Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

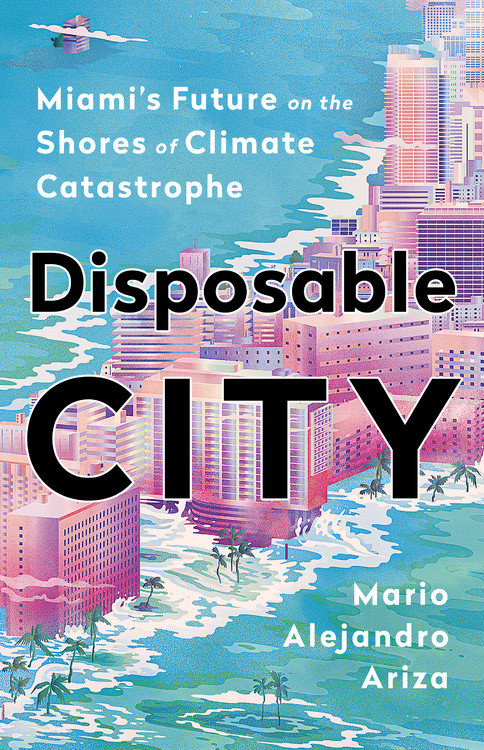

Disposable City

Miami's Future on the Shores of Climate Catastrophe

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$28.00Price

$35.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $28.00 $35.00 CAD

- ebook $17.99 $22.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around July 14, 2020. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

A deeply reported personal investigation by a Miami journalist examines the present and future effects of climate change in the Magic City — a watery harbinger for coastal cities worldwide.

In Disposable City, Miami resident Mario Alejandro Ariza shows us not only what climate change looks like on the ground today, but also what Miami will look like 100 years from now, and how that future has been shaped by the city’s racist past and present. As politicians continue to kick the can down the road and Miami becomes increasingly unlivable, real estate vultures and wealthy residents will be able to get out or move to higher ground, but the most vulnerable communities, disproportionately composed of people of color, will face flood damage, rising housing costs, dangerously higher temperatures, and stronger hurricanes that they can’t afford to escape.

Miami may be on the front lines of climate change, but the battle it’s fighting today is coming for the rest of the U.S. — and the rest of the world — far sooner than we could have imagined even a decade ago. Disposable City is a thoughtful portrait of both a vibrant city with a unique culture and the social, economic, and psychic costs of climate change that call us to act before it’s too late.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Jul 14, 2020

- Page Count

- 320 pages

- Publisher

- Bold Type Books

- ISBN-13

- 9781541788466

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use