Promotion

Use code FALL24 for 20% off sitewide!

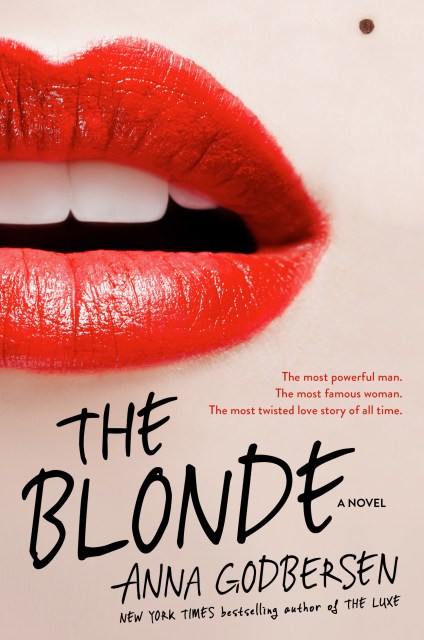

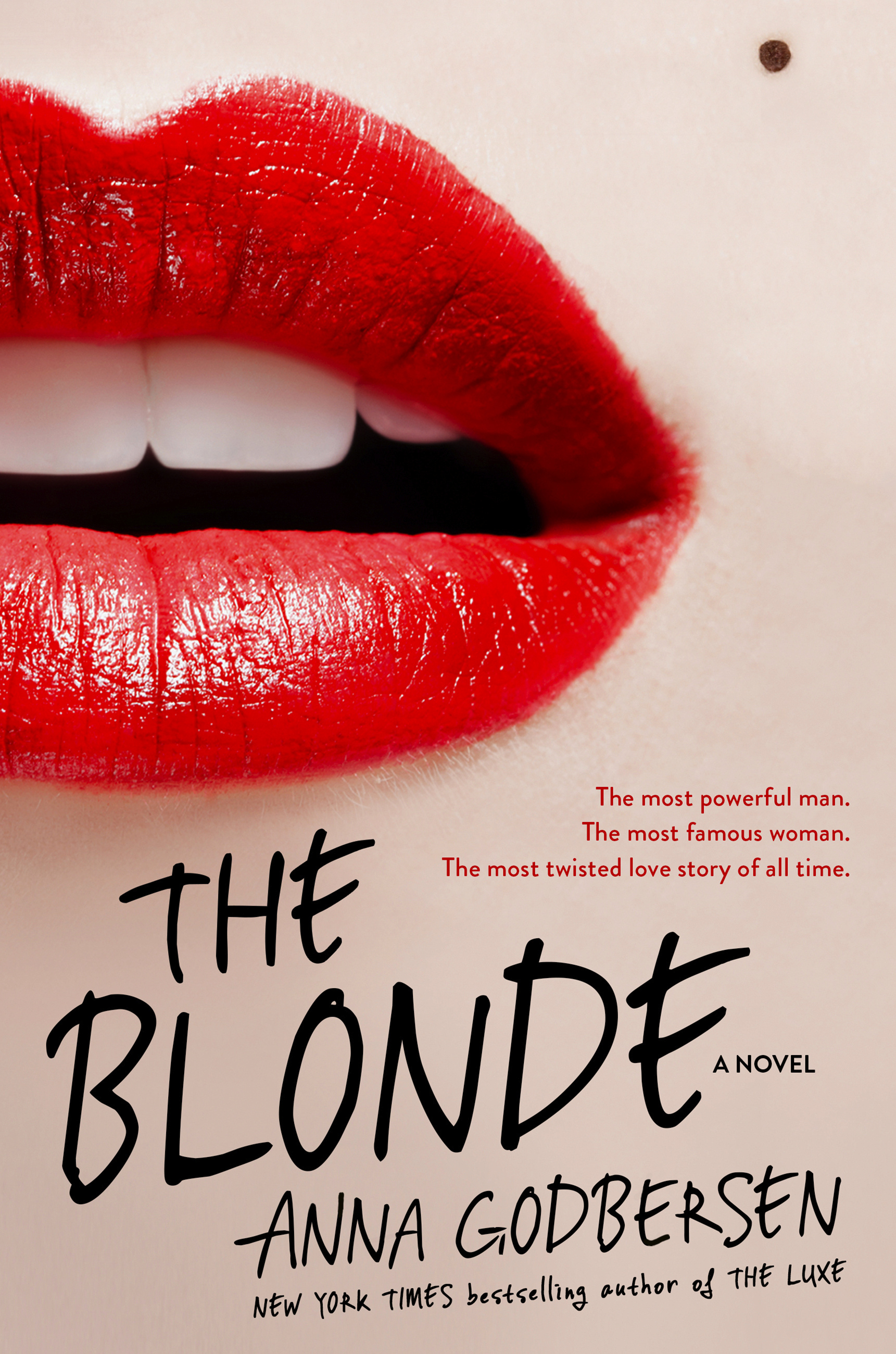

The Blonde

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$16.00Price

$19.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $16.00 $19.99 CAD

- ebook $10.99 $14.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around May 26, 2015. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

In 1947, a young, unknown Norma Jeane Baker meets a mysterious man in Los Angeles who transforms her into Marilyn Monroe, the star. Twelve years later he comes back for his repayment, and Marilyn is given her first assignment from the KGB: uncover something about JFK that no one else knows.

But a simple job turns complicated when Marilyn falls in love with the bright young President, and learns of plans to assassinate Kennedy. More than anything, Marilyn wants to escape her Soviet handlers and save her love — and herself. Desperate, ruthless and brilliant, what she does next will leave readers reeling.

From New York Times bestselling author Anna Godbersen comes a whip-smart re-imagining of the life of Marilyn Monroe, set in a world of silver screen glamour and political intrigue. At once a crackling portrayal of Old Hollywood, an intimate portrait of the larger-than-life star, and a cat-and-mouse thriller, The Blonde is history rewritten as it could have — and might have been.

Genre:

- On Sale

- May 26, 2015

- Page Count

- 400 pages

- Publisher

- Hachette Books

- ISBN-13

- 9781602862814

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use