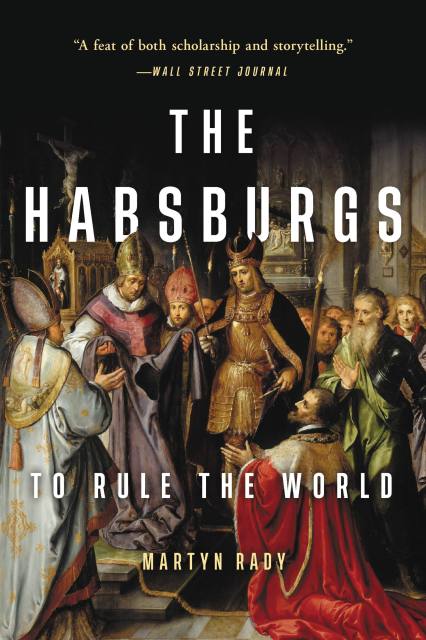

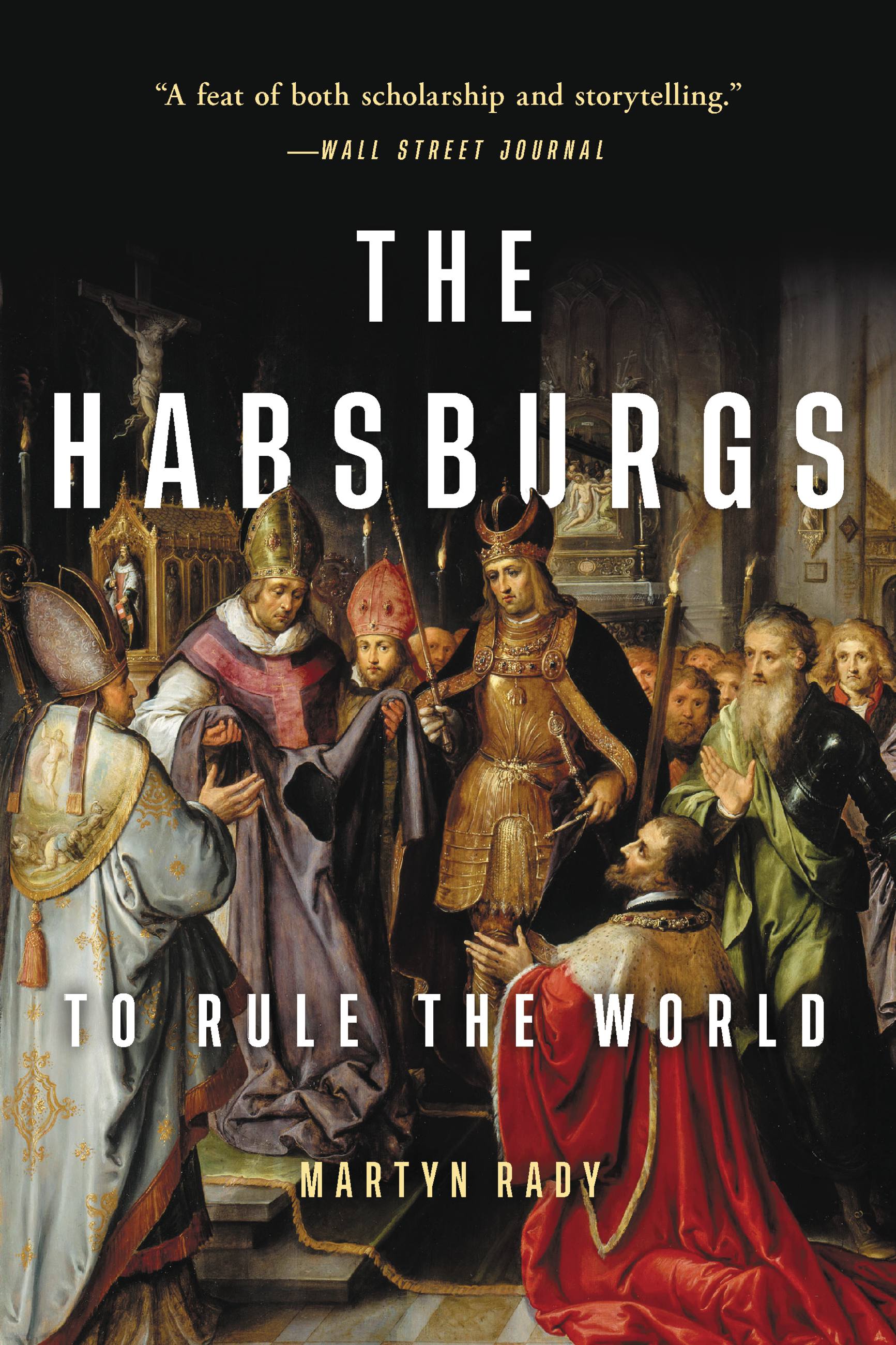

The Habsburgs

To Rule the World

Contributors

By Martyn Rady

Formats and Prices

Price

$21.99Price

$28.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $21.99 $28.99 CAD

- ebook $12.99 $16.99 CAD

- Hardcover $32.00 $40.00 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around May 10, 2022. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

“A feat of both scholarship and storytelling” (Wall Street Journal)—the definitive history of a powerful family dynasty who dominated Europe for centuries.

In The Habsburgs, Martyn Rady tells the epic story of a dynasty and the world it built—and then lost—over nearly a millennium. From modest origins, the Habsburgs gained control of the Holy Roman Empire in the fifteenth century. Then, in a few decades, their possessions rapidly expanded to take in a large part of Europe, stretching from Hungary to Spain, and parts of the New World and the Far East. The Habsburgs dominated Central Europe through the First World War.

Historians often depict the Habsburgs as leaders of a ramshackle empire. But Rady reveals their enduring power, driven by the belief that they were destined to rule the world as defenders of the Roman Catholic Church, guarantors of peace, and patrons of learning. This is the remarkable history of a dynasty that forever changed Europe and the world.

In The Habsburgs, Martyn Rady tells the epic story of a dynasty and the world it built—and then lost—over nearly a millennium. From modest origins, the Habsburgs gained control of the Holy Roman Empire in the fifteenth century. Then, in a few decades, their possessions rapidly expanded to take in a large part of Europe, stretching from Hungary to Spain, and parts of the New World and the Far East. The Habsburgs dominated Central Europe through the First World War.

Historians often depict the Habsburgs as leaders of a ramshackle empire. But Rady reveals their enduring power, driven by the belief that they were destined to rule the world as defenders of the Roman Catholic Church, guarantors of peace, and patrons of learning. This is the remarkable history of a dynasty that forever changed Europe and the world.

Genre:

-

"A feat of both scholarship and storytelling.... It's not hard to see current parallels to this story.... In an era of schisms, America needs a unifying idea of itself as something greater than the sum of its parts. If the Habsburgs could last for a millennium, surely a constitutional republic can."Wall Street Journal

-

“Glory, grief, loss – and incest – are all covered in this panoramic account that makes more sense of the great European dynasty than its rulers often did.”The Guardian

-

"Martyn Rady's history of this peculiar family is deeply informed, elegantly written and a joy to read."Evening Standard (UK)

-

"Rady is a lucid and elegant writer... It is impossible to imagine a more erudite and incisive history of this fascinating, flawed and ultimately tragic dynasty."The Times (UK)

-

"A Rolls Royce of a narrative that motors through ten centuries of history with an effortlessness that belies the intellectual horsepower beneath the bonnet."Literary Review (UK)

-

"Probably the best book ever written on the Habsburgs in any language.... Lucid, comprehensive and witty, it is not merely a pleasure to read but a complete education. Students, scholars and the general reader will never find a better guide to Habsburg history."Times Literary Supplement (UK)

-

"This admirably compact, exceptionally well-written survey will probably be the standard one-volume history of the Habsburg dynasty for years to come."Library Journal

-

"This comprehensive account provides an insightful overview of seven centuries of European history."Publishers Weekly

-

"A sweeping chronicle of the rise and fall of the Habsburg dynasty."Kirkus

-

"The Habsburgs is gripping, colorful, and dramatic but also concise, scholarly, and magisterial. Martyn Rady recounts the story of Europe's greatest dynasty that ruled an empire, on which the sun never set, from Peru to the Philippines. Revealing a key player in world history for almost a thousand years, The Habsburgs is a chronicle of high politics and family intimacy involving religion, murder, incest, madness, suicide, assassination. History on an epic scale!"Simon Sebag Montefiore, author of The Romanovs and Jerusalem: The Biography

-

"The Habsburgs were once Europe's foremost royal family. Rady tells their story with verve and authority, casting a curious eye over their eccentricities and peccadilloes while all the time revealing their extraordinary influence and global vision. A fascinating read!"Alexander Watson,author of The Fortress: The Siege of Przemysl and the Making of Europe'sBloodlands

-

"This is a first global history of Europe's most famous and durable dynasty, chronicling its exploits with great panache over nearly a millennium of rule across wide swathes of the continent and beyond. Martyn Rady writes incisively and judiciously, drawing on much recent international scholarship in a range of languages to illustrate multiple facets of Habsburg governance in theory and practice. At the same time his text is accessible and entertaining, his ready wit providing a delectable counterpoint to the notorious humourlessness of so many of the dynasts he examines."Robert Evans, Regius Professor of History Emeritus at the University of Oxford

-

"A tour de force. Thorough, accessible and resolutely erudite, this is the volume that this vitally important subject so desperately needed. Martyn Rady should be congratulated."Roger Moorhouse, author of Poland 1939: The Outbreak of World War II

-

"Martyn Rady has written a splendid account of the grandest old dynasty of Europe: the Habsburgs. With wit and firm opinion, he takes the reader on something akin to a tour of the Wunderkammer of the dynasty's many-centuries-long career. Including vampires, an empress's waist size, and cocaine-laced health drinks, Rady's narrative glitters with apt quotes and telling, often ironic details. One does not have to agree entirely with his distinct point of view to recognize that this is an extremely well-founded, most informative, and highly entertaining introduction to a major, and unjustly neglected, part of European history."Steven Beller, authorof The Habsburg Monarchy 1815-1918

- On Sale

- May 10, 2022

- Page Count

- 432 pages

- Publisher

- Basic Books

- ISBN-13

- 9781541644519

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use