Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

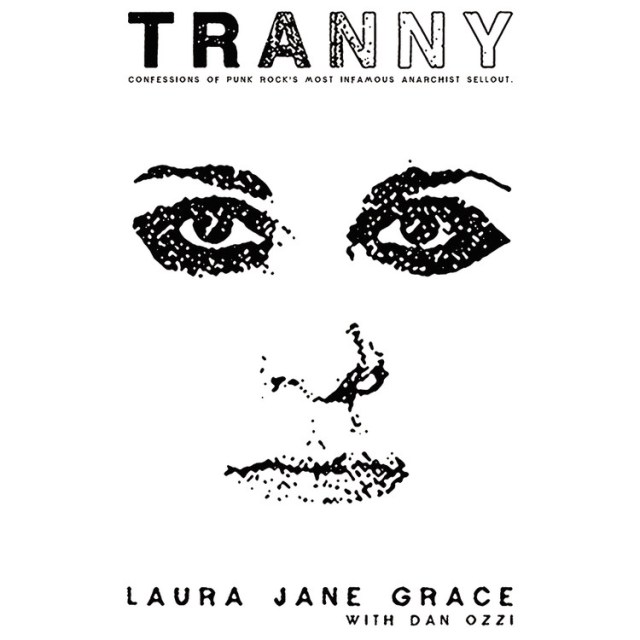

Tranny

Confessions of Punk Rock's Most Infamous Anarchist Sellout

Contributors

With Dan Ozzi

Read by Laura Jane Grace

Formats and Prices

Format

Format:

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

- ebook $13.99 $17.99 CAD

- Trade Paperback $19.99 $25.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around November 15, 2016. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

It began in a bedroom in Naples, Florida, when a misbehaving punk teenager named Tom Gabel, armed with nothing but an acoustic guitar and a headful of anarchist politics, landed on a riff. Gabel formed Against Me! and rocketed the band from its scrappy beginnings-banging on a drum kit made of pickle buckets-to a major-label powerhouse that critics have called this generation’s The Clash. Since its inception in 1997, Against Me! has been one of punk’s most influential modern bands, but also one of its most divisive. With every notch the four-piece climbed in their career, they gained new fans while infuriating their old ones. They suffered legal woes, a revolving door of drummers, and a horde of angry, militant punks who called them “sellouts” and tried to sabotage their shows at every turn.

But underneath the public turmoil, something much greater occupied Gabel-a secret kept for 30 years, only acknowledged in the scrawled-out pages of personal journals and hidden in lyrics. Through a troubled childhood, delinquency, and struggles with drugs, Gabel was on a punishing search for identity. Not until May of 2012 did a Rolling Stone profile finally reveal it: Gabel is a transsexual, and would from then on be living as a woman under the name Laura Jane Grace.

Tranny is the intimate story of Against Me!’s enigmatic founder, weaving the narrative of the band’s history, as well as Grace’s, with dozens of never-before-seen entries from the piles of journals Grace kept. More than a typical music memoir about sex, drugs, and rock ‘n’ roll-although it certainly has plenty of that-Tranny is an inside look at one of the most remarkable stories in the history of rock.

Genre:

-

Normal0falsefalsefalseEN-USX-NONEX-NONEMicrosoftInternetExplorer4 "Laura Jane Grace shows great bravery diving into every detail of a story seldom told, with the advantage of having kept journals documenting everything she went through, from childhood to the beginnings of her band. Capturing the pain and struggle, self-doubt and lack of support she experienced, Grace provides a valuable starting point for a conversation to broaden the understanding of, and empathy for, trans people."Joan Jett, Billboard's 100 Greatest Music Books of All Time

-

"An ambassador for the gender revolution currently sweeping through public restroom policy and National Geographic covers [and] a potent tool for empathy that hasn't quite existed in pop culture....Grace and co-writer Dan Ozzi spin green room drama and rock star recklessness into a gem of a rock bio that belongs on a shelf alongside Hammer of the Gods and Get in the Van."Paste Magazine, Best Nonfiction Books of 2016

-

"A full-length tell-all about Grace's lifelong journey to discovering, accepting, and at last publicly acknowledging her true identity....[told] with daring candor...the memoir establishes her as at once a transgender icon and a modern day heroine."Harper's Bazaar, Best Books of November

-

"A savagely candid transgender memoir, and thus far, the only quintessential text regarding Against Me!--one of the most significant punk bands of the aughts and onward. Without a smidgen of sarcasm, I would highly recommend the book to your grandmother, even if she is afraid of transpeople and can't name three Clash songs."Esquire

-

"In this riveting and at times harrowing biography, Grace recounts in unflinching detail her path to self-realization....The story [of the band] would be enough for a compelling book, but Grace's gender dysphoria adds a remarkable twist to the tale....[a] brutally honest, soul-searching memoir."Publishers Weekly (starred review)

-

"An engrossing story about the perils of the rock star lifestyle, identity, drug abuse, and what it means to be a punk."Third Coast Review, Best Music and Art of 2016

-

"The extraordinary story of the misfit among the punks who attempted to save himself by choosing his gender--as if by erasing the man he was might heal the diseased society that produced him. Laura Jane Grace claws her way into the light and we are all inspired to find our own grace."John Cameron Mitchell

-

"Laura Jane Grace has pulled off the near impossible. With her first book, Tranny, she has added a new perspective to a vastly over populated genre of music-based literature.Shirley Manson, lead singer of Garbage

In doing so, she has also managed to tell her own deeply personal, at times heartbreaking, story of her struggle with gender identity in a society still content to ascribe gender using an archaic binary system that drives so many transgender people to despair.

This book is a mandatory read for anyone interested in gender identity, intellectual punk rock, or an engrossing account of a great rock and roll band, subjects that may sound mutually exclusive but here are inextricably linked." -

"Grace writes about juggling the pressures of grappling with dysphoria and keeping her band together with such naked honesty that you can feel the weight being lifted off of her shoulders....A page turner that brims with hard emotional truth....A poignant and timely look at a still-emerging cultural issue worthy of serious discussion."A.V. Club

-

"Potent...Grace writes viscerally about her experiences grappling with this condition throughout her life."Rolling Stone

-

"A powerful, disarmingly honest portrait of becoming."Entertainment Weekly

-

"What does it mean to be an authentic musician? The question doesn't sound like good fodder for a book - it's too woolly, too late-night-dorm-room. And yet, in part because it asks the question over and over, Against Me! front woman Laura Jane Grace's memoir works wonderfully."Vulture

-

"The real power of Tranny comes from Grace's journal entries, which tell the real-time story of a quest for self that winds through addiction, divorce, and, ultimately, action to address the agonizing dysphoria."The New York Times Book Review

-

"Tranny is an intimate, sometimes appropriately messy account of Grace's career as a musician and agitator, full of on-the-road indulgences and off-the-clock struggles. It's as honest as any Against Me! tune, and just as hooky."Wired

-

"A poignant, brave, and at times funny story about struggling to fit into a community but feeling biologically out of place....Both fascinating and entertaining. It's also sometimes heartbreaking."Yahoo! Music

- On Sale

- Nov 15, 2016

- Publisher

- Hachette Audio

- ISBN-13

- 9781478940180

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use