Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

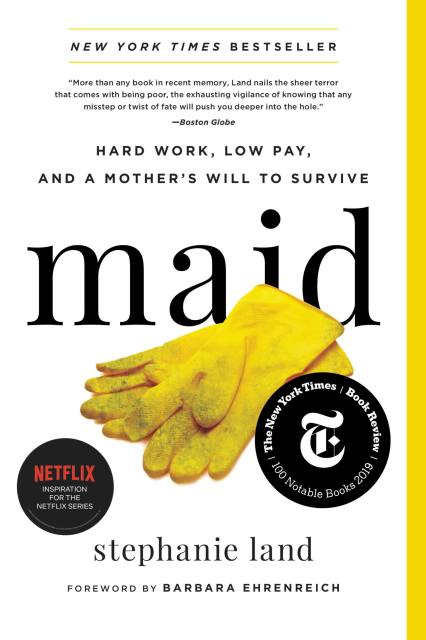

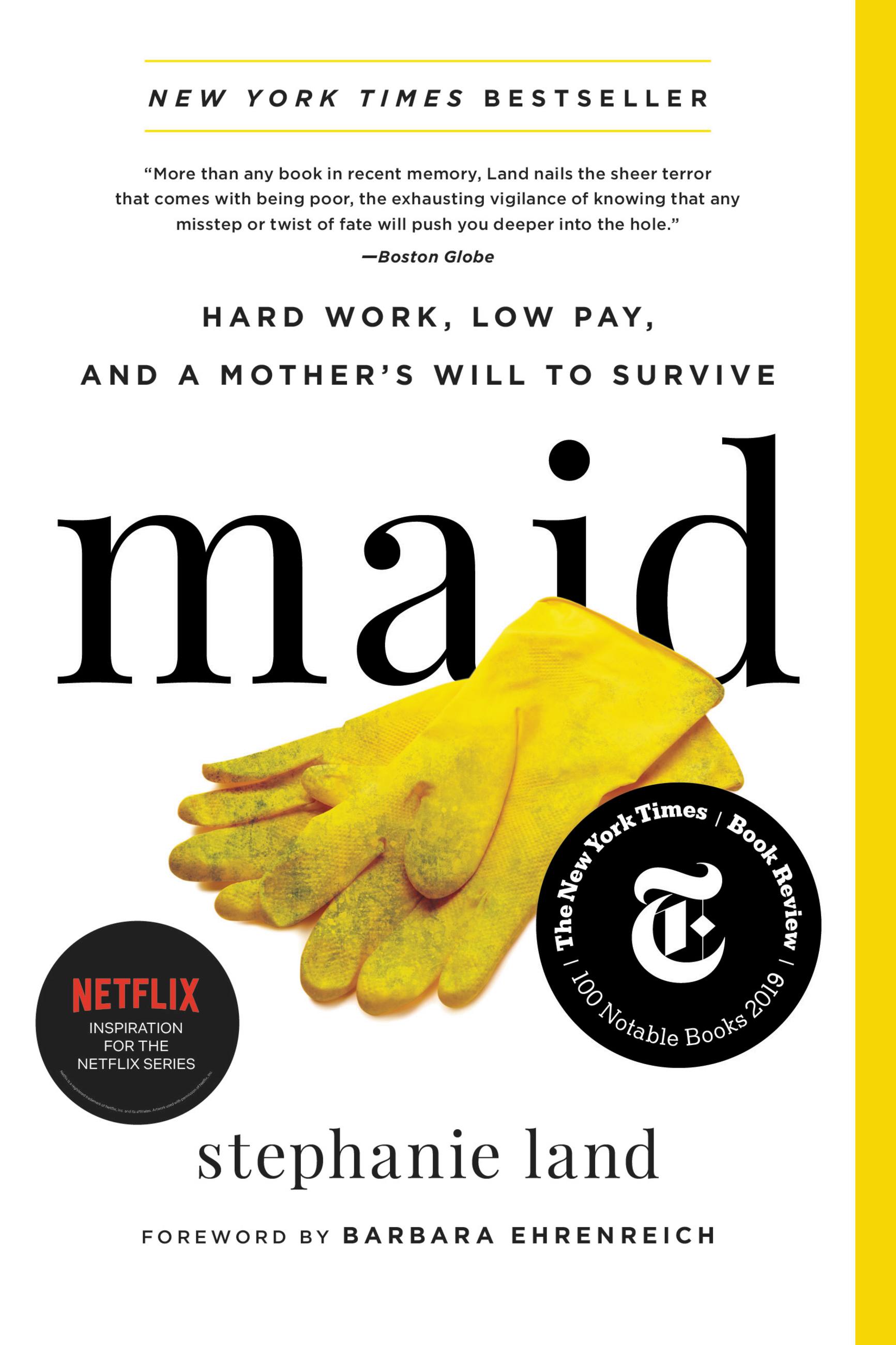

Maid

Hard Work, Low Pay, and a Mother's Will to Survive

Contributors

Foreword by Barbara Ehrenreich

Formats and Prices

Price

$18.99Price

$24.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $18.99 $24.99 CAD

- ebook $1.99 $1.99 CAD

- Hardcover $36.00 $46.00 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

- Audiobook CD (Unabridged) $30.00 $39.00 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around January 21, 2020. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

"A single mother's personal, unflinching look at America's class divide (Barack Obama)," this New York Times bestselling memoir is the inspiration for the Netflix limited series, hailed by Rolling Stone as "a great one."

At 28, Stephanie Land's dreams of attending a university and becoming a writer quickly dissolved when a summer fling turned into an unplanned pregnancy. Before long, she found herself a single mother, scraping by as a housekeeper to make ends meet.

Maid is an emotionally raw, masterful account of Stephanie's years spent in service to upper middle class America as a "nameless ghost" who quietly shared in her clients' triumphs, tragedies, and deepest secrets. Driven to carve out a better life for her family, she cleaned by day and took online classes by night, writing relentlessly as she worked toward earning a college degree. She wrote of the true stories that weren't being told: of living on food stamps and WIC coupons, of government programs that barely provided housing, of aloof government employees who shamed her for receiving what little assistance she did. Above all else, she wrote about pursuing the myth of the American Dream from the poverty line, all the while slashing through deep-rooted stigmas of the working poor.

Maid is Stephanie's story, but it's not hers alone. It is an inspiring testament to the courage, determination, and ultimate strength of the human spirit.

"A single mother's personal, unflinching look at America's class divide, a description of the tightrope many families walk just to get by, and a reminder of the dignity of all work." -PRESIDENT BARACK OBAMA, Obama's Summer Reading List

Maid is an emotionally raw, masterful account of Stephanie's years spent in service to upper middle class America as a "nameless ghost" who quietly shared in her clients' triumphs, tragedies, and deepest secrets. Driven to carve out a better life for her family, she cleaned by day and took online classes by night, writing relentlessly as she worked toward earning a college degree. She wrote of the true stories that weren't being told: of living on food stamps and WIC coupons, of government programs that barely provided housing, of aloof government employees who shamed her for receiving what little assistance she did. Above all else, she wrote about pursuing the myth of the American Dream from the poverty line, all the while slashing through deep-rooted stigmas of the working poor.

Maid is Stephanie's story, but it's not hers alone. It is an inspiring testament to the courage, determination, and ultimate strength of the human spirit.

"A single mother's personal, unflinching look at America's class divide, a description of the tightrope many families walk just to get by, and a reminder of the dignity of all work." -PRESIDENT BARACK OBAMA, Obama's Summer Reading List

Genre:

-

"A single mother's personal, unflinching look at America's class divide, a description of the tightrope many families walk just to get by, and a reminder of the dignity of all work."President Barack Obama, "Obama's 2019 Summer Reading List"

-

President Barack Obama, Summer Reading List (2019)Forbes, Most Anticipated Books of the YearGlamour, Best Books of the Year

Time, 11 New Books to Read This JanuaryVulture, 8 New Books You Should Read This JanuaryThrillist, All the Books We Can't Wait to Read in 2019USA Today, 5 New Books Not to Miss

Amazon, Best Books of the MonthDetroit News, New Books to Look Forward to in 2019The Missoulian, Best Books of the MonthSan Diego Entertainer, Books to Kick Off Your New YearPeople, Perfect for Your Book Club

Boston.com, 20 Books to Look Out for in 2019Hello Giggles, Best New Books to Read This WeekNewsweek, Best Books of 2019 So FarCNN Travel, Books You Should Read This SummerMental Floss, Summer Reading ListBookTrib, Books That Will Make You Look Smart at the Beach! -

"More than any book in recent memory, Land nails the sheer terror that comes with being poor, the exhausting vigilance of knowing that any misstep or twist of fate will push you deeper into the hole."The Boston Globe

-

"Stephanie Lands memoir [Maid] is a bracing one."The Atlantic

-

"An eye-opening journey into the lives of the working poor."People, Perfect for Your Book Club

-

"The particulars of Land's struggle are sobering, but it's the impression of precariousness that is most memorable."The New Yorker

-

"[Land's] book has the needed quality of reversing the direction of the gaze. Some people who employ domestic labor will read her account. Will they see themselves in her descriptions of her clients? Will they offer their employees the meager respect Land fantasizes about? Land survived the hardship of her years as a maid, her body exhausted and her brain filled with bleak arithmetic, to offer her testimony. It's worth listening to."New York Times Book Review

-

"What this book does well is illuminate the struggles of poverty and single-motherhood, the unrelenting frustration of having no safety net, the ways in which our society is systemically designed to keep impoverished people mired in poverty, the indignity of poverty by way of unmovable bureaucracy, and people's lousy attitudes toward poor people... Land's prose is vivid and engaging... [A] tightly-focused, well-written memoir... an incredibly worthwhile read."Roxane Gay, New York Times bestselling author of Bad Feminist and Hunger: A Memoir

-

"An eye-opening exploration of poverty in America."Bustle

-

"Marry the evocative first person narrative of Educated with the kind of social criticism seen in Nickel and Dimed and you'll get a sense of the remarkable book you hold in your hands. In Maid, Stephanie Land, a gifted storyteller with an eye for details you'll never forget, exposes what it's like to exist in America as a single mother, working herself sick cleaning our dirty toilets, one missed paycheck away from destitution. It's a perspective we seldom see represented firsthand-and one we so desperately need right now. Timely, urgent, and unforgettable, this is memoir at its very best."Susannah Cahalan, #1 New York Times bestselling author of Brain on Fire: My Month of Madness

-

"For readers who believe individuals living below the poverty line are lazy and/or intellectually challenged, this memoir is a stark, necessary corrective.... [T]he narrative also offers a powerful argument for increasing government benefits for the working poor during an era when most benefits are being slashed.... An important memoir that should be required reading for anyone who has never struggled with poverty."Kirkus Reviews, starred review

-

"Maid provides an important look at the morass of difficulties faced by the working poor."Elle Magazine

-

"[A] heartfelt and powerful debut memoir.... Land's love for her daughter... shines brightly through the pages of this beautiful, uplifting story of resilience and survival."Publishers Weekly, starred review

-

"[A] vivid and visceral yet nearly unrelenting memoir... Her journey offers an illuminating read that should inspire outrage, hope, and change."Library Journal

-

"Raw...Land [is] a gifted storyteller...Offers moments of levity...[Maid] shows we need to create an economy in which single motherhood and the risk of poverty do not go hand in hand."Ms. Magazine

-

"A heartfelt memoir."Harvard Business Review

-

"Maid delves into her time working for the upper middle class in the service industry, and in it, uncovers the true strength of the human spirit."San Diego Entertainer, Books to Kick Off Your New Year

-

"In writing about the spaces outside of her work, though, Land gives shape to the depleting anxiety and isolation that accompany motherhood in poverty for millions of Americans."The Nation

-

"[An] example of the determination and grace [is] on display in her memoir, in which she renders vividly the back-breaking and often surreal work of deep-cleaning strangers' homes while navigating the baffling bureaucracies of government assistance programs."Salon

-

"The book, with its unfussy prose and clear voice, holds you. It's one woman's story of inching out of the dirt and how the middle class turns a blind eye to the poverty lurking just a few rungs below -- and it's one worth reading."The Washington Post

-

"It is with beautiful prose that Land chronicles her time working as a housekeeper to make ends meet...Captur[es] the experience of hardworking Americans who make little money and are often invisible to their employers."Boston.com, 20 Books to Read in 2019

-

"Fascinating...Communicates clearly the challenges of a marginal existence as a single mother living in poverty as she sought to provide a stable and predictable home for her daughter in a situation that was anything but stable and predictable."The Columbus Dispatch

-

"Takes readers inside the gritty, unglamorous life of the underpaid, overworked people who serve the upper-middle class for a living."Parade

-

"Stephanie Land strips class divisions bare in her phenomenal memoir Maid, providing a profoundly important expose on the economy of being a single mother in America. This is the warrior cry from the tired, the poor, the huddled masses, reminding us to change our lives and remember how to see each other. Standing ovation. Not since Barbara Ehrenreich's Nickel and Dimed has the working woman's real life been so honestly illuminated."Lidia Yuknavitch, author of The Book of Joan

-

"In a country whose frayed safety net gets less policy attention than the marginal tax rate, Land is the anomaly not only in surviving to tell the tale - and in telling it with such compelling economy."Vulture, 8 New Books You Should Read this January

-

"Land's memoir forces readers to examine their implicit judgments about what we mean by the value of hard work in America and societal expectations of motherhood."Electric Lit

-

"Honest, unapologetic, and beautifully written."Hello Giggles

-

"Tells an honest story many are too afraid to examine."SheKnows.com

-

"A moving, intimate, essential account of life in poverty."Entertainment Weekly, Must List

-

"The next time you hear someone say they think poor people are lazy, hand them a copy of Maid."Minneapolis Star-Tribune

-

"Stephanie Land's heartrending book, Maid, provides a trenchant reminder that something is amiss with the American Dream and gives voice to the millions of 'working poor' toiling in a country that needs them but doesn't want to see them. A sad and hopeful tale of being on the outside looking in, the author makes us wonder how'd we fare scrubbing and vacuuming away the detritus of an affluence that always seems beyond reach."Steve Dublanica, New York Times bestselling author of Waiter Rant

-

"In a perfect world, Maid would become required reading in schools across the country."North Bay Bohemian

-

"As a solo mom and former house cleaner, this brave book resonated with me on a very deep level. We live in a world where the solo mother is an incomplete story: adrift in the world without a partner, without support, without a grounding, centering (male) force. But women have been doing this since the dawn of time, and Stephanie Land is one of millions of solo moms forced to get blood from stone. She is at once an old and new kind of American hero. This memoir of resilience and love has never been more necessary."Domenica Ruta, New York Times bestselling author of With or Without You

-

"A fun read."South Platte Sentinel

-

"Maid is a testament to a young mother's survival skills - a constantly shifting balance of back-breaking labor, single-parenting responsibilities, complying with rules and regulations, college course-work, attitude adjustments and diplomacy on all fronts... The book is a gift of hope and joy for anyone lucky enough to see beyond blame."Wicked Local

-

"It's as much a story about resilience as it is a hard look at current systems in place to help impoverished people and how hard they are to navigate. It's eye-opening and inspiring--a definite must-read!"Style Blueprint

-

"If this memoir doesn't shake you up and give you a stronger understanding of poverty in America, your heart must be made of coal. Stephanie Land, who spent years in poverty, clues you in to what it's really like to live in a shelter. It's hard to think that a white paper or TV documentary could say it as well as she does."Florida Times-Union

-

"Maid is an important work of journalism that offers an insightful and unique perspective on a segment of the working poor from someone who has lived it."Amazon Book Review

-

"I loved this story about one woman surviving impossible circumstances."Reese Witherspoon

-

"An empowering story of a woman determined to pull herself up in life through which we all feel stronger!"Gretchen Carlson, Politico

-

"Maid is a beautiful book and a sad book and even, at times, a joyful book--a story of a mother's love for her daughter--but most of all it's an important book about the U.S. economy and what it does to people."Daily Kos

-

"Maid-part Educated, part Hillbilly Elegy-is an eye-opening portrait of how privilege and the female working class can commingle."Glamour

- On Sale

- Jan 21, 2020

- Page Count

- 288 pages

- Publisher

- Legacy Lit

- ISBN-13

- 9780316505093

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use