Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

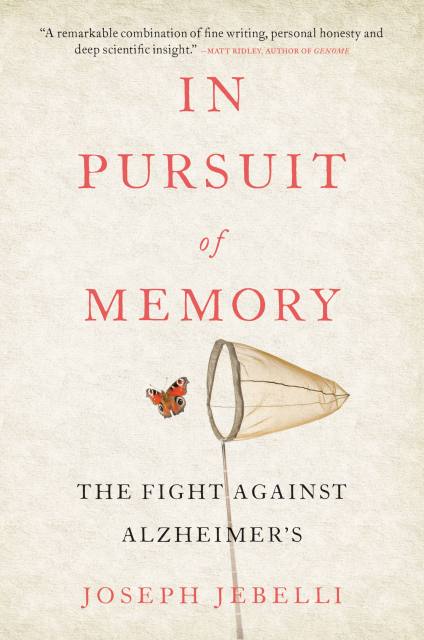

In Pursuit of Memory

The Fight Against Alzheimer's

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$14.99Price

$18.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $14.99 $18.99 CAD

- Hardcover $28.00 $36.50 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

- Trade Paperback $16.99 $22.49 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around October 31, 2017. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

Alzheimer’s is the great global epidemic of our time, affecting millions worldwide — there are more than 5 million people diagnosed in the US alone. And as our population ages, scientists are working against the clock to find a cure.

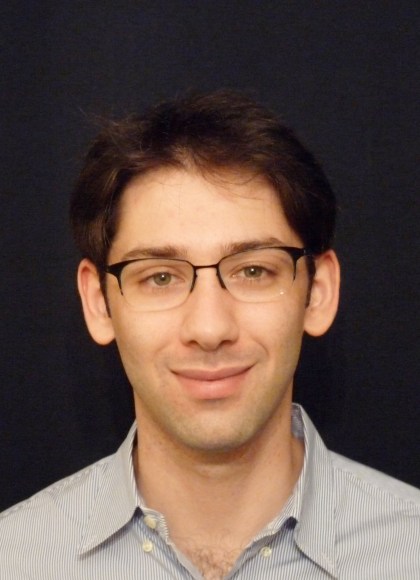

Neuroscientist Joseph Jebelli is among them. His beloved grandfather had Alzheimer’s and now he’s written the book he needed then — a very human history of this frightening disease. But In Pursuit of Memory is also a thrilling scientific detective story that takes you behind the headlines. Jebelli’s quest takes us from nineteenth-century Germany and post-war England, to the jungles of Papua New Guinea and the technological proving grounds of Japan; through America, India, China, Iceland, Sweden, and Colombia. Its heroes are scientists from around the world — many of whom he’s worked with — and the brave patients and families who have changed the way that researchers think about the disease.

This compelling insider’s account shows vividly why Jebelli feels so hopeful about a cure, but also why our best defense in the meantime is to understand the disease. In Pursuit of Memory is a clever, moving, eye-opening guide to the threat one in three of us faces now.

Genre:

-

"An elegant, thorough, compelling and touchingly personal biography of the disease."Wall Street Journal

-

"An overview of Alzheimer's that never once sacrifices the human story for the scientific one. . . . Sensitive, humanizing, and poetic...a masterful overview of the disease."NPR

-

"Jebelli's exploration of the vexed science of Alzheimer's is lucid and emotionally rich in its portrayal of those who investigate the illness and those who endure it."Publishers Weekly (starred review)

-

"An elegant and precise writer, Jebelli follows every lead for a cure with the panache of a detective novelist, giving readers much to hope for despite the devastation Alzheimer's has left in its wake. Based on his meticulous and wide-ranging research, he makes a convincing argument that Alzheimer's will be defeated in the decades to come. Jebelli analyzes every facet of Alzheimer's with personal empathy and scientific rigor, a combination that makes for enthralling reading."Kirkus (starred review)

-

"In Pursuit of Memory is a remarkable combination of fine writing, personal honesty, and deep scientific insight - about a devastating and baffling disease that is becoming all too common. Jebelli weighs up all the evidence and all the theories about Alzheimer's and even allows us a glimpse of optimism about a cure."Matt Ridley

-

"Joseph Jebelli's wonderfully clear, vividly readable and comprehensive survey of the search for a cure . . . The world is closing in on Alzheimer's. There is nowhere left for it to hide."The Times

-

"A moving, sober and forensic study of the past, present and future of Alzheimer's from the point of view of a neurologist who has lived with the disease, at home and in the lab, from a very young age. The story Jebelli tells illustrates the tantalizing mystery of Alzheimer's: it's both highly visible yet agonizingly elusive...a timely analysis [that] might give comfort."Observer

-

"An accessible, diligently researched and well-travelled overview of the disease that is more deadly than cancer. Jebelli poignantly weaves the current science with the tragic stories of affected families, not least his own."Sunday Times

-

"The definitive portrait of Alzheimer's disease - an illness that is rapidly becoming the defining plague of the 21st century."Big Issue

- On Sale

- Oct 31, 2017

- Page Count

- 320 pages

- Publisher

- Little Brown Spark

- ISBN-13

- 9780316398961

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use