Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

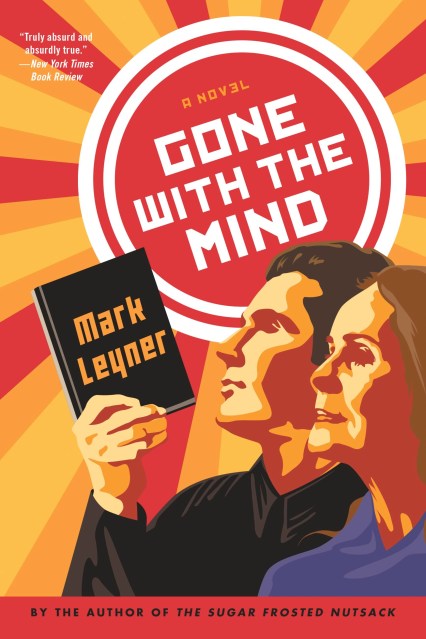

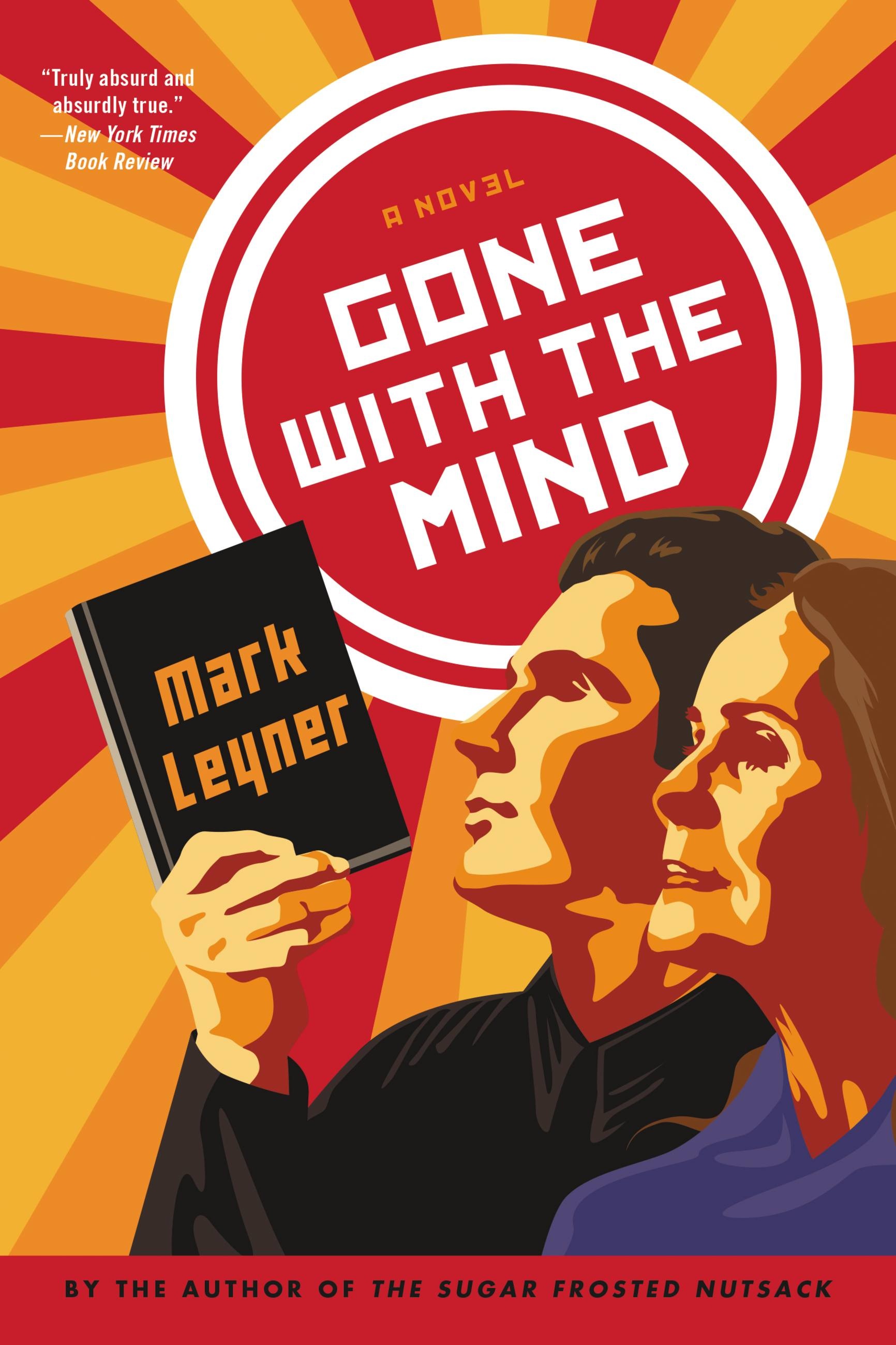

Gone with the Mind

Contributors

By Mark Leyner

Formats and Prices

Price

$19.99Price

$25.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $19.99 $25.99 CAD

- ebook $9.99 $12.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around November 29, 2016. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

The blazingly inventive fictional autobiography of Mark Leyner, one of America’s “rare, true original voices” (Gary Shteyngart).

Dizzyingly brilliant, raucously funny, and painfully honest, Gone with the Mind is the story of Mark Leyner’s life, told as only Mark Leyner can tell it. In this utterly unconventional novel — or is it a memoir? — Leyner gives a reading in the food court of a New Jersey shopping mall.

The “audience” consists of Mark’s mother and some stray Panda Express employees, who ask a handful of questions. The action takes place entirely at the food court, but the territory covered in these pages has no bounds. A joyride of autobiography, cultural critique, DIY philosophy, biopolitics, video games, demagoguery, and the most intimate confessions, Gone with the Mind is both a soulful reckoning with mortality and the tender story of the relationship between a complicated mother and an even more complicated son.

At once nostalgic and acidic, deeply humane, and completely surreal, Gone with the Mind is a work of pure, hilarious genius.

Dizzyingly brilliant, raucously funny, and painfully honest, Gone with the Mind is the story of Mark Leyner’s life, told as only Mark Leyner can tell it. In this utterly unconventional novel — or is it a memoir? — Leyner gives a reading in the food court of a New Jersey shopping mall.

The “audience” consists of Mark’s mother and some stray Panda Express employees, who ask a handful of questions. The action takes place entirely at the food court, but the territory covered in these pages has no bounds. A joyride of autobiography, cultural critique, DIY philosophy, biopolitics, video games, demagoguery, and the most intimate confessions, Gone with the Mind is both a soulful reckoning with mortality and the tender story of the relationship between a complicated mother and an even more complicated son.

At once nostalgic and acidic, deeply humane, and completely surreal, Gone with the Mind is a work of pure, hilarious genius.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Nov 29, 2016

- Page Count

- 256 pages

- Publisher

- Back Bay Books

- ISBN-13

- 9780316323277

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use