Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

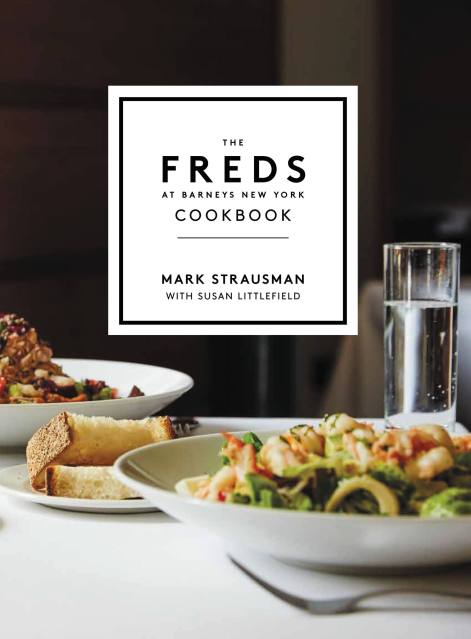

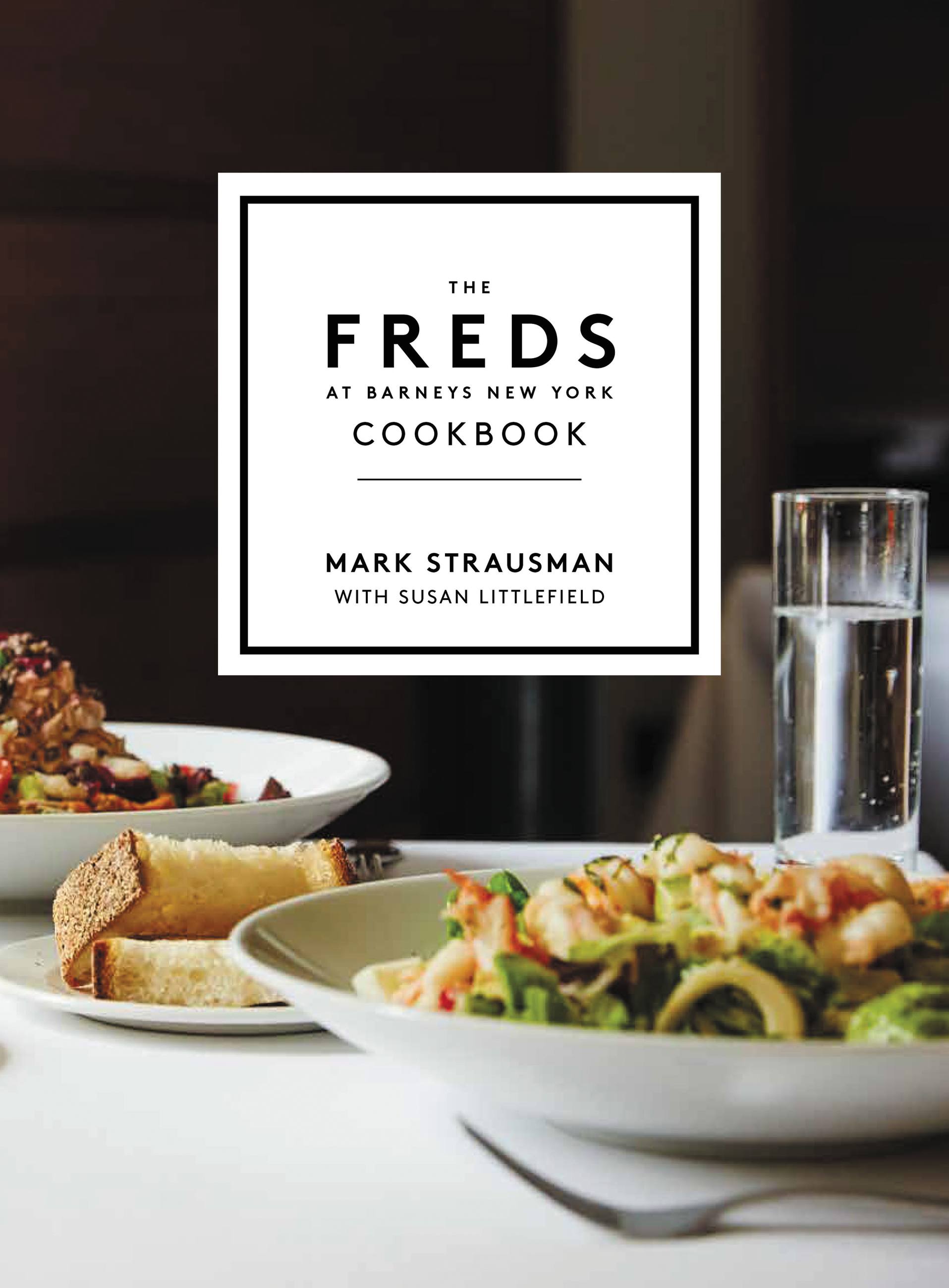

The Freds at Barneys New York Cookbook

Contributors

By Susan Littlefield

Formats and Prices

Price

$16.99Price

$21.99 CADFormat

Format:

ebook $16.99 $21.99 CADThis item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around April 24, 2018. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

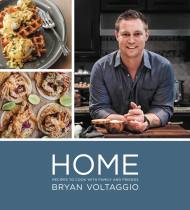

The definitive cookbook by the celebrated chef and managing director of Freds at Barneys New York, one of New York's most beloved restaurants with locations in Los Angeles and Chicago.

Barneys New York, with its flagship store on Madison Avenue, is a world-famous cutting-edge fashion destination, and a true New York phenomenon. And since 1996, Barneys' restaurant Freds at Barneys New York–named after found Barneys Pressman's son Fred–has been offering in food what Barneys offers in fashion: a luxury destination that provides a level of personal service second to none, where the food keeps their celebrity clientele coming back for more.

In The Freds at Barneys Cookbook, Strausman invites you into the kitchen of this restaurant institution and teaches you how to bring a piece of New York chic into your own home. Whether its the Belgian Fries or Estelle's Chicken Soup, Mark's Madison Avenue Salad or Chicken Paillard, Traditional Bolognese (or Vegan!) or Cheese Fondue Scrambled Eggs, this cookbook commemorates all of the delicious recipes Freds has served over the years at the Madison Avenue, Chelsea, Beverly Hills, and Chicago locations.

Barneys New York, with its flagship store on Madison Avenue, is a world-famous cutting-edge fashion destination, and a true New York phenomenon. And since 1996, Barneys' restaurant Freds at Barneys New York–named after found Barneys Pressman's son Fred–has been offering in food what Barneys offers in fashion: a luxury destination that provides a level of personal service second to none, where the food keeps their celebrity clientele coming back for more.

In The Freds at Barneys Cookbook, Strausman invites you into the kitchen of this restaurant institution and teaches you how to bring a piece of New York chic into your own home. Whether its the Belgian Fries or Estelle's Chicken Soup, Mark's Madison Avenue Salad or Chicken Paillard, Traditional Bolognese (or Vegan!) or Cheese Fondue Scrambled Eggs, this cookbook commemorates all of the delicious recipes Freds has served over the years at the Madison Avenue, Chelsea, Beverly Hills, and Chicago locations.

Genre:

-

"There are...many offerings inspired by [Strausman's] days as chef at Italian restaurant Campagna and his love of Italian food...Strausman encourages even reluctant cooks with clear directions and many helpful cooking tips. [THE FREDS AT BARNEYS NEW YORK COOKBOOK] is a wonderful peek inside the popular restaurant."Publishers Weekly

-

"Many credit Chef Mark Strausman's '80s summer restaurant Sapore di Mare in Wainscott as being "the first Hamptons pop-up." That credit probably belongs to Chef Henry Soulé's takeover of East Hampton's The Hedges for the summer of 1954. But there's no question that Strausman's pioneering farm-to-table approach at Sapore di Mare left a lasting mark."Dan's Papers

-

"The intriguing tale of how the drab downstairs eatery in the flagship Madison Avenue Barneys New York morphed into the brightly expansive top-floor Freds is well-told in the detailed, entertaining and wholly practicalThe Freds at Barneys New York Cookbook... Written with Susan Littlefield, it chronicles [Mark] Strausman's 22-year role as the guiding toque, giving much due credit to the store's savvy, fashion-minded guiding hands, Fred Pressman, son of founder Barney Pressman, and later, Barney's grandsons, Gene and Bob...I propose a toast to Freds and Mark Strausman with the establishment's signature cocktail, naturally, the Fred and Ginger."Mimi Sheraton

-

"But more than a cooking manual, the book comes to us as a memoir and artifact..."From The New York Times feature on Freds At Barneys

- On Sale

- Apr 24, 2018

- Page Count

- 304 pages

- Publisher

- Grand Central Life & Style

- ISBN-13

- 9781455537778

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use