Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

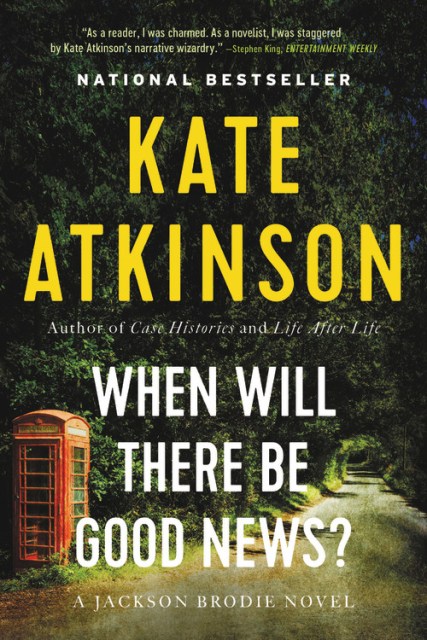

When Will There Be Good News?

A Novel

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$18.99Format

Format:

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around January 11, 2010. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

The third installment in Kate Atkinson’s wildly beloved series of Jackson Brodie Mysteries: a complex tale of murder, coincidence, and connected lives.

On a hot summer day, Joanna Mason’s family slowly wanders home along a country lane. A moment later, Joanna’s life is changed forever…

On a dark night thirty years later, ex-detective Jackson Brodie finds himself on a train that is both crowded and late. Lost in his thoughts, he suddenly hears a shocking sound…

At the end of a long day, 16-year-old Reggie is looking forward to watching a little TV. Then a terrifying noise shatters her peaceful evening. Luckily, Reggie makes it a point to be prepared for an emergency…

These three lives come together in unexpected and deeply thrilling ways in the latest novel from Kate Atkinson, the critically acclaimed author who Harlan Coben calls “an absolute must-read.”

“As a reader, I was charmed. As a novelist, I was staggered by Kate Atkinson’s narrative wizardry.” — Stephen King

On a hot summer day, Joanna Mason’s family slowly wanders home along a country lane. A moment later, Joanna’s life is changed forever…

On a dark night thirty years later, ex-detective Jackson Brodie finds himself on a train that is both crowded and late. Lost in his thoughts, he suddenly hears a shocking sound…

At the end of a long day, 16-year-old Reggie is looking forward to watching a little TV. Then a terrifying noise shatters her peaceful evening. Luckily, Reggie makes it a point to be prepared for an emergency…

These three lives come together in unexpected and deeply thrilling ways in the latest novel from Kate Atkinson, the critically acclaimed author who Harlan Coben calls “an absolute must-read.”

“As a reader, I was charmed. As a novelist, I was staggered by Kate Atkinson’s narrative wizardry.” — Stephen King

Genre:

-

"As a reader, I was charmed. As a novelist, I was staggered by Kate Atkinson's narrative wizardry."Stephen King, Entertainment Weekly

-

"Uncategorizable, unputdownable, Atkinson's books are like Agatha Christie mysteries that have burst at the seams-they're taut and intricate but also messy and funny and full of life."Time

-

"You don't need to have read the earlier two books to appreciate this one, but I can't think of any reason to deny yourself the delights of all three...The novel satisfies the question in its own title. The answer is: Right here and right now.Laura Miller, Salon

-

"Expertly rendered...It is very much to be hoped that Kate Atkinson keeps this gratifying series going."Janet Maslin, New York Times

-

"Good news lies on every page of this meticulously plotted and affecting thriller."Connie Ogle, Miami Herald

- On Sale

- Jan 11, 2010

- Page Count

- 416 pages

- Publisher

- Back Bay Books

- ISBN-13

- 9780316012836

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use