Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

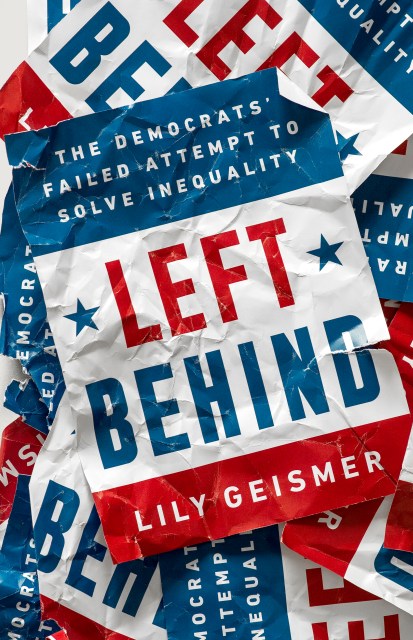

Left Behind

The Democrats' Failed Attempt to Solve Inequality

Contributors

By Lily Geismer

Formats and Prices

Price

$17.99Price

$22.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $17.99 $22.99 CAD

- Hardcover $30.00 $38.00 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $31.99

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around March 1, 2022. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

The 40-year history of how Democrats chose political opportunity over addressing inequality—and how the poor have paid the price

For decades, the Republican Party has been known as the party of the rich: arguing for “business-friendly” policies like deregulation and tax cuts. But this incisive political history shows that the current inequality crisis was also enabled by a Democratic Party that catered to the affluent.

The result is one of the great missed opportunities in political history: a moment when we had the chance to change the lives of future generations and were too short-sighted to take it.

Historian Lily Geismer recounts how the Clinton-era Democratic Party sought to curb poverty through economic growth and individual responsibility rather than asking the rich to make any sacrifices. Fueled by an ethos of “doing well by doing good,” microfinance, charter schools, and privately funded housing developments grew trendy. Though politically expedient and sometimes profitable in the short term, these programs fundamentally weakened the safety net for the poor.

This piercingly intelligent book shows how bygone policy decisions have left us with skyrocketing income inequality and poverty in America and widened fractures within the Democratic Party that persist to this day.

Genre:

-

“Left Behind lucidly conveys how the Clintonian ‘New Democrats’ of the 1990s looked to beat Republicans with market-based policies, but in the end contributed to traumatic losses for all too many and a steep decline in public trust. The struggle underway for the soul of the Democratic Party seems all the more urgent in light of this bracing reassessment.”Nancy MacLean, author of Democracy in Chains and finalist for the National Book Award

-

“Left Behind is a powerful critique of a technocratic, market-driven approach to government that has never lived up to its promise. Geismer shows in painful detail how the Democratic Party of the recent past could have helped the poor—but chose not to fight for them. This is not just history—it’s a map that takes us, inexorably, to the mess we’re still in.”Stephanie Kelton, New York Times–bestselling author of The Deficit Myth

-

“Geismer’s outstanding Left Behind addresses a critical breach in our understanding of how the Democratic Party transformed from ‘big government’ liberalism to the champions of privatization. These policy choices have contributed to inequality and social instability, the impacts of which underlie the social unrest and disquietude that roils US society today. A crucial read.”Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor, author of Race for Profit and finalist for the 2020 Pulitzer Prize in History

-

“Tremendous. This book shows how the ideas of the Clinton-era Democrats emerged historically, setting them up for a clear and convincing debunking. We’re along for the ride with these characters as they become enamored of horrible ideas, with disastrous consequences. This book is an absolute must-read, especially for those who think they already know this story.”Chenjerai Kumanyika, assistant professor at Rutgers and cohost of the podcast Uncivil

-

“Left Behind should spur serious soul-searching among the American center-left. It is a book about well-intentioned policy not working out, but also about blasé indifference of policymakers as to whether their policies worked or not, and whether the point was for them to ‘work’ for the people affected by policy or for ideas to work in a speech.”The New Republic

-

“Geismer’s book is a wonderfully detailed history of a now-extinct faith.”New York Times Book Review

-

“Geismer deftly weaves politics with policy to show how the Democrats reimagined poverty as a market failure… Catnip for policy wonks and political junkies, offering solid lessons for Democrats going forward.”Kirkus

-

“Framing the story as a tragedy of good intentions gone wrong, Geismer transforms wonky policy matters into an unlikely page-turner. Readers will gain valuable insight into the Clinton presidency and its legacy in today’s distrust between progressives and centrist Democrats.”Publishers Weekly

-

“Lily Geismer’s impressive, readable new book on the history of the New Democrats.”Washington Monthly

-

“I found this book to be particularly captivating, often shedding light the origin of policy positions espoused by prominent Democratic leaders today.”The Cascadia Advocate

-

“Lily Geismer has performed a great service to America…”OB Rag

-

“[A] provocative examination of the Bill Clinton presidency, its political and intellectual roots, and its lasting impact.”Jacobin

-

“[A] detailed examination.”The Baffler

-

“Because it is a true intellectual history in this sense, it is more useful than other accounts, and also more respectful, without tempering its critique, because it takes these politicians and public intellectuals seriously on their own terms.”Democracy Journal

-

“This history of ideas is important, and the book does an excellent job of covering the policy transformation within the Democratic Party.”Choice

-

“Exciting…Left Behind convincingly shows that Democrats helped shape modern American politics rather than only being overwhelmed by the Right.”Public Books

- On Sale

- Mar 1, 2022

- Page Count

- 448 pages

- Publisher

- PublicAffairs

- ISBN-13

- 9781541756984

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use