Promotion

Shop now and save 20% on your back-to-school purchases & get free shipping on orders $45+ Use code: SCHOOL24

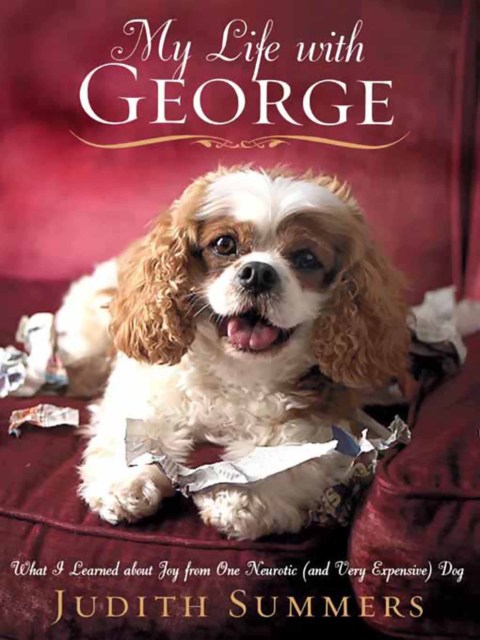

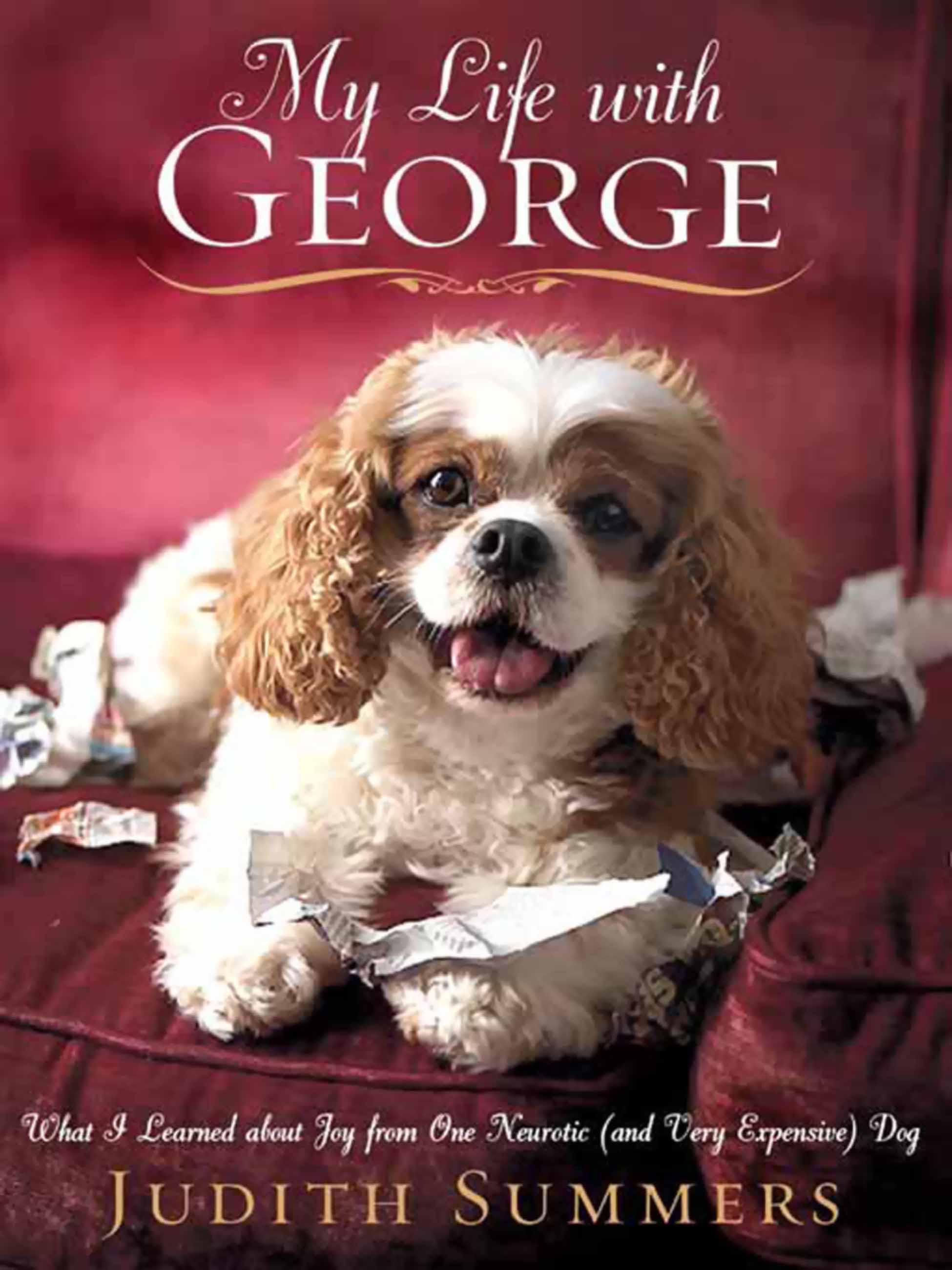

My Life With George

What I Learned About Joy from One Neurotic (And Very Expensive) Dog

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$9.99Price

$12.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $9.99 $12.99 CAD

- Hardcover $35.00 $45.00 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around November 6, 2007. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

When Judith Summers first met George, the Cavalier King Charles Spaniel who would change her life, she and her young son, Joshua, were mourning the deaths of her husband and her father, who had died barely two weeks apart.

It was love at first sight. George was the ultimate upper-class pooch, and seemingly the perfect puppy, brimming with love and joy and complete with “the kind of film-star looks that made strangers stop in the street and coo over him.”

But, as Judith soon discovered, George was as time-consuming as a full-time job and as expensive to run as a Ferrari. Willful, possessive and badly behaved, he refused to eat anything other than organic roast chicken, destroyed her work, and suffered from every allergy and illness under the sun. On top of that, George was horribly accident-prone. Stuff happened to him. His vet bills alone have run to $25,000, and George is still only nine years old!

It wasn’t long before King George ruled the roost in Judith’s home. But even after he drove away one of her suitors, she couldn’t fathom giving him up. Just as his naughtiness was boundless, so was his devotion to her and her son. A foot-warmer on cold nights, a good listener, and a fierce (okay, not so fierce) protector, George was always by their side — and much of the time underfoot.

For anyone who has ever loved an incorrigible pet or known what it was like to lose a loved one, My Life with George is the hilarious and moving account of the impossible but adorable George, and of the wonderful way in which he helped to fill a huge void in the lives of both Judith and her son while driving them absolutely barking mad along the way.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Nov 6, 2007

- Page Count

- 224 pages

- Publisher

- Hachette Books

- ISBN-13

- 9781401389857

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use