Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

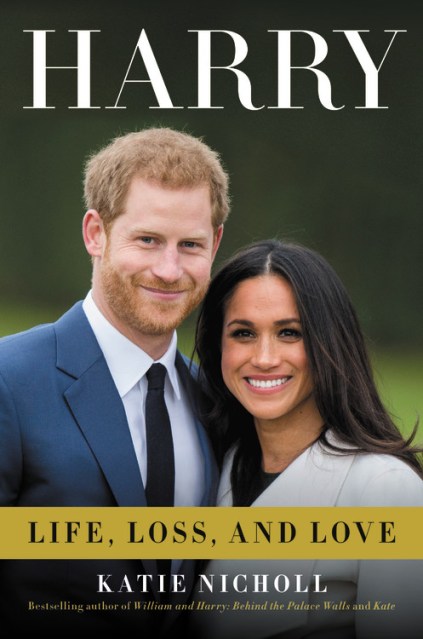

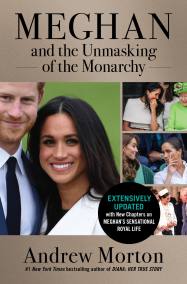

Harry

Life, Loss, and Love

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$27.00Price

$34.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $27.00 $34.99 CAD

- ebook $13.99 $17.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

- Trade Paperback (Revised) $16.99 $22.49 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around March 20, 2018. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

From his earliest public appearances as a mischievous redheaded toddler, Prince Harry has captured the hearts of royal enthusiasts around the world. In Harry, Britain’s leading expert on the young royals offers an in-depth look at the wayward prince turned national treasure. Nicholl sheds new light on growing up royal, Harry’s relationship with his mother, his troubled youth and early adulthood, and how his military service in Afghanistan inspired him to create his legacy, the Invictus Games.

Harry: Life, Loss, and Love features interviews with friends, those who have worked with the prince, and former Palace aides. Nicholl explores Harry’s relationship with his family, in particular, the Queen, his father, stepmother, and brother, and reveals his secret “second family” in Botswana. She uncovers new information about his former girlfriends and chronicles his romance and engagement to American actress Meghan Markle.

Harry is a compelling portrait of one of the most popular members of the royal family, and reveals the inside story of the most intriguing royal romance in a decade.

Genre:

-

"Nicholl's Harry: Life, Loss, and Love reveals... intimate glimpses into the already highly scrutinized lives of Meghan and Harry."Slate.com

-

"Romance lovers will be happy."USA Today

-

"Through interviews with friends, acquaintances, and confidants, best-selling author and Vanity Fair royals correspondent Katie Nicholl delivers a deep dive into the life of Kensington's most improved prince."Vanity Fair

-

"The new Prince Harry book is hot...a must-read material for royal fans.The Globe and Mail

-

"Katie has become the go-to source on all things royal."KTLA.com

-

"Katie Nicholl has defined herself as an authority on the young royals.... The book turns to numerous inside sources for swoon-worthy accounts of their love, while also offering an in-depth look at Harry's life overall."Entertainment Weekly

-

"It's guaranteed that this tome will be . . . [eye-opening,] as Nicholl is deeply embedded in the royal scene."The New York Observer

-

"Royal reporter Katie Nicholl's well-researched new book Harry: Life, Loss and Love, takes a deep dive into the popular prince's story . . .[and] sheds light on Harry's private life, away from the spotlight, with his mother, brother and family-and now his future bride."Maclean's (Canada)

-

"Perfect for those who are fans of the royal family.... A Hollywood biography of a young leading man... for whom something momentous is happening."San Francisco Book Review

-

"We didn't think we could be any more obsessed with Prince Harry then we already were, but author Katie Nicholl just proved us all wrong. The royal expert just released her new biography on the ginger prince, Harry: Life, Loss, and Love-and quite frankly, it's legendary."Cheatsheet.com

-

"Intriguing."Marketwatch.com

-

"[A] crown jewel of a book."Bella Magazine

-

Praise for Katie Nicholl's William and Harry:

-

"If you want to know what really happens behind those closed palace doors, then this is the book for you."Piers Morgan

-

"Using her unrivalled sources [Katie Nicholl] has written the most revealing book ever about Princes William and Harry... the most vivid and engaging study yet of our future King."Mail on Sunday

-

"An entertaining, richly-photographed book... Nicholl retraces the well-known story of the boys' triumphs and travails... Chattily and fondly, Nicholl chronicles the boys' lives, and gives Kate ample and generous treatment."The New York Times

-

"Nicholl delves into the secret lives of William and Harry... [and] uncovers what makes the two young Windsors tick."USA Today

-

"Katie Nicholl has written [an] entertaining biography ... Harry and Meghan dishes on the lives of these rich, pretty, and seemingly good people in the most gentle, cheerful way."Deseret News

- On Sale

- Mar 20, 2018

- Page Count

- 272 pages

- Publisher

- Hachette Books

- ISBN-13

- 9781602865266

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use