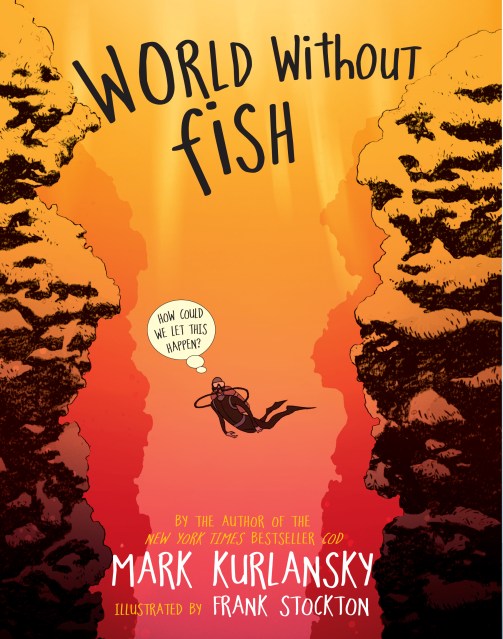

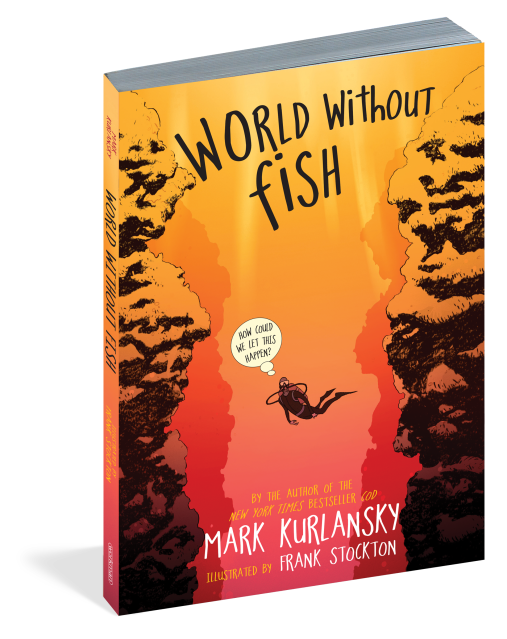

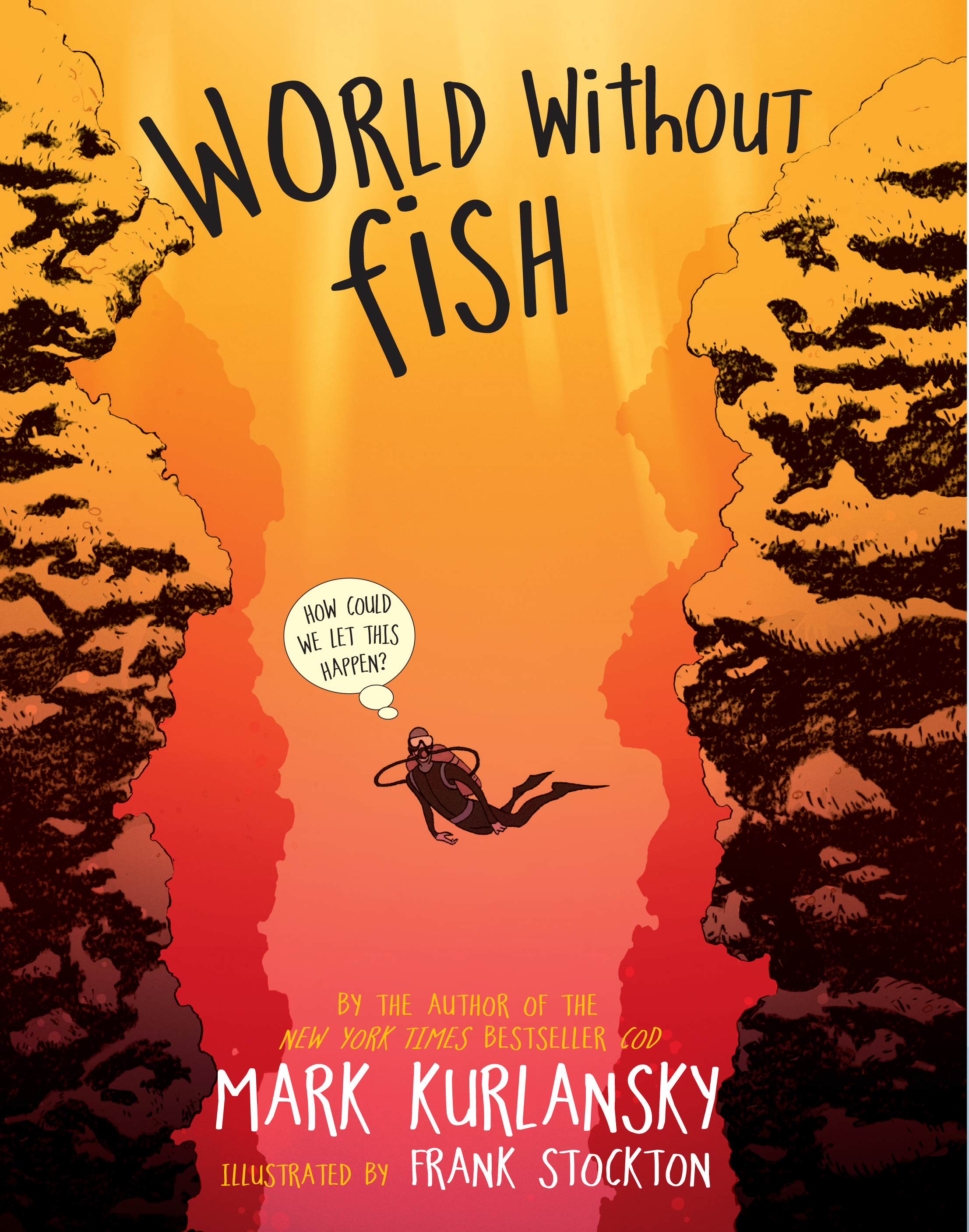

World Without Fish

Contributors

Illustrated by Frank Stockton

Formats and Prices

Price

$16.99Price

$22.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $16.99 $22.99 CAD

- ebook $10.99 $13.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around November 4, 2014. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

A KID’S GUIDE TO THE OCEAN

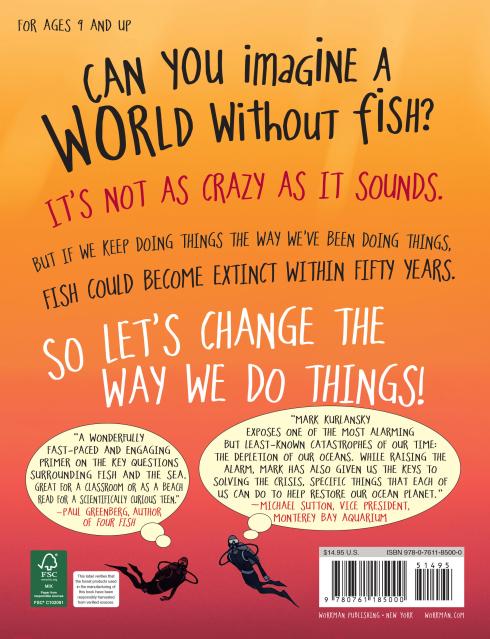

"Can you imagine a world without fish? It's not as crazy as it sounds. But if we keep doing things the way we've been doing things, fish could become extinct within fifty years. So let's change the way we do things!"

World Without Fish is the uniquely illustrated narrative nonfiction account—for kids—of what is happening to the world’s oceans and what they can do about it. Written by Mark Kurlansky, author of Cod, Salt, The Big Oyster, and many other books, World Without Fish has been praised as “urgent” (Publishers Weekly) and “a wonderfully fast-paced and engaging primer on the key questions surrounding fish and the sea” (Paul Greenberg, author of Four Fish). It has also been included in the New York State Expeditionary Learning English Language Arts Curriculum.

Written by a master storyteller, World Without Fish connects all the dots—biology, economics, evolution, politics, climate, history, culture, food, and nutrition—in a way that kids can really understand. It describes how the fish we most commonly eat, including tuna, salmon, cod, swordfish—even anchovies— could disappear within fifty years, and the domino effect it would have: the oceans teeming with jellyfish and turning pinkish orange from algal blooms, the seabirds disappearing, then reptiles, then mammals. It describes the back-and-forth dynamic of fishermen, who are the original environmentalists, and scientists, who not that long ago considered fish an endless resource. It explains why fish farming is not the answer—and why sustainable fishing is, and how to help return the oceans to their natural ecological balance.

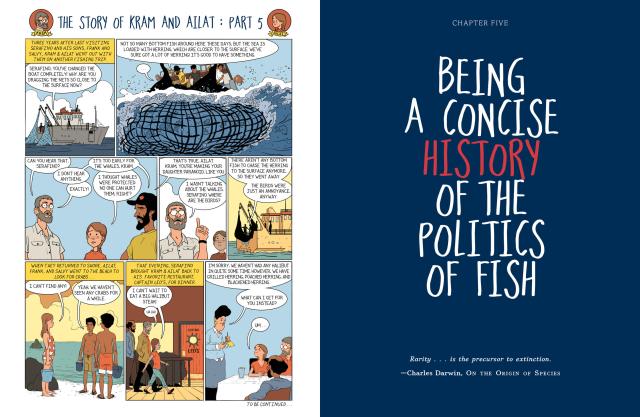

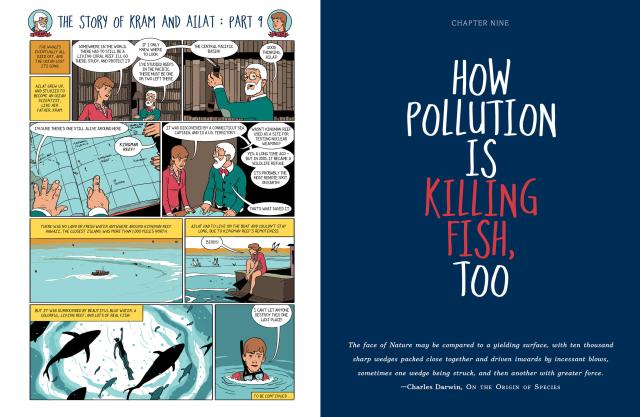

Interwoven with the book is a twelve-page graphic novel. Each beautifully illustrated chapter opener links to the next to form a larger fictional story that perfectly complements the text.

"Can you imagine a world without fish? It's not as crazy as it sounds. But if we keep doing things the way we've been doing things, fish could become extinct within fifty years. So let's change the way we do things!"

World Without Fish is the uniquely illustrated narrative nonfiction account—for kids—of what is happening to the world’s oceans and what they can do about it. Written by Mark Kurlansky, author of Cod, Salt, The Big Oyster, and many other books, World Without Fish has been praised as “urgent” (Publishers Weekly) and “a wonderfully fast-paced and engaging primer on the key questions surrounding fish and the sea” (Paul Greenberg, author of Four Fish). It has also been included in the New York State Expeditionary Learning English Language Arts Curriculum.

Written by a master storyteller, World Without Fish connects all the dots—biology, economics, evolution, politics, climate, history, culture, food, and nutrition—in a way that kids can really understand. It describes how the fish we most commonly eat, including tuna, salmon, cod, swordfish—even anchovies— could disappear within fifty years, and the domino effect it would have: the oceans teeming with jellyfish and turning pinkish orange from algal blooms, the seabirds disappearing, then reptiles, then mammals. It describes the back-and-forth dynamic of fishermen, who are the original environmentalists, and scientists, who not that long ago considered fish an endless resource. It explains why fish farming is not the answer—and why sustainable fishing is, and how to help return the oceans to their natural ecological balance.

Interwoven with the book is a twelve-page graphic novel. Each beautifully illustrated chapter opener links to the next to form a larger fictional story that perfectly complements the text.

-

“In his histories of cod and oysters, Mark Kurlansky described how those species once thrived in the wild, and how they were depleted. [World Without Fish] casts an even wider net and, with the help of superb illustrations and an interwoven graphic novel by Frank Stockton, creates a compelling narrative for young people.”The New York Times

—The New York Times

- On Sale

- Nov 4, 2014

- Page Count

- 208 pages

- Publisher

- Workman Publishing Company

- ISBN-13

- 9780761185000

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use