Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

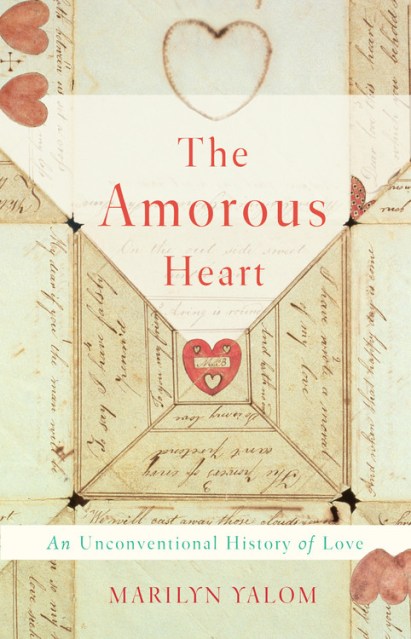

The Amorous Heart

An Unconventional History of Love

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$27.00Price

$35.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover (Unabridged) $27.00 $35.00 CAD

- ebook $16.99 $21.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around January 9, 2018. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

The symmetrical, exuberant heart is everywhere: it gives shape to candy, pendants, the frothy milk on top of a cappuccino, and much else. How can we explain the ubiquity of what might be the most recognizable symbol in the world?

In The Amorous Heart, Marilyn Yalom tracks the heart metaphor and heart iconography across two thousand years, through Christian theology, pagan love poetry, medieval painting, Shakespearean drama, Enlightenment science, and into the present. She argues that the symbol reveals a tension between love as romantic and sexual on the one hand, and as religious and spiritual on the other. Ultimately, the heart symbol is a guide to the astonishing variety of human affections, from the erotic to the chaste and from the unrequited to the conjugal.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Jan 9, 2018

- Page Count

- 288 pages

- Publisher

- Basic Books

- ISBN-13

- 9780465094707

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use