By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

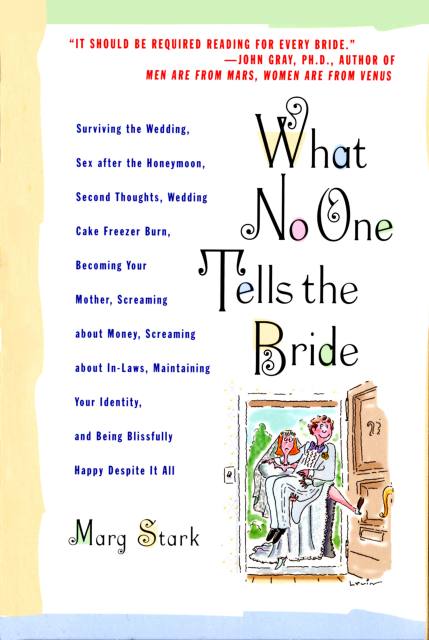

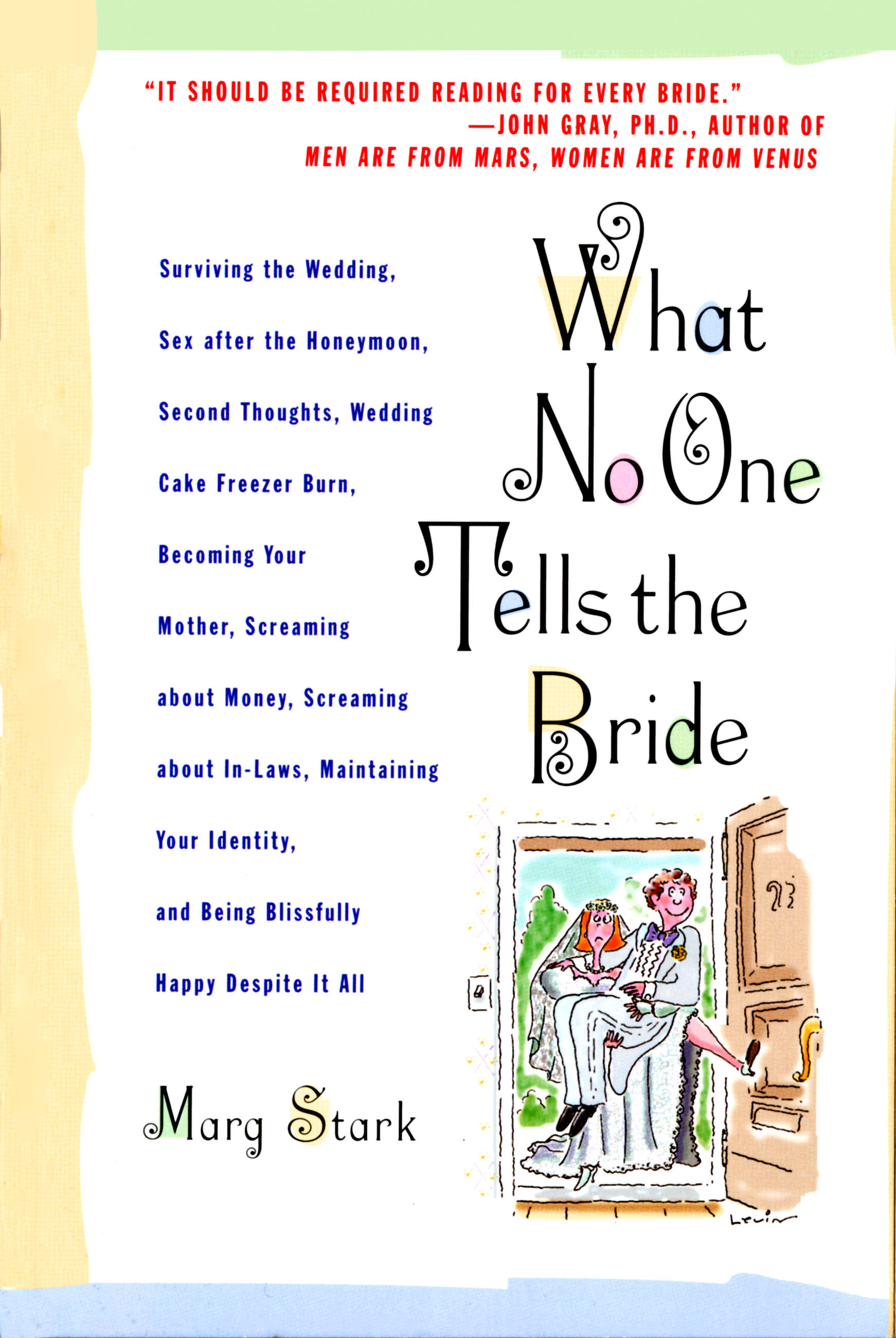

What No One Tells the Bride

Surviving the Wedding, Sex After the Honeymoon, Second Thoughts, Wedding Cake Freezer Burn, Becoming Your Mother, Screaming about Money, Screaming about In-Laws, Maintaining Your Identity, and Being Blissfully Happy Despite It All

Contributors

By Marg Stark

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Aug 13, 2013

- Page Count

- 320 pages

- Publisher

- Grand Central Publishing

- ISBN-13

- 9781401306076

Price

$9.99Price

$12.99 CADFormat

Format:

ebook $9.99 $12.99 CADThis item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around August 13, 2013. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

- You don’t feel like a “Mrs.” Sometimes you even dream about old boyfriends.

- You write all the wedding gift thank-you notes. So you are doomed to your mother’s life–60 years of doing more than your share?

- Making love is the last thing on your mind when you have the flu and haven’t showered for days. But he still wants to.

- You tell him you got these incredible bargains and quietly resent having to justify your spending.

- You have shining moments when marriage feels absolutely right, but nevertheless you pine for something more.

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use