By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

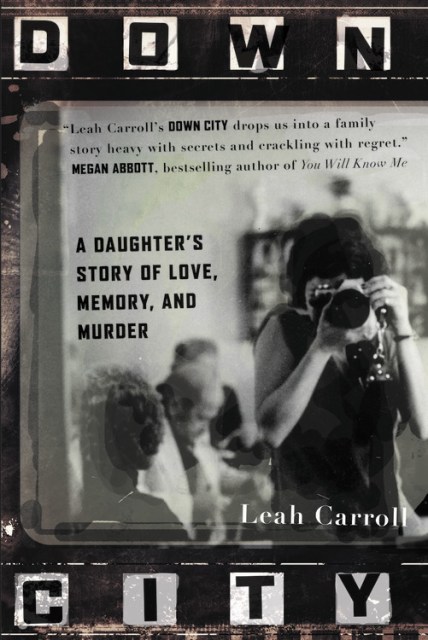

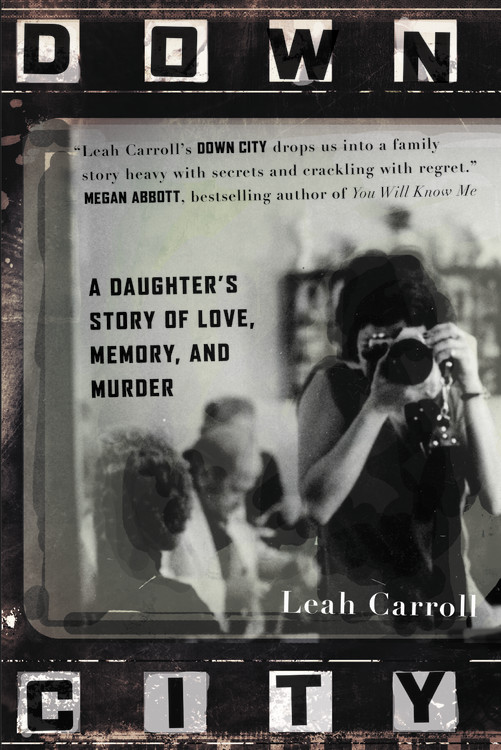

Down City

A Daughter's Story of Love, Memory, and Murder

Contributors

By Leah Carroll

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Mar 6, 2018

- Page Count

- 240 pages

- Publisher

- Grand Central Publishing

- ISBN-13

- 9781455563296

Price

$19.99Price

$25.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $19.99 $25.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around March 6, 2018. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Like James Ellroy’s, My Dark Places, Down City is a gripping narrative built of memory and reportage, and Leah Carroll’s portrait of Rhode Island is sure to take a place next Mary Karr’s portrayal of her childhood in East Texas and David Simon’s gritty Baltimore.

Leah Carroll’s mother, a gifted amateur photographer, was murdered by two drug dealers with Mafia connections when Leah was four years old. Her father, a charming alcoholic who hurtled between depression and mania, was dead by the time she was eighteen. Why did her mother have to die? Why did the man who killed her receive such a light sentence? What darkness did Leah inherit from her parents?

Leah was left to put together her own future and, now in her memoir, she explores the mystery of her parents’ lives, through interviews, photos, and police records. Down City is a raw, wrenching memoir of a broken family and an indelible portrait of Rhode Island- a tiny state where the ghosts of mafia kingpins live alongside the feisty, stubborn people working hard just to get by. Heartbreaking, and mesmerizing, it’s the story of a resilient young woman’s determination to discover the truth about a mother she never knew and the deeply troubled father who raised her-a man who was, Leah writes, “both my greatest champion and biggest obstacle.”

Leah Carroll’s mother, a gifted amateur photographer, was murdered by two drug dealers with Mafia connections when Leah was four years old. Her father, a charming alcoholic who hurtled between depression and mania, was dead by the time she was eighteen. Why did her mother have to die? Why did the man who killed her receive such a light sentence? What darkness did Leah inherit from her parents?

Leah was left to put together her own future and, now in her memoir, she explores the mystery of her parents’ lives, through interviews, photos, and police records. Down City is a raw, wrenching memoir of a broken family and an indelible portrait of Rhode Island- a tiny state where the ghosts of mafia kingpins live alongside the feisty, stubborn people working hard just to get by. Heartbreaking, and mesmerizing, it’s the story of a resilient young woman’s determination to discover the truth about a mother she never knew and the deeply troubled father who raised her-a man who was, Leah writes, “both my greatest champion and biggest obstacle.”

-

"Carroll proceeds from these haunting twin plot points [her parents' deaths] through a patchwork of vignettes, reportage and reflection that reaches after her absent parents with sensitive longing.... Carroll's writing is most evocative when she describes, with a heartbreaking mixture of tenderness and disappointment, the moments of intimate connection between her and her father."New York Times Book Review

-

"Leah Carroll's DOWN CITY drops us into a family story heavy with secrets and crackling with regret. Hers is a portrait of two parents straining desperately to find their better angels, and a daughter whose resilience is tested again and again. The fact that she proves herself both survivor and frank and generous curator of their story is a great gift, both to their memory and to readers alike."Megan Abbott, bestselling author of The Fever and You Will Know Me

-

"Carroll grasps fleeting moments and memories with confidence and disarming delicacy....So rich in mood, feeling, and genuine love, this investigative memoir is a true tribute."Booklist (starred review)

-

"Leah Carroll's writing is vivid and honest, and DOWN CITY is a clear-eyed act of regaining a father by artfully cataloging his loss."Charles Graeber, New York Times bestselling author of The Good Nurse: A True Story of Medicine, Madness, and Murder

-

"Quick and clear as glass, evocative and engaging, DOWN CITY is a story of a daughter's moving search for the truth about the parents whose dark complexities have left a mystery at the center of her existence."George Hodgman, author of Bettyville

-

"Leah Carroll's Rhode Island is seedy, charismatic, broke-down, and irresistible: so much like the characters in her gripping heartbreak of a memoir. Only a writer as brave in her heart as she is on the page could make us love the ghosts she chases through police reports, memory, and the desolate landmarks of her own tragedy. Leah Carroll is that writer, proving that no matter who haunts you or for how long, only forgiveness can set you free."Melissa Febos, author of Whip Smart and Abandon Me

-

"Raw and crushing . . . a thoroughly reported, deeply personal memoir."The Village Voice

-

"Crushing to read and intensely readable."The Wall Street Journal

-

"Driven by a ferocious demand for justice, Leah Carroll takes us with her as she extricates herself from layer after layer of lies, determined not only to find but to understand the truth about her parents' tragic lives. DOWN CITY is a riveting and heartbreaking inquiry, born of inner necessity, and written in a deceptively simple and deeply affecting prose that elevates its storytelling to art."Richard Hoffman, author of Half the House and Love & Fury

-

"Carroll's understated prose complements this daunting material, and her struggles as an unhappy, rebellious teen seem almost idyllic in contrast to the dysfunction and tragedy that shadow her... Carroll's determined grappling with the burden of her past is honestly and skillfully done."Publisher's Weekly (Starred Review)

-

Carroll's quietly powerful story offers a courageous, cleareyed vision of a broken family while exploring the meaning of forgiveness. An honest and probing memoir of coming to terms with family.Kirkus

-

"Beautiful and rich....It's an emotional, high stakes ride as Leah discovers her mother's love for life, talent for photography, and the drug addiction that ultimately let to her murder. Leah's prose is beautiful, rich and dark. With each turn of the page you find yourself laughing...then feeling truly broken for Leah....Leaves the reader nostalgic and in awe."Providence Monthly

-

"Tough and dreamy, searching and sad, this debut memoir by a collateral victim of murder delves deep."Library Journal

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use