Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

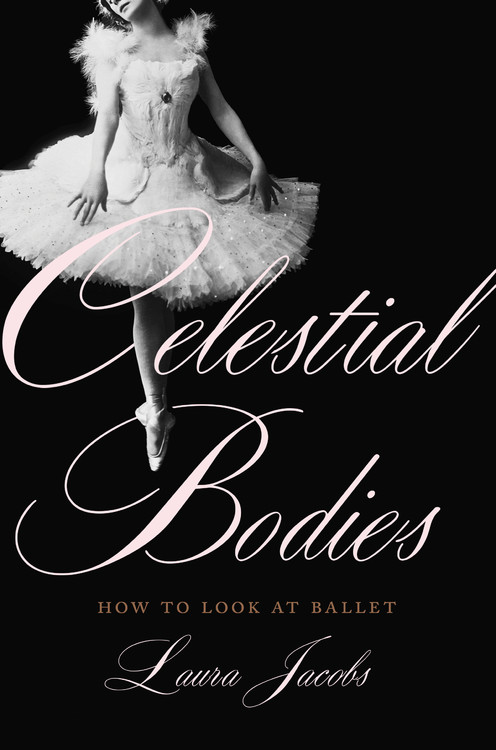

Celestial Bodies

How to Look at Ballet

Contributors

By Laura Jacobs

Formats and Prices

Price

$27.00Price

$35.50 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $27.00 $35.50 CAD

- ebook $16.99 $21.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around May 8, 2018. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

As much as we may enjoy Swan Lake or The Nutcracker, for many of us ballet is a foreign language. It communicates through movement, not words, and its history lies almost entirely abroad — in Russia, Italy, and France. In Celestial Bodies, dance critic Laura Jacobs makes the foreign familiar, providing a lively, poetic, and uniquely accessible introduction to the world of classical dance. Combining history, interviews with dancers, technical definitions, descriptions of performances, and personal stories, Jacobs offers an intimate and passionate guide to watching ballet and understanding the central elements of choreography.

Beautifully written and elegantly illustrated with original drawings, Celestial Bodies is essential reading for all lovers of this magnificent art form.

Genre:

-

"Jacobs's book opens the door, offering a meticulous introduction to the art form and welcoming readers to have a seat and stay a while.... It's from this insider's perspective that Jacobs is able to offer an all-encompassing guided tour behind the curtain, then circling back to the auditorium where the balletomane, the occasional fan and the newcomer sit side by side as they interpret the performance according to their individual experiences and beliefs."Misty Copeland, New York Times Book Review

-

"A lively guide, for the newcomer and enthusiast alike, to an art form that is meticulously controlled yet ever-changing."Wall Street Journal

-

"Our dance critic Laura Jacobs is the best writer on ballet there is. So you can bet that her new book, Celestial Bodies: How to Look at Ballet, will be the best primer on ballet there is."New Criterion

-

"In 12 chapters Jacobs provides readers a whirlwind tour of ballet, effortlessly weaving together history, technique, music, choreography, drama."Ballet Focus

-

"Whether you are budding balletomane or a lifelong dancer, Celestial Bodies will inspire you to look more closely at our beloved art form-and fall more deeply in love with it."Pointe Magazine

-

"This sparkling, eloquent book will make going to the ballet a richer experience for both the novice and the passionate."Haglund's Heel

-

"Lyrical and accessible...Jacobs brings over two decades' worth of her experience as a dance critic to this elegant introduction to all aspects of the art form: its cultural history, the development of its aesthetics, its famous works and epic personalities."Times Literary Supplement

-

"Written like a true dancer...It's from this insider's perspective that Jacobs is able to offer an all-encompassing guided tour behind the curtain, then circling back to the auditorium where the balletomane, the occasional fan and the newcomer sit side by side as they interpret the performance according to their individual experiences and beliefs."New York Times Book Review

-

"According to the artist and critic Alexandre Benois, 'Ballet is perhaps the most eloquent of all spectacles.' This book is one of the most eloquent ever written about it."Booklist

-

"The author ably explains the technical aspects of ballet, as when she explains that turnout's 'symmetrical torque in the hips engages energy and concentrates it' and in her beautiful description of pas de deux: 'a form of close-up, the theatrical equivalent of the camera's lavish gaze.' 'They're doing choreography,' Danny Kaye sang in White Christmas. As Jacobs demonstrates, however, ballet is so much more."KirkusReviews

-

"Laura Jacobs' Celestial Bodies is original, rich in discovery, and conceived in prose that is as agile and graceful as her subject matter."Sascha Radetsky, American Ballet Theatre

-

"What makes ballet magical? With a brief recap of its origins and a poetic analysis of its positions, Laura Jacobs gives us the benefit of her perceptions over the course of a distinguished career in the audience. For those coming to ballet for the first time-and those of us who have been watching ballet for years-she offers a lesson in appreciation. The best way to watch, she tells us, is "with an open heart." This graceful book is the product of her own heart and her sprightly mind."Holly Brubach, award-winning dance historian and cultural critic

-

"Laura Jacobs' book about the art of ballet, which takes the form of a higher kind of how-to book, is itself a work of art. I would call it perfect, but Jacobs spells out the limits of the ideal of perfection. Better to call it alive, expressive, moving, wise."Paul Elie, author of ReinventingBach

- On Sale

- May 8, 2018

- Page Count

- 272 pages

- Publisher

- Basic Books

- ISBN-13

- 9780465098477

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use