Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

Inverting The Pyramid

The History of Soccer Tactics

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$21.99Price

$28.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback (Revised) $21.99 $28.99 CAD

- ebook $11.99 $15.99 CAD

- ebook (Revised) $11.99 $14.99 CAD

- ebook $12.99 $16.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download

- Trade Paperback $24.99 $31.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around August 14, 2018. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

Inverting the Pyramid is a pioneering soccer book that chronicles the evolution of soccer tactics and the lives of the itinerant coaching geniuses who have spread their distinctive styles across the globe.

Through Jonathan Wilson’s brilliant historical detective work we learn how the South Americans shrugged off the British colonial order to add their own finesse to the game; how the Europeans harnessed individual technique and built it into a team structure; how the game once featured five forwards up front, while now a lone striker is not uncommon.

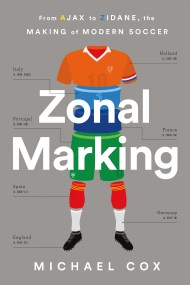

Inverting the Pyramid provides a definitive understanding of the tactical genius of modern-day Barcelona, for the first time showing how their style of play developed from Dutch “Total Football,” which itself was an evolution of the Scottish passing game invented by Queens Park in the 1870s and taken on by Tottenham Hotspur in the 1930s. Inverting the Pyramid has been called the “Big Daddy” (Zonal Marking) of soccer tactics books; it is essential for any coach, fan, player, or fantasy manager of the beautiful game.

Genre:

-

“A wonderful and comprehensive treatment of this important topic. Make sure to secure the revised and updated edition, of course.”Stan Veuge, Senior Fellow, Economic Policy, American Enterprise Institute

- On Sale

- Aug 14, 2018

- Page Count

- 480 pages

- Publisher

- Bold Type Books

- ISBN-13

- 9781568589190

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use