Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

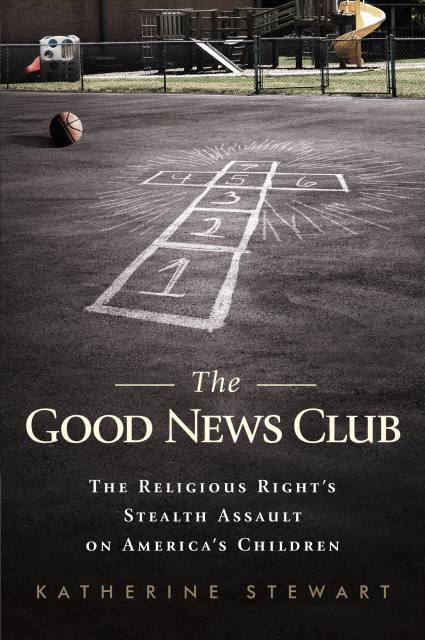

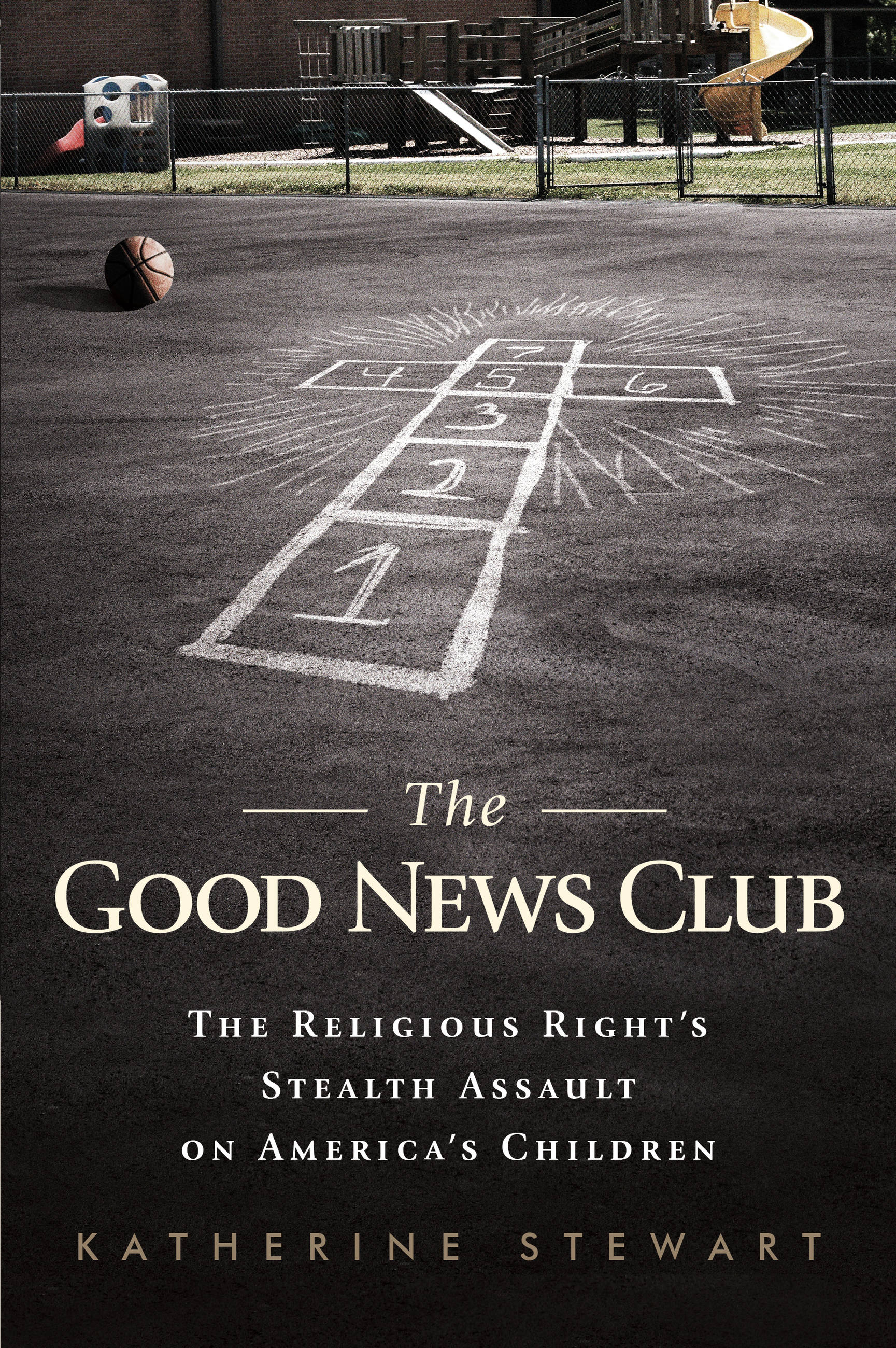

The Good News Club

The Christian Right's Stealth Assault on America's Children

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$9.99Price

$12.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $9.99 $12.99 CAD

- Hardcover $25.99 $29.00 CAD

- Trade Paperback $21.99 $28.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around January 24, 2012. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

Astonished to discover that the U.S. Supreme Court has deemed this — and other forms of religious activity in public schools — legal, Stewart set off on an investigative journey to dozens of cities and towns across the nation to document the impact. In this book she demonstrates that there is more religion in America’s public schools today than there has been for the past 100 years. The movement driving this agenda is stealthy. It is aggressive. It has our children in its sights. And its ultimate aim is to destroy the system of public education as we know it.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Jan 24, 2012

- Page Count

- 304 pages

- Publisher

- PublicAffairs

- ISBN-13

- 9781610390507

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use