Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

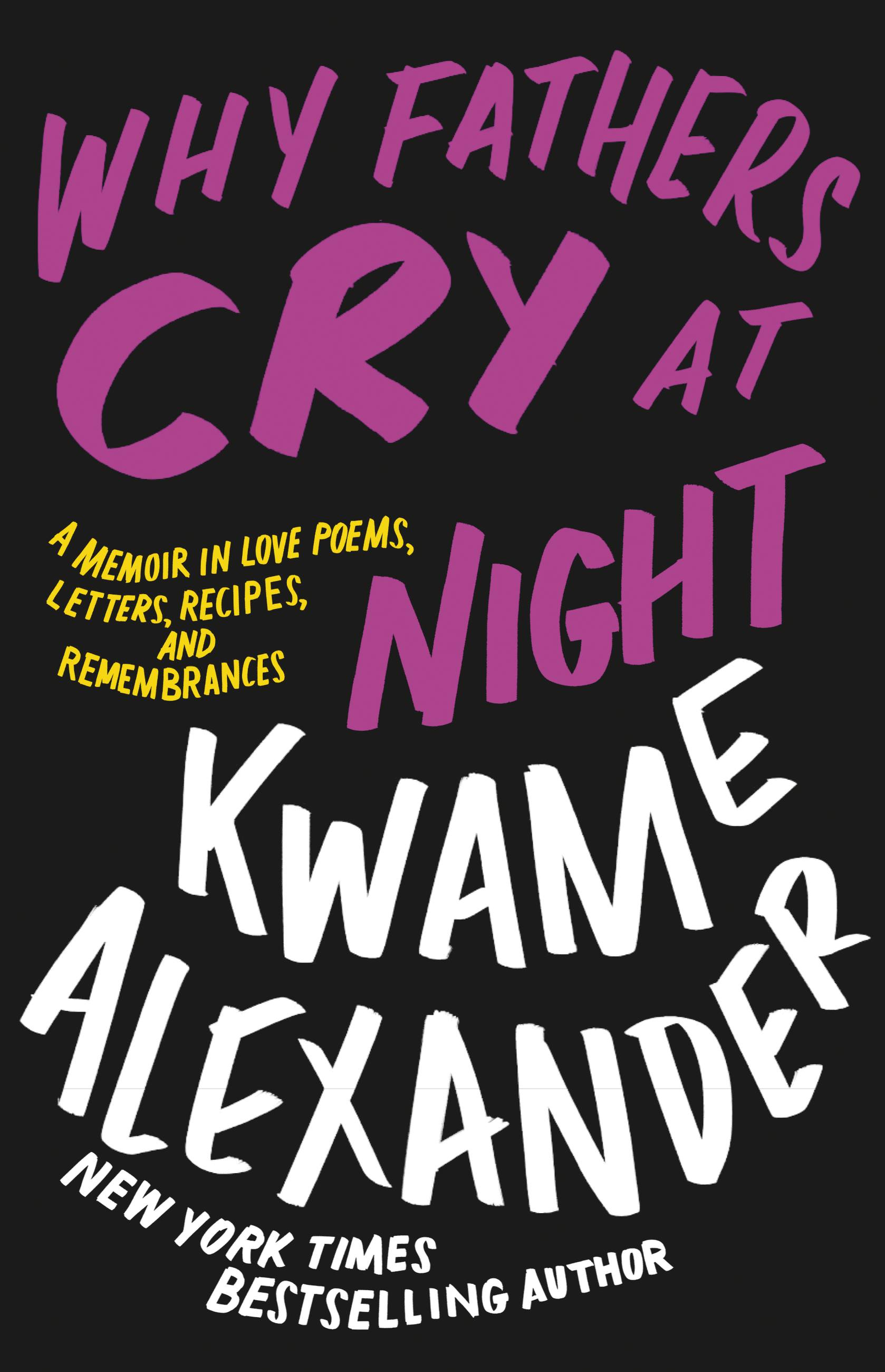

Why Fathers Cry at Night

A Memoir in Love Poems, Letters, Recipes, and Remembrances

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$28.00Price

$35.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $28.00 $35.00 CAD

- ebook $14.99 $19.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $18.99

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around May 23, 2023. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

This powerful memoir from a #1 New York Times bestselling author and Newbery Medalist features poetry, letters, recipes, and other personal artifacts that provide an intimate look into his life and the loved ones he shares it with.

In an intimate and non-traditional (or "new-fashioned") memoir, Kwame Alexander shares snapshots of a man learning how to love. He takes us through stories of his parents: from being awkward newlyweds in the sticky Chicago summer of 1967, to the sometimes-confusing ways they showed their love to each other, and for him. He explores his own relationships—his difficulties as a newly wedded, 22-year-old father, and the precariousness of his early marriage working in a jazz club with his second wife. Alexander attempts to deal with the unravelling of his marriage and the grief of his mother's recent passing while sharing the solace he found in learning how to perfect her famous fried chicken dish. With an open heart, Alexander weaves together memories of his past to try and understand his greatest love: his daughters.Full of heartfelt reminisces, family recipes, love poems, and personal letters, Why Fathers Cry at Night inspires bravery and vulnerability in every reader who has experienced the reckless passion, heartbreak, failure, and joy that define the whirlwind woes and wonders of love.

Genre:

-

"Written with candor, warmth, and heart-wrenching grace, Why Fathers Cry at Night is nothing short of a marvel, animating humanity’s most important questions: What does it mean to grieve, to have the courage to surrender, to find a home in this tumultuous world, and to learn to love again? With radiance and poetic precision, Kwame Alexander’s words will remind you of art’s infinite sustenance. As soon as I turned the last page, I started again."Adrienne Brodeur, author of the best-selling memoir Wild Game: My Mother, Her Lover and Me (2019)

- On Sale

- May 23, 2023

- Page Count

- 240 pages

- Publisher

- Little, Brown and Company

- ISBN-13

- 9780316417228

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use