Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

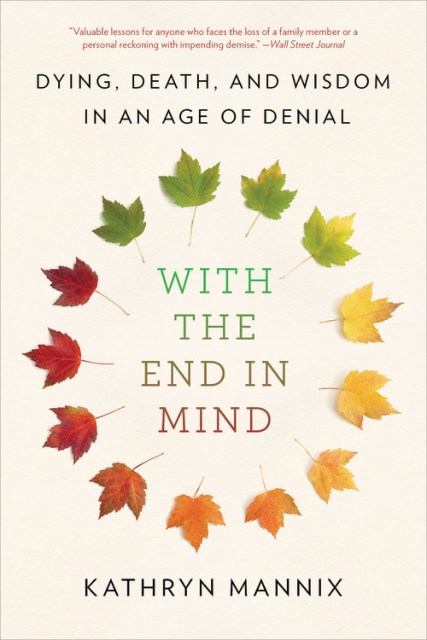

With the End in Mind

Dying, Death, and Wisdom in an Age of Denial

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$19.99Price

$25.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $19.99 $25.99 CAD

- ebook $2.99 $6.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around December 18, 2018. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

For readers of Atul Gawande and Paul Kalanithi, a palliative care doctor’s breathtaking stories from 30 years spent caring for the dying.

Modern medical technology is allowing us to live longer and fuller lives than ever before. And for the most part, that is good news. But with changes in the way we understand medicine come changes in the way we understand death. Once a familiar, peaceful, and gentle — if sorrowful — transition, death has come to be something from which we shield our eyes, as we prefer to fight desperately against it rather than accept its inevitability.

Dr. Kathryn Mannix has studied and practiced palliative care for thirty years. In With the End in Mind , she shares beautifully crafted stories from a lifetime of caring for the dying, and makes a compelling case for the therapeutic power of approaching death not with trepidation, but with openness, clarity, and understanding.

Weaving the details of her own experiences as a caregiver through stories of her patients, their families, and their distinctive lives, Dr. Mannix reacquaints us with the universal, but deeply personal, process of dying. With insightful meditations on life, death, and the space between them, With the End in Mind describes the possibility of meeting death gently, with forethought and preparation, and shows the unexpected beauty, dignity, and profound humanity of life coming to an end.

Modern medical technology is allowing us to live longer and fuller lives than ever before. And for the most part, that is good news. But with changes in the way we understand medicine come changes in the way we understand death. Once a familiar, peaceful, and gentle — if sorrowful — transition, death has come to be something from which we shield our eyes, as we prefer to fight desperately against it rather than accept its inevitability.

Dr. Kathryn Mannix has studied and practiced palliative care for thirty years. In With the End in Mind , she shares beautifully crafted stories from a lifetime of caring for the dying, and makes a compelling case for the therapeutic power of approaching death not with trepidation, but with openness, clarity, and understanding.

Weaving the details of her own experiences as a caregiver through stories of her patients, their families, and their distinctive lives, Dr. Mannix reacquaints us with the universal, but deeply personal, process of dying. With insightful meditations on life, death, and the space between them, With the End in Mind describes the possibility of meeting death gently, with forethought and preparation, and shows the unexpected beauty, dignity, and profound humanity of life coming to an end.

Genre:

-

"With sometimes unsettling detail, admirable empathy and a sprinkling of humor, Dr. Mannix imparts valuable lessons for anyone who faces the loss of a family member or a personal reckoning with impending demise."The Wall Street Journal

-

"With the End in Mind is one of the loveliest books I've ever read. It's part memoir and part self-help manual, part practical advice and part professional credo. Mannix's compassion is bottomless and her scrupulousness unimpeachable."Bookforum

- On Sale

- Dec 18, 2018

- Page Count

- 352 pages

- Publisher

- Little Brown Spark

- ISBN-13

- 9780316504478

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use