Promotion

Shop now and save 20% on your back-to-school purchases & get free shipping on orders $45+ Use code: SCHOOL24

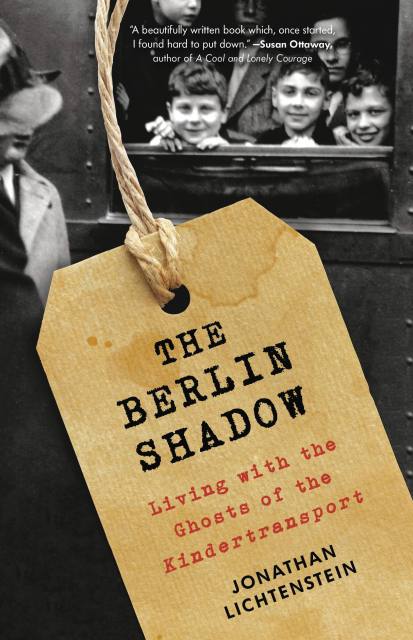

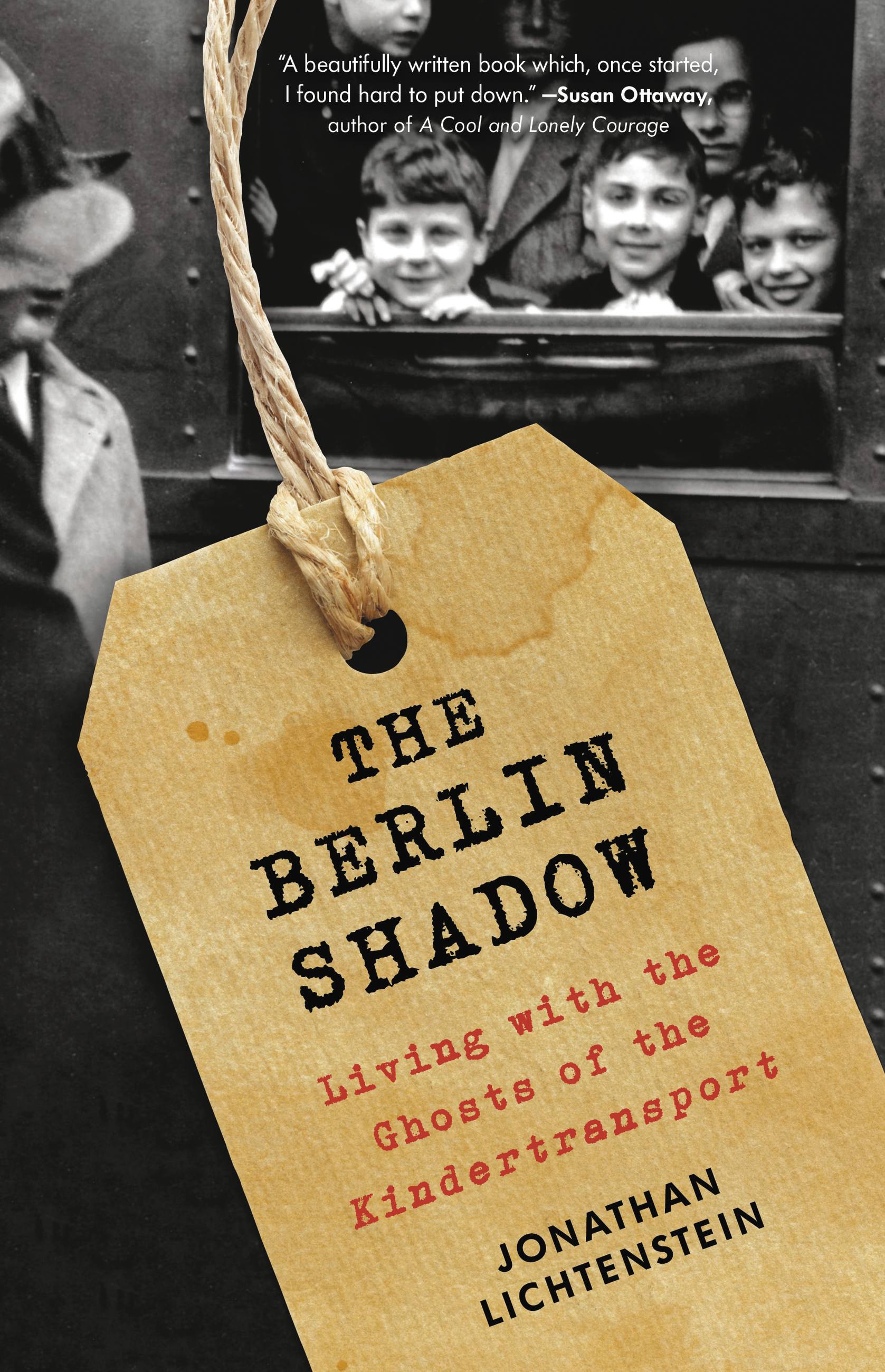

The Berlin Shadow

Living with the Ghosts of the Kindertransport

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$14.99Price

$19.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $14.99 $19.99 CAD

- Hardcover $28.00 $35.00 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around December 15, 2020. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

A deeply moving memoir that confronts the defining trauma of the twentieth century, and its effects on a father and son.

In 1939, Jonathan Lichtenstein's father Hans escaped Nazi-occupied Berlin as a child refugee on the Kindertransport. Almost every member of his family died after Kristallnacht, and, upon arriving in England to make his way in the world alone, Hans turned his back on his German Jewish culture.

Growing up in post-war rural Wales where the conflict was never spoken of, Jonathan and his siblings were at a loss to understand their father's relentless drive and sometimes eccentric behavior. As Hans enters old age, he and Jonathan set out to retrace his journey back to Berlin.

Written with tenderness and grace, The Berlin Shadow is a highly compelling story about time, trauma, family, and a father and son's attempt to emerge from the shadows of history.

In 1939, Jonathan Lichtenstein's father Hans escaped Nazi-occupied Berlin as a child refugee on the Kindertransport. Almost every member of his family died after Kristallnacht, and, upon arriving in England to make his way in the world alone, Hans turned his back on his German Jewish culture.

Growing up in post-war rural Wales where the conflict was never spoken of, Jonathan and his siblings were at a loss to understand their father's relentless drive and sometimes eccentric behavior. As Hans enters old age, he and Jonathan set out to retrace his journey back to Berlin.

Written with tenderness and grace, The Berlin Shadow is a highly compelling story about time, trauma, family, and a father and son's attempt to emerge from the shadows of history.

-

"The Berlin Shadow is a haunting account of a journey of remembrance, discovery, and forgiveness. A beautifully written book which, once started, I found hard to put down."Susan Ottaway, author of A Cool and Lonely Courage

-

“This is indeed a memoir, an effort to remember--and to unremember. Two damaged men—father and son—attempt to discover the origins of their own tense relationship, pockmarked by years of misunderstanding. Beginning in Wales (with a marvelous sensitivity about that province) then proceeding to Germany, from where Hans Lichtenstein, the father, had been shipped out to Great Britain for his safety in 1939, Jonathan Lichtenstein ties together delicately two of the most significant aspects of a narrative of memory: space and time. The Berlin Shadow details with an emphatic honesty the traumas visited on generations of Jews who survived the war, only to find themselves, once again, marginalized, unwanted, and despised. Hans needs to relive those last few years of freedom in Berlin and his adult son must untangle the skein of wounded feelings imprinted on him by a protective, but exigent father. Many will read The Berlin Shadow in one sitting, for the experiences of the two protagonists will demand a moral attention; an interrupted reading seems almost like a sacrilege.”Ronald C. Rosbottom, professor at Amherst College, and author of When Paris Went Dark and Sudden Courage

-

“If you read one book this year, make it The Berlin Shadow. It is deeply moving, utterly compelling, touchingly funny and so beautifully written that at times it takes your breath away. It taught me so much about love, life, memory and time that I feel I have grown wiser and more appreciative of my own life because of it. Lichtenstein has a rare gift that I hope will be shared with readers all over the world. I cannot praise this book enough. Every adjective I come up with falls short. It’s beautiful.”Santa Montefiore, author of The Secret Hours

- On Sale

- Dec 15, 2020

- Page Count

- 320 pages

- Publisher

- Little Brown Spark

- ISBN-13

- 9780316540995

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use