Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

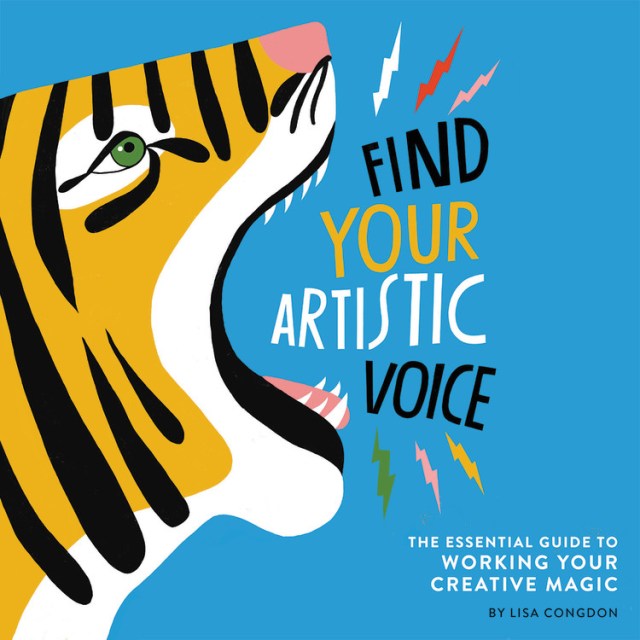

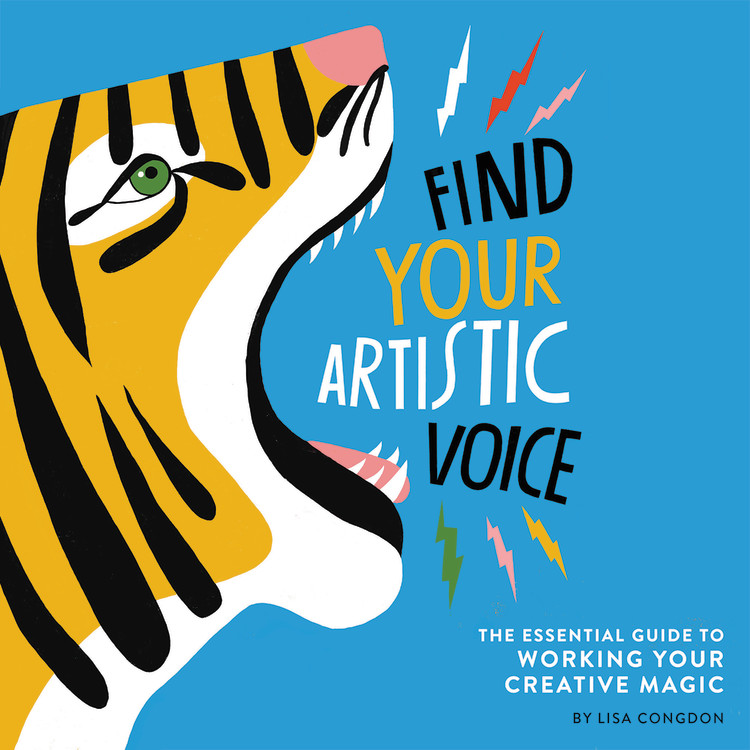

Find Your Artistic Voice

The Essential Guide to Working Your Creative Magic

Contributors

By Lisa Congdon

Read by Lisa Congdon

Formats and Prices

Format

Format:

Audiobook Download (Unabridged)This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around August 6, 2019. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

Find Your Artistic Voice helps artists and creatives identify and nurture their own visual identity.

This one-of-a-kind book helps artists navigate the influence of creators they admire, while simultaneously appreciating the value of their personal journey.

• Features down-to-earth and encouraging advice from Congdon herself

• Filled with interviews with established artists, illustrators, and creatives

• Answers the question how do I develop a unique artistic style?”

An artist’s voice is their calling card—it’s what makes each of their works vital and particular

Genre:

- On Sale

- Aug 6, 2019

- Publisher

- Chronicle Books

- ISBN-13

- 9781797200026

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use