Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

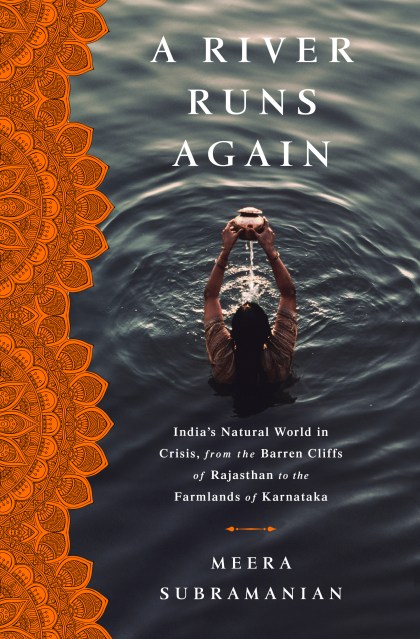

A River Runs Again

India's Natural World in Crisis, from the Barren Cliffs of Rajasthan to the Farmlands of Karnataka

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$15.99Price

$20.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $15.99 $20.99 CAD

- Hardcover $28.00 $35.00 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around August 25, 2015. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

In this lyrical exploration of life, loss, and survival, Meera Subramanian travels in search of the ordinary people and microenterprises determined to revive India’s ravaged natural world: an engineer-turned-farmer brings organic food to Indian plates; villagers resuscitate a river run dry; cook stove designers persist on the quest for a smokeless fire; biologists bring vultures back from the brink of extinction; and in Bihar, one of India’s most impoverished states, a bold young woman teaches adolescents the fundamentals of sexual health. While investigating these five environmental challenges, Subramanian discovers the stories that renew hope for a nation with the potential to lead India and the planet into a sustainable and prosperous future.

Genre:

-

“This is investigative journalism as story: fact-filled but optimistic, rueful and inviting. The author writes with warm intelligence, and she challenges readers.… In each chapter, as well, Subramanian offers specific antidotes as anecdotes, narrating in a measured, conversational, welcoming voice… Each of the stories is comprehensive while nimble, as well as provocative. Promising prescriptions to five of India's baneful environmental cases—right thinking and accusatory in all the right places.” —Kirkus Reviews

“The result of her immersion in the efforts of so many dedicated individuals is a hopeful narrative about good people doing hard work to improve the lives of others. Subramanian's strong journalist ethic shines through in the penetrating questions she poses and the baleful eye she casts on those who would shrug off her perceptive observations about the clash between traditional practices and modern life. A significant and valuable inquiry into twenty-first-century India.” —Booklist

“By embedding numerous facts and data about India's inhabitants into her engrossing narrative, Subramanian has created a work that belongs in all environmental collections.” —Library Journal -

"Subramanian's writing brings a positive approach to India's problems...Throughout this book, Subramanian takes us on a true journey of learning and she does it in a quiet, thorough, and knowledgeable manner. She educates us on the evolution of the problem and finally, through small narratives of those she met along the way—everyday farmers, wives, volunteer workers, and government employees, we learn of how they have embraced the progressive ideas as ways to save India's ecology." —New York Journal of Books

“What happens in India may turn out—even more than China—to be the key to the kind of environmental future the planet faces. Very few people are qualified to tell the story with as much clarity, compassion, and character-driven power as Meera Subramanian.” —Bill McKibben, author of Oil and Honey: The Education of an Unlikely Activist

“This is a necessary book. And Meera Subramanian is the perfect person to be writing it.” —Suketu Mehta, author of Maximum City: Bombay Lost and Found

“A River Runs Again is at once sweeping and intimate—a smart, informative, richly reported book full of memorable characters.” —Elizabeth Kolbert, author of The Sixth Extinction: An Unnatural History -

"Meera Subramanian's A River Runs Again tells five tales of India at the crossroads – a filigree of cautionary and celebratory stories – voiced with dignified passion...Subramanian navigates these rough waters between baneful emergencies and precarious signs of enlightened attitudes with the right degree of cautious optimism." —Christian Science Monitor

“Exemplary...Subramanian's writing is thoughtful and often lyrical as she balances current science with narrative journalism from her travels, switching modes to great effect. While reporting on environmental issues can sometimes overwhelm or burden the reader with guilt, Subramanian thwarts this risk by providing refreshing glimpses of individuals and organizations working against the problems India faces. Her work is engaging, informative, and eminently readable.” —Publishers Weekly, starred review

- On Sale

- Aug 25, 2015

- Page Count

- 352 pages

- Publisher

- PublicAffairs

- ISBN-13

- 9781610395311

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use