Promotion

Shop now and save 20% on your back-to-school purchases & get free shipping on orders $45+ Use code: SCHOOL24

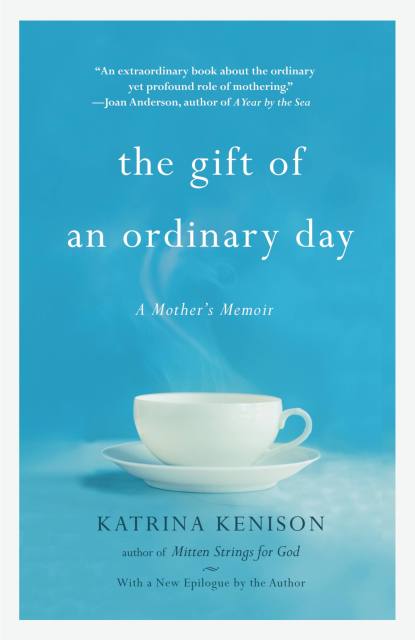

The Gift of an Ordinary Day

A Mother's Memoir

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$11.99Price

$15.99 CADFormat

Format:

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around September 7, 2009. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

The Gift of an Ordinary Day is an intimate memoir of a family in transition, with boys becoming teenagers, careers ending and new ones opening up, and an attempt to find a deeper sense of place—and a slower pace—in a small New England town.

This is a story of mid-life longings and discoveries, of lessons learned in the search for home and a new sense of purpose, and the bittersweet intensity of life with teenagers—holding on, letting go.

Poised on the threshold between family life as she's always known it and her older son's departure for college, Kenison is surprised to find that the times she treasures most are the ordinary, unremarkable moments of everyday life, the very moments that she once took for granted, or rushed right through without noticing at all.

The relationships, hopes, and dreams that Kenison illuminates will touch women's hearts, and her words will inspire mothers everywhere as they try to make peace with the inevitable changes in store.

This is a story of mid-life longings and discoveries, of lessons learned in the search for home and a new sense of purpose, and the bittersweet intensity of life with teenagers—holding on, letting go.

Poised on the threshold between family life as she's always known it and her older son's departure for college, Kenison is surprised to find that the times she treasures most are the ordinary, unremarkable moments of everyday life, the very moments that she once took for granted, or rushed right through without noticing at all.

The relationships, hopes, and dreams that Kenison illuminates will touch women's hearts, and her words will inspire mothers everywhere as they try to make peace with the inevitable changes in store.

-

This eloquent book is ...about longing and fulfillment , taking stock of failures and achievements, a search for the elusive "something more" of one's existence-and a reminder that life's seemingly mundane moments are often where we find beauty, grace and transformation.Family Circle Magazine

-

"Kenison writes so beautifully and clearly about what is most important in family life."Jane Hamilton, author of A Map of the World and Laura Rider's Masterpiece

-

An honest, graceful book that every parent will appreciate. In the thick of challenging changes, emotional troughs, and tender realizations the reader will find comfort and guidance. Here is a fine writer, a dedicated mother, and a spiritual seeker speaking intimately to parents in search of wisdom."Thomas Moore, author of Care of the Soul and Writing in the Sand

-

How I admire this mid-life mom, who writes with strong contemplative spirit and a heart wide open to change. Her memoir is a courageous and generous contribution to deepening American family life.Nancy Mellon, author of Body Eloquence

-

"The Gift of an Ordinary Day is much more than a memoir of motherhood; it is an inspired and inspiring meditation on midlife. What Katrina Kenison gives mothers-her gift-is the promise of reinventing ourselves as our kids grow up and we grow older, and the assurance of an invitingly abundant landscape on the far side of parenthood."Lisa Garrigues, author of Writing Motherhood

- On Sale

- Sep 7, 2009

- Page Count

- 320 pages

- Publisher

- Grand Central Publishing

- ISBN-13

- 9780446558099

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use