Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

Has China Won?

The Chinese Challenge to American Primacy

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$30.00Price

$38.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $30.00 $38.00 CAD

- ebook $17.99 $21.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

- Trade Paperback $17.99

- Trade Paperback $19.99 $25.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around March 31, 2020. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

China and America are world powers without serious rivals. They eye each other warily across the Pacific; they communicate poorly; there seems little natural empathy. A massive geopolitical contest has begun.

America prizes freedom; China values freedom from chaos.

America values strategic decisiveness; China values patience.

America is becoming society of lasting inequality; China a meritocracy.

America has abandoned multilateralism; China welcomes it.

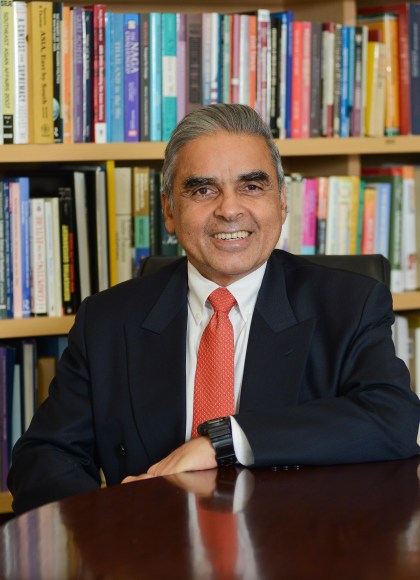

Kishore Mahbubani, a diplomat and scholar with unrivalled access to policymakers in Beijing and Washington, has written the definitive guide to the deep fault lines in the relationship, a clear-eyed assessment of the risk of any confrontation, and a bracingly honest appraisal of the strengths and weaknesses, and superpower eccentricities, of the US and China.

Genre:

-

Praise for Has China Won?David M. Lampton : Oksenberg-Rohlen Fellow at the Freeman Spogli Institute, Asia-Pacific Research Center, Stanford University; Professor Emeritus, Johns Hopkins-SAIS.

"Americans should heed Kishore Mahbubani's astringent advice, unwelcome as it may be: Cast away illusions about eternal U.S. primacy and exceptional virtue protected by high walls. Instead, Washington should adopt a long-term international strategy anchored in balance and cooperation; reestablish sound internal leadership and governance; win friends abroad instead of driving allies away; avoid over-commitment; and express moral modesty. Military power is not the most important weapon in the Arsenal of Democracy." -

"China and the US are locked in a struggle for international primacy, and the result of this contest will shape the world order for generations to come. Kishore captures the complexity of this battle with the measured nuance and clear insight it deserves. Not to be missed."Ian Bremmer, author of Us vs. Them and president, Eurasia Group

-

"Kishore Mahbubani's Has China Won? is a serious contribution: reviewing strategic wisdom from Kennan to Kennedy, asking provocative, even heretical questions about China's rise, and counseling a world safe for diversity."Graham Allison, author of Destined For War: Can America and China escape Thucydides's Trap, is the Douglas Dillon Professor of Government, Harvard University

-

"Kishore Mahbubani has deep experience in diplomacy and international relations, an highly-developed relatively rare ability to think strategically in complex settings, and a unique capacity (by virtue of his life story) to connect with and respect multiple civilizations and their values. These skills, insights and experience are on full display in his new book, "Has China Won?" A provocative title, but a little misleading. In fact, he analyzes in an even-handed way the scenarios that could play out in the emerging rivalry between China and the USA. His assessment of the biases and mistakes on both sides is both brutal and crucial. It will take most readers out of their comfort zone, and that is part of its strength. There are many insights, but at the core, is the proposition that the outcome over time will depend mainly on the capacity (or its absence) on both sides, to understand and respect deep differences in civilizations that are built over hundreds and even thousands of years, ones that lead to varying governance structures and relative values with respect to individual freedoms, social and political stability and more; in other words seeing the worlds through the eyes of the other. That said there is a wide range of common interests on which to build. Notwithstanding the title of the book, it is fairly clear by the end that in Mahbubani's view, either everyone (not just China and the USA) wins or no one wins. It is an important book at a crucial moment in history."Michael Spence was conferred the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences in 2001

-

"Has China Won? is a provocative title. In his latest book, Kishore Mahbubani explains why this is in fact the wrong question to ask. Despite rising resentment and mutual misperception, both the United States and China ultimately know that war between them will be cataclysmic. In this revelatory new book, Mahbubani appeals to the deeper rationality of both great powers, arguing that the greatest challenge of our times will be to answer the question of whether humanity has won. Both American and Chinese readers will benefit from Mahbubani's wisdom."George Yeo, former Minister of Foreign Affairs, Singapore

-

"Kishore Mahbubani has long extolled what the West taught the rest of the world and how many parts of Asia, including China and India, have benefitted from what they have learnt. Yet no one seems more surprised at what China has learned from the US than the United States itself, which now sees China purely as a rival that threatens its global primacy. Mahbubani asks pointedly: what did China do to deserve this? He has gone further than ever before to challenge his readers to think of the consequences if the rivalry is allowed to grow unchecked."Wang Gungwu, University Professor at the National University of Singapore

-

"Kishore Mahbubani has a remarkable ability to see through the complacent orthodoxies that lead great nations astray. Has China Won? identifies the myths and mistakes that are undermining Chinese and American relations with each other and the world, and it offers both countries candid and clear-eyed advice for how to do better in the future. Leaders in Beijing and Washington will not like everything he has to say, but they would do well to pay close attention to it anyway. And so should you."Stephen M. Walt is the Robert and Renée Belfer Professor of International Affairs at Harvard University

-

"We need to know how China thinks and sees itself in the world, whether we see them as our friends, our adversary, or somewhere in between. There is no better guide for westerners to the Asian world view than Kishore Mahbubani. He shares the wealth of his knowledge and experience in this vitally important book."Lawrence H. Summers is a former President of Harvard University and a former Treasury Secretary

-

"Kishore Mahbubani has written an excellent and important book on much the biggest question in international affairs: how will the relationship between the US and China evolve? Humanity desperately needs these superpowers to co-operate. It seems more likely to have ceaseless friction between them. If it is the latter, argues Mahbubani, it is quite likely that the US will end up at a severe disadvantage, not so much because of China's inherent superiority, but rather because of US mistakes, not least a failure to grasp the Chinese reality."Martin Wolf, Chief Economics Commentator at the Financial Times

-

"With his usual lucidity and provocativeness, Kishore Mahbubani has written yet another cool-headed analysis of a subject of great importance for the world's future."The International Institute of Strategic Studies

- On Sale

- Mar 31, 2020

- Page Count

- 320 pages

- Publisher

- PublicAffairs

- ISBN-13

- 9781541768130

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use