Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

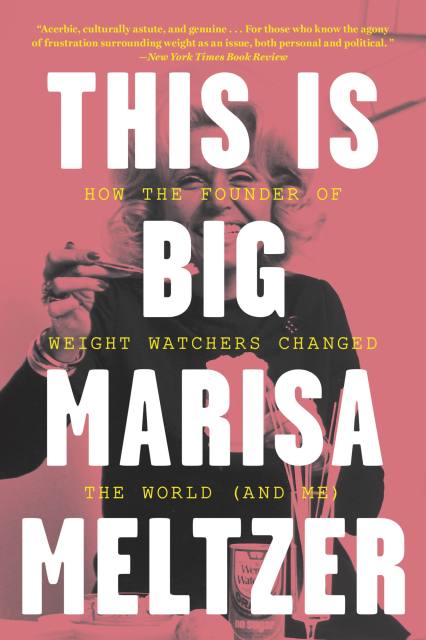

This Is Big

How the Founder of Weight Watchers Changed the World -- and Me

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Apr 14, 2020

- Page Count

- 7 pages

- Publisher

- Little, Brown and Company

- ISBN-13

- 9780316413992

Price

$11.99Price

$15.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $11.99 $15.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

- Trade Paperback $21.99 $28.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around April 14, 2020. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

From a contributor to The Cut, one of Vogue's most anticipated books "bravely and honestly" (Busy Philipps) talks about weight loss and sheds a light on Weight Watchers founder Jean Nidetch: "a triumphant chronicle" (New York Times).

Marisa Meltzer began her first diet at the age of five. Growing up an indoors-loving child in Northern California, she learned from an early age that weight was the one part of her life she could neither change nor even really understand.

Fast forward nearly four decades. Marisa, also a contributor to the New Yorker and the New York Times, comes across an obituary for Jean Nidetch, the Queens, New York housewife who founded Weight Watchers in 1963. Weaving Jean's incredible story as weight loss maven and pathbreaking entrepreneur with Marisa's own journey through Weight Watchers, she chronicles the deep parallels, and enduring frustrations, in each woman's decades-long efforts to lose weight and keep it off. The result is funny, unexpected, and unforgettable: a testament to how transformation goes far beyond a number on the scale.

Marisa Meltzer began her first diet at the age of five. Growing up an indoors-loving child in Northern California, she learned from an early age that weight was the one part of her life she could neither change nor even really understand.

Fast forward nearly four decades. Marisa, also a contributor to the New Yorker and the New York Times, comes across an obituary for Jean Nidetch, the Queens, New York housewife who founded Weight Watchers in 1963. Weaving Jean's incredible story as weight loss maven and pathbreaking entrepreneur with Marisa's own journey through Weight Watchers, she chronicles the deep parallels, and enduring frustrations, in each woman's decades-long efforts to lose weight and keep it off. The result is funny, unexpected, and unforgettable: a testament to how transformation goes far beyond a number on the scale.

-

Named a Best Book of the Year by

Glamour

Esquire

Real Simple

-

“In this memoir-nonfiction hybrid, Meltzer skillfully blends her own extensive dieting history with the life story of Jean Nidetch, the Queens housewife who founded Weight Watchers in 1963 and helped to create “diet culture” as we know it today.” VogueVogue

-

"Her life changed dramatically as she realized you can live a big life at any size."People

-

"A triumphant chronicle... Meltzer has created singular companionate text for those who know the agony of frustration surrounding weight as an issue, both personal and political. Acerbic, culturally astute and genuine, [Meltzer] makes exquisite company in the struggle."New York Times

-

"Meltzer writes movingly of her own struggles with having a body, but her experiment isn't the exclusive focus of the book: It also chronicles the life of Weight Watchers founder Jean Nidetch, whose vaudevillian comic timing, retrograde ideas about fat and happiness, and unconcealed desire for fame and connection make her a fascinating subject."Vox

-

"Marisa Meltzer's new Weight Watchers biography feels surprisingly in sync with the emotional arc of isolation eating."Wall Street Journal Magazine

-

"If you've ever been critical of diets, diet companies, and diet culture in the past, you're going to love what Meltzer has to offer here."Bustle

-

"Not a memoir of radical self-acceptance or saccharine inspiration, but a candid - at times dark - look at what it means to be an overweight woman in 2020."Los Angeles Times

-

"This heartfelt, incisive book layers the story of Weight Watchers founder Jean Nidetch with the author's own lifelong journey through various fad diets. What emerges is a surprising portrait of a remarkable but little-known life in business, as well as a thoughtful critique of America's obsession with thinness."Esquire

-

"This is Big...[finds] in Nidetch both a genuine pioneer - a woman who built a massive culture-defining business as a time when women couldn't even have their own credit cards - and a representative of many ideas about weight and health that are as destructive as they are enduring."Vanity Fair

-

"Meltzer looks at her own pursuit of weight loss and uses it to illuminate our culture's relentless focus on thinness."Washington Post

-

"[This] brilliant book tells the story of thinness obsession through the lives of two women-Jean Nidetch, the founder of Weight Watchers, and Meltzer herself."Glamour

-

"Meltzer looks at her own pursuit of weight loss and uses it to illuminate our culture's relentless focus on thinness."The Daily Beast

-

"Inventive...Meltzer's own experience with weight loss."Bitch

-

"This book is an honest, open exploration of one woman's relationship with her body as it exists in the world."Here Magazine

-

"[Meltzer] writes with a voice that feels like you're chatting with one of your best friends, cracking jokes and digging into all the emotions you'd usually hide from others who aren't as close to you."First for Women

-

"Journalist Marisa Meltzer interweaves her personal dieting history with a compelling biography of Jean Nidetch, the woman who founded Weight Watchers. As the author chronicles her own journey through the popular program, she describes how Nidetch-despite getting and staying thin-struggled at home and at work. In the end, Meltzer learns and grows in unexpected ways."Real Simple

-

"The cleverly told story of both Jean Nidetch, founder of Weight Watchers, and Meltzer's own lifelong battle with her body and her weight."Kim France, Girls of a Certain Age

-

"Meltzer did a deep dive into Jean Nidetch, the Queens, NY, housewife who founded Weight Watchers in 1963, for a book that is part biography, part memoir of her own lifelong journey with dieting."New York Post

-

"Her story will resonate with readers who have struggled with weight and body image issues. A straightforward memoir of struggling with obesity and finding inspiration from the founder of Weight Watchers."Kirkus

-

"Meltzer's engaging history of Weight Watchers and candid account of her own dieting journey is a frank and affirming portrait of the ways women, in particular, have always coped with health and self image."Booklist

-

"Insightful...a thoughtful exploration of how to make diet choices on one's own terms."Publishers Weekly

-

"This is Big is a brave, bold, funny, honest, riveting book that made me have every kind of feeling in the world."Jami Attenberg, author of All Grown Up

-

"For anyone who has ever felt defeated by food, betrayed by their own body, embarrassed for not only lacking the willpower to change their habits but also embarrassed by the desire to change their own body, Marisa Meltzer sees you, has written this book for you because she is you. While simultaneously delving into the history of the woman who started Weight Watchers and bravely and honestly examining her own complicated relationship with food and weight, Marisa has written a book that perfectly captures our country's obsession with THIN and the struggle with obesity at this moment in history."Busy Philipps, author of This Will Only Hurt A Little

-

"Marisa Meltzer is an ingenious writer. This Is Big expertly weaves together two engaging tales: the charming, funny, and often heartbreaking account of Meltzer's lifelong attempts at bodily transformation, and the little-known story of a largely forgotten American icon Jean Nidetch, the irrepressible, pathbreaking entrepreneur who founded the now billion-dollar company Weight Watchers in her modest living room in 1963."Nancy Jo Sales, author of American Girls and The Bling Ring

-

"This book was so good that I devoured it (with no guilt)! Meltzer shows us, through honesty, rawness and deep vulnerability, the complexities of living in a body that doesn't adhere to society's narrow beauty standards in an era that holds up body positivity as gospel."Mara Altman, author of Gross Anatomy

-

"A witty and meaningful look at our obsession with weight and dieting; blending the story of the founder of Weight Watchers with her own saga, Marisa Meltzer crafts an amusing story with universal insights.''SheilaWeller, author of Girls Like Us: Carole King, Joni Mitchell, Carly Simon -and the Journey of a Generation and Carrie Fisher; A Life On The Edge

-

"This book is an incredible hybrid: both a detailed study of an extraordinary American life, and a candid and revealing memoir. Meltzer is the biographer Jean Nidetech deserves, crafting a portrait of the woman and the world in which she lived. She's also a bracing memoirist, a warm and honest voice unafraid to offer readers the stuff of her own life to help us better understand the culture we now share. It's a remarkable feat."Rumaan Alam, author of That Kind of Mother and Rich and Pretty