Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

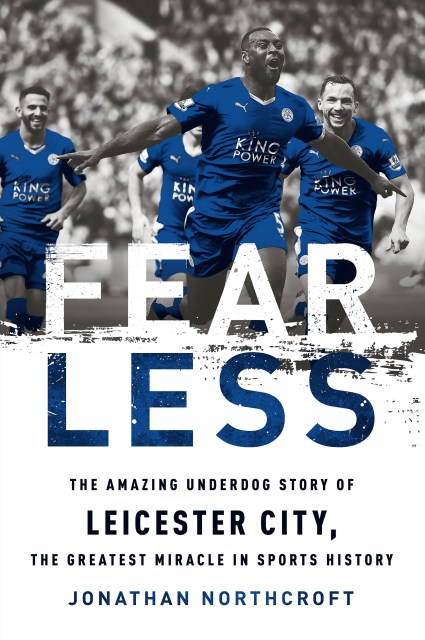

Fearless

The Amazing Underdog Story of Leicester City, the Greatest Miracle in Sports History

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$21.99Price

$28.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $21.99 $28.99 CAD

- ebook $11.99 $14.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around November 22, 2016. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

On March 21, 2015, Leicester City lost their sixth game in eight matches. Without a victory for two months, they were rock bottom of the English Premier League, heading for certain relegation to the lower division, and about to miss out on a once-in-a-lifetime financial bonanza of TV money and opportunity. As usual, London and Manchester would clean up, the rich would get richer, and the hopes of the small, overlooked, multicultural city would sink.

But Leicester started to win. They stayed up; and in the new season they kept on winning. Favorites for relegation, rank outsiders as potential champions (their 5000 — 1 odds were the longest in the world for any major sporting event), their entire squad had been assembled for less than the cost of a single player for Manchester City. Still, they beat Manchester City and Liverpool, Tottenham and Chelsea: the most incredible cast of written-offs, grafters, misfits, and journeymen came together for the season of their lives.

This is the story every underdog dreams of, every small town with a much larger, more affluent neighbor hopes for, and a triumph that defies logic and expectation.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Nov 22, 2016

- Page Count

- 352 pages

- Publisher

- Bold Type Books

- ISBN-13

- 9781568589824

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use