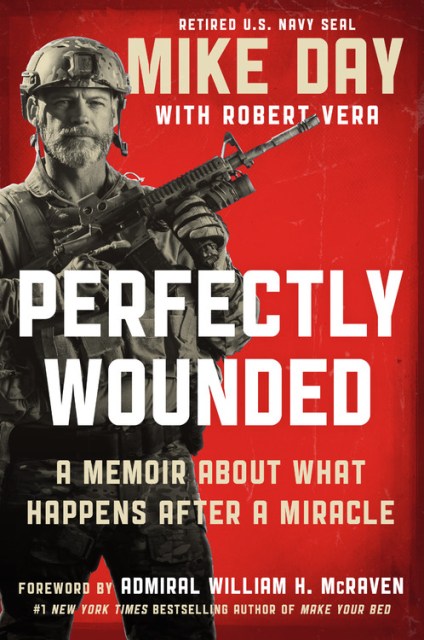

Perfectly Wounded

A Memoir About What Happens After a Miracle

Contributors

By Mike Day

With Robert Vera

Foreword by Admiral William H. McRaven

Formats and Prices

Price

$28.00Price

$35.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $28.00 $35.00 CAD

- ebook $14.99 $19.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around June 9, 2020. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

The incredible true story of former Navy SEAL Mike Day, who survived being shot twenty-seven times while deployed in Iraq.

On the night of April 6, 2007, in Iraq’s Anbar Province, Senior Chief Mike Day, his team of Navy SEALs, and a group of Iraqi scouts were on the hunt for a high-level al Qaeda cell. Day was the first to enter a 12×12 room where four terrorist leaders were waiting in ambush. When the gunfight was over, he took out all four terrorists in the room, but not before being shot twenty-seven times and hit with grenade shrapnel. Miraculously, Day cleared the rest of the house and rescued six women and children before walking out on his own to an awaiting helicopter, which flew him to safety.

While in the hospital, the Navy SEAL lost fifty-five pounds in two weeks. It took almost two years for Day to physically recover from his injuries, although he still deals with pain. Like so many veterans, doctors diagnosed Day with Post Traumatic Stress Disorder and Traumatic Brain Injury — the invisible wounds of war.

Perfectly Wounded is the remarkable story of an American hero whose incredible survival defies explanation, and whose blessed life of service continues in the face of unimaginable odds.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Jun 9, 2020

- Page Count

- 240 pages

- Publisher

- Grand Central Publishing

- ISBN-13

- 9781538701836

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use