Promotion

Shop now and save 20% on your back-to-school purchases & get free shipping on orders $45+ Use code: SCHOOL24

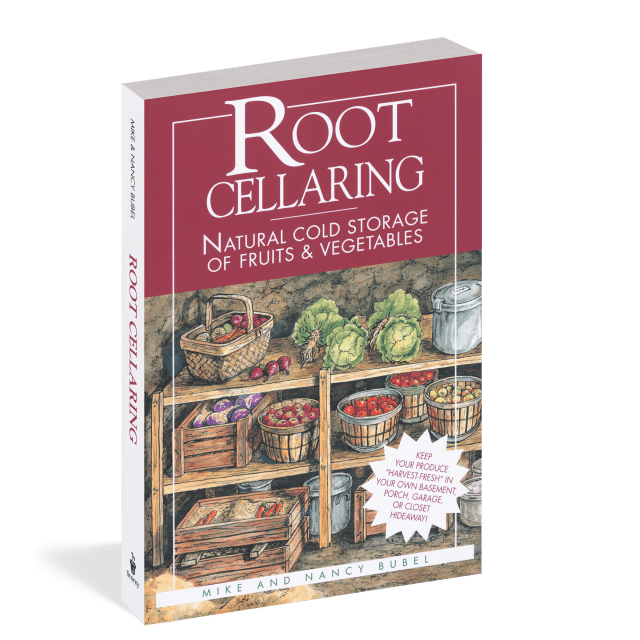

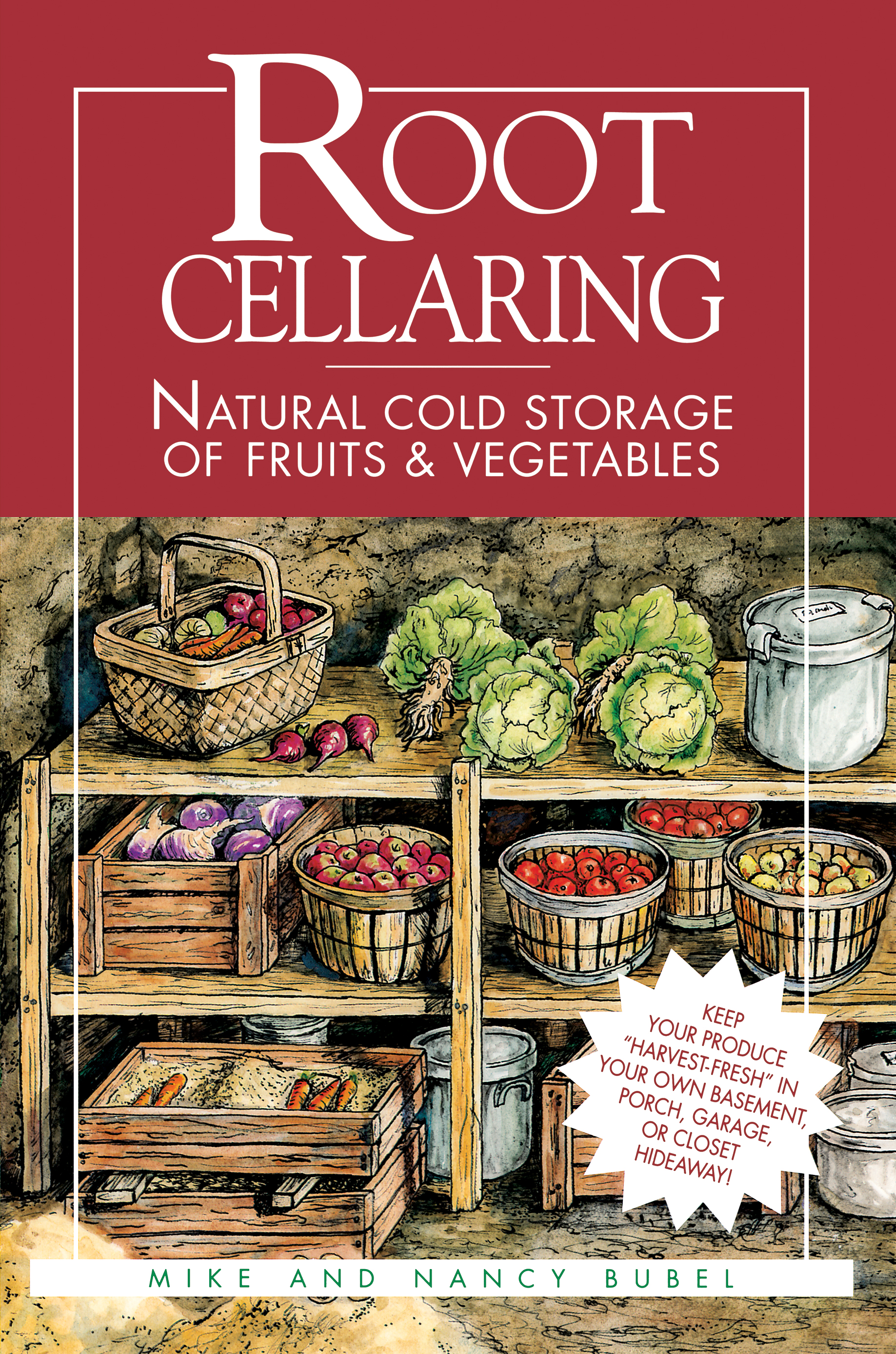

Root Cellaring

Natural Cold Storage of Fruits & Vegetables

Contributors

By Mike Bubel

By Nancy Bubel

Formats and Prices

Price

$16.99Price

$22.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $16.99 $22.99 CAD

- ebook $11.99 $15.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around January 9, 1991. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

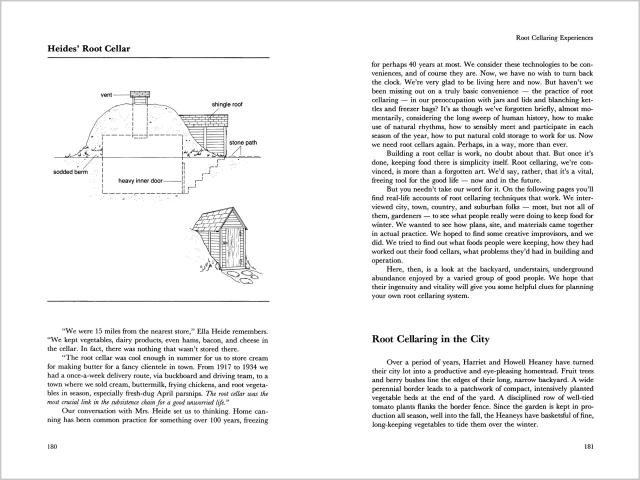

Stretch the resources of your small backyard garden further than ever before, without devoting hundreds of hours to canning! This informative and inspiring guide shows you not only how to construct your own root cellar, but how to best use the earth’s naturally cool, stable temperature as an energy-saving way to store nearly 100 varieties of perishable fruits and vegetables.

-

“…the most complete book on the subject you are likely to find.”Backwoods Home Magazine“…a book that has become a durable classic – a manual that delivers detailed guidelines for storing fruits and vegetables in the most simple way possible.”The Province (Vancouver, British Columbia)“The name Bubel is synonymous with practical, hands-on experience…I highly recommend Root Cellaring. It’s the only book you need on the subject.”Maine Organic Farmer Gardener

-

"The most complete book on the subject you are likely to find."

- On Sale

- Jan 9, 1991

- Page Count

- 320 pages

- Publisher

- Storey

- ISBN-13

- 9780882667034

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use