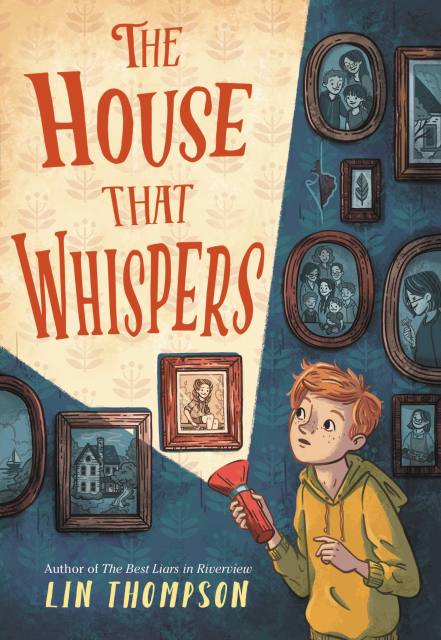

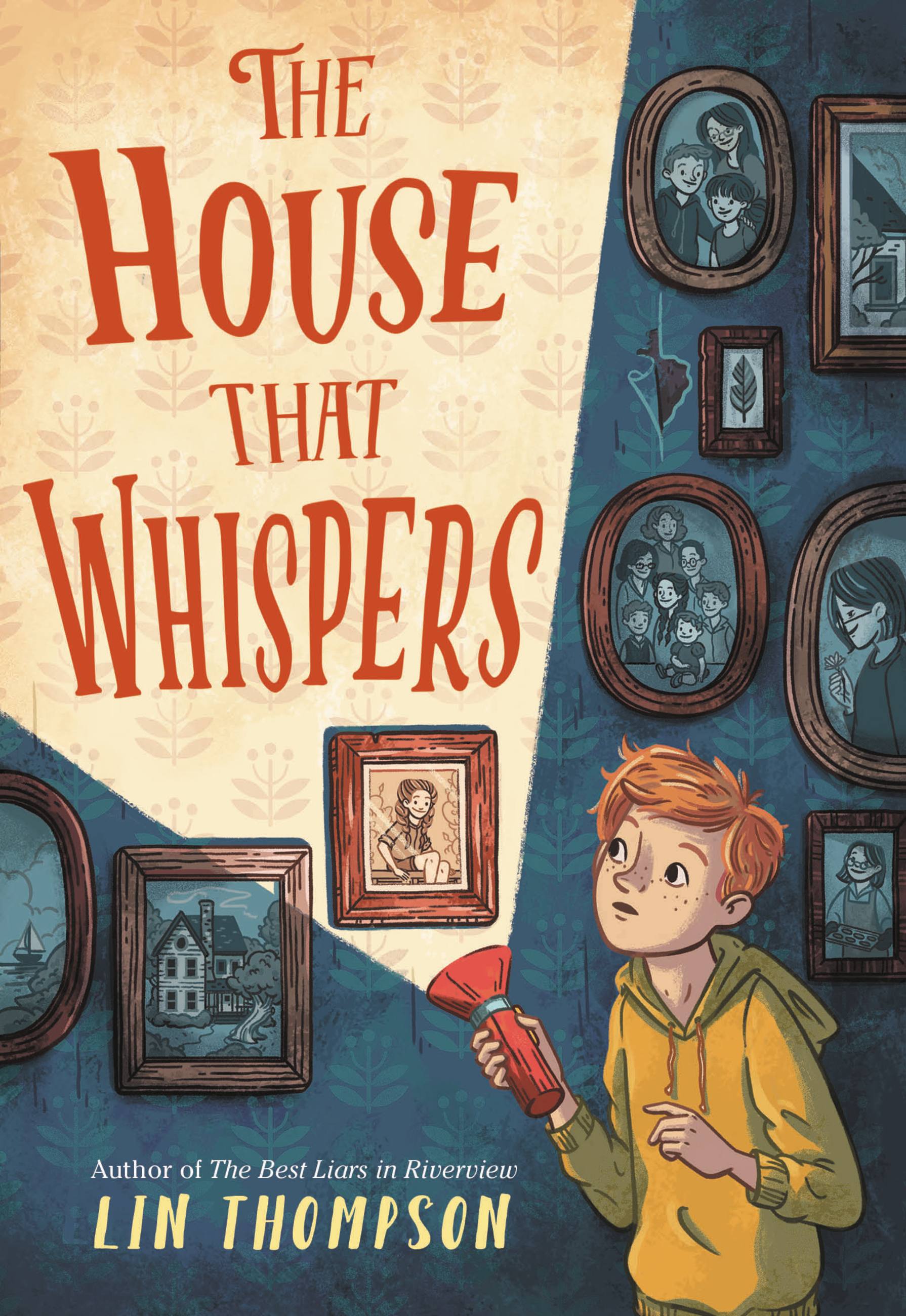

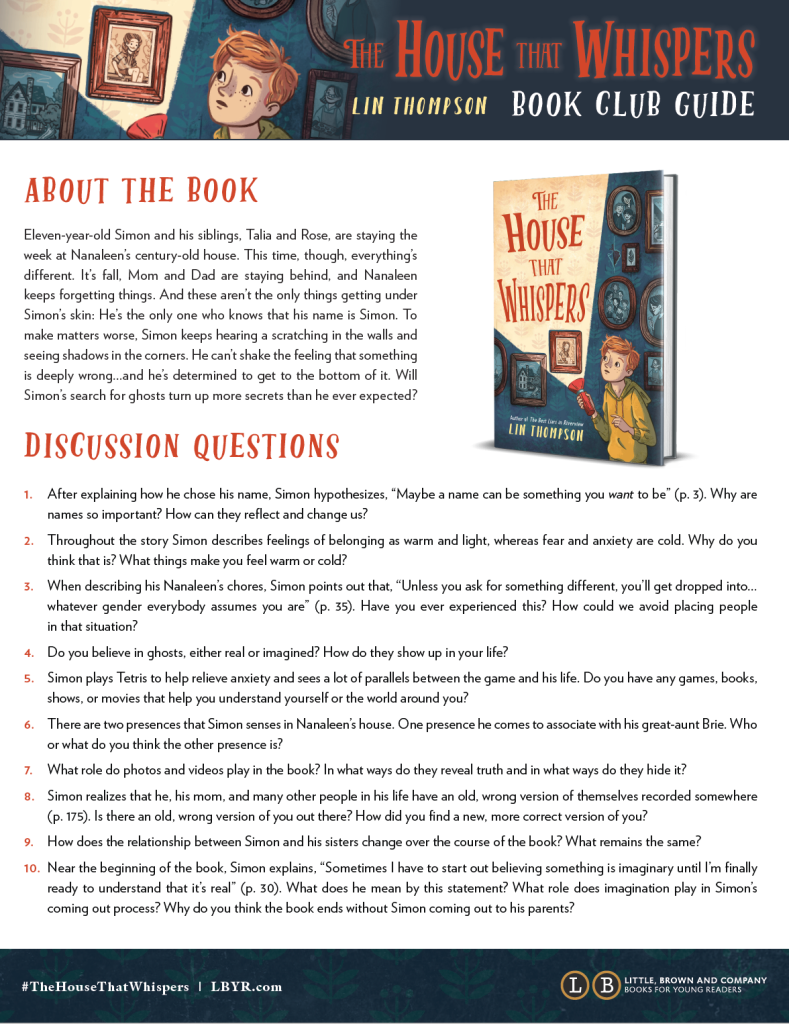

The House That Whispers

Contributors

By Lin Thompson

Formats and Prices

Price

$16.99Price

$22.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $16.99 $22.99 CAD

- ebook $9.99 $12.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around February 28, 2023. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

Eleven-year-old Simon and his siblings, Talia and Rose, are staying the week at Nanaleen's century-old house. This time, though, it’s not their usual summer vacation trip. In fact, everything’s different. It’s fall, not summer. Mom and Dad are staying behind to have a “talk.” And Nanaleen’s house smells weird, plus she keeps forgetting things. And these aren’t the only things getting under Simon’s skin: He’s the only one who knows that his name is Simon, and that he and him pronouns are starting to feel right. But he’s not ready to add to the changes that are already in motion in his family.

To make matters worse, Simon keeps hearing a scratching in the walls, and shadows are beginning to build in the corners. He can’t shake the feeling that something is deeply wrong…and he’s determined to get to the bottom of it—which means launching a ghost hunt, with or without his sisters’ help. When Simon discovers the hidden story of his great-aunt Brie, he realizes that Brie’s life might hold answers to some of his worries. Is Brie’s ghost haunting the old O’Hagan house? And will Simon’s search for ghosts turn up more secrets than he ever expected?

-

"Thompson (The Best Liars in Riverview) punctuates a gentle story of bonding with genuinely scary moments and lovely descriptions of gender euphoria.... Reminiscent of Kyle Lukoff’s Too Bright to See, it’s an intriguing, warmhearted exploration of beauty and change."Publishers Weekly

-

"Readers exploring their own gender identities will find a friend in Simon, who knows who he is but is adamant that it’s nobody else’s business and that if/when you come out, it is something you choose, not something you owe anyone. Highly recommended for fans of Kyle Lukoff."Booklist

-

"Thompson’s sophomore novel is a blend of mystery, light horror, and a coming-of-age tale.... Recommended for purchase where there is high demand for stories focused on identity for younger readers."School Library Journal

-

Praise for The Best Liars in Riverview:

* “Thompson’s debut is a heartfelt coming-of-age journey that explores identity, friendship, and learning to accept who you are, even if you don’t quite understand it yet.” —Booklist, starred review

“The Best Liars in Riverview is a beautiful and heartwarming exploration of self-discovery. Lin Thompson writes with love and respect for their readers, and I’m excited for the young people who will have the chance to read their story. A stunning and potentially life-changing, life-saving debut.” —Kacen Callender, National Book Award-winning author of King and the Dragonflies

"The Best Liars in Riverview is a lyrically told tale about friendship, found family, belonging and hope. Thompson has crafted a gorgeous debut that will fill an important place on LGBTQ+ shelves, and Aubrey is a character that will stay with me for a long time." —Nicole Melleby, author of Hurricane Season

"A beautifully written, nuanced exploration of identity, The Best Liars in Riverview is heartbreaking at times in the truths it reveals about growing up and feeling different in a rural community. It also offers so much comfort and hope. Thompson's debut is a lyrical, wonderfully queer story that will forever hold a special place in my heart." —A. J. Sass, author of Ana on the Edge and Ellen Outside the Lines

"Tender and bold all at once, Thompson's breathtaking debut about found family and identity will infuse readers hope and courage. A luminous read." —Ashley Herring Blake, Stonewall honor winner of Ivy Aberdeen's Letter to the World

“Don’t let the title fool you. Achingly honest and deeply moving, The Best Liars in Riverview empowers readers to seek their own truth—and live it.” —Lisa Jenn Bigelow, author of the Lambda Literary Award book, Hazel’s Theory of Evolution

“A dazzlingly atmospheric debut about truth-telling made possible through found family and self-discovery. Lin Thompson writes with heartfelt incisiveness about the pain of alienation, the preciousness of friendship, and the empowerment that comes through being seen and believed. Aubrey left an indelible mark on my heart, and their riveting story will encourage young readers everywhere to “say something” when the time is right.” —Kathryn Ormsbee, author of The House in Poplar Wood

“A sensitively written first novel…this heartfelt story shows rather than tells how friendship can lead to understanding.” —Publishers Weekly

"A gentle and genuine coming-out story." —Kirkus Reviews

“Thompson’s tale will have readers guessing up until the very end. A gratifying middle grade read for students who enjoy tales of adventure and belonging.” —School Library Journal

- On Sale

- Feb 28, 2023

- Page Count

- 336 pages

- Publisher

- Little, Brown Books for Young Readers

- ISBN-13

- 9780316277112

Praise

-

"Thompson (The Best Liars in Riverview) punctuates a gentle story of bonding with genuinely scary moments and lovely descriptions of gender euphoria…. Reminiscent of Kyle Lukoff’s Too Bright to See, it’s an intriguing, warmhearted exploration of beauty and change."Publishers Weekly

-

"Readers exploring their own gender identities will find a friend in Simon, who knows who he is but is adamant that it’s nobody else’s business and that if/when you come out, it is something you choose, not something you owe anyone. Highly recommended for fans of Kyle Lukoff."Booklist

-

"Thompson’s sophomore novel is a blend of mystery, light horror, and a coming-of-age tale…. Recommended for purchase where there is high demand for stories focused on identity for younger readers."School Library Journal

-

Praise for The Best Liars in Riverview:

* “Thompson’s debut is a heartfelt coming-of-age journey that explores identity, friendship, and learning to accept who you are, even if you don’t quite understand it yet.” —Booklist, starred review

“The Best Liars in Riverview is a beautiful and heartwarming exploration of self-discovery. Lin Thompson writes with love and respect for their readers, and I’m excited for the young people who will have the chance to read their story. A stunning and potentially life-changing, life-saving debut.” —Kacen Callender, National Book Award-winning author of King and the Dragonflies

"The Best Liars in Riverview is a lyrically told tale about friendship, found family, belonging and hope. Thompson has crafted a gorgeous debut that will fill an important place on LGBTQ+ shelves, and Aubrey is a character that will stay with me for a long time." —Nicole Melleby, author of Hurricane Season

"A beautifully written, nuanced exploration of identity, The Best Liars in Riverview is heartbreaking at times in the truths it reveals about growing up and feeling different in a rural community. It also offers so much comfort and hope. Thompson's debut is a lyrical, wonderfully queer story that will forever hold a special place in my heart." —A. J. Sass, author of Ana on the Edge and Ellen Outside the Lines

"Tender and bold all at once, Thompson's breathtaking debut about found family and identity will infuse readers hope and courage. A luminous read." —Ashley Herring Blake, Stonewall honor winner of Ivy Aberdeen's Letter to the World

“Don’t let the title fool you. Achingly honest and deeply moving, The Best Liars in Riverview empowers readers to seek their own truth—and live it.” —Lisa Jenn Bigelow, author of the Lambda Literary Award book, Hazel’s Theory of Evolution

“A dazzlingly atmospheric debut about truth-telling made possible through found family and self-discovery. Lin Thompson writes with heartfelt incisiveness about the pain of alienation, the preciousness of friendship, and the empowerment that comes through being seen and believed. Aubrey left an indelible mark on my heart, and their riveting story will encourage young readers everywhere to “say something” when the time is right.” —Kathryn Ormsbee, author of The House in Poplar Wood

“A sensitively written first novel…this heartfelt story shows rather than tells how friendship can lead to understanding.” —Publishers Weekly

"A gentle and genuine coming-out story." —Kirkus Reviews

“Thompson’s tale will have readers guessing up until the very end. A gratifying middle grade read for students who enjoy tales of adventure and belonging.” —School Library Journal