Promotion

Sign up for our newsletters to receive 20% off! Shop now. Exclusions apply.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

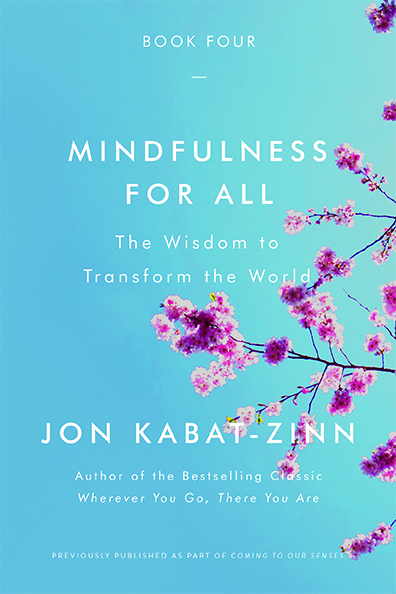

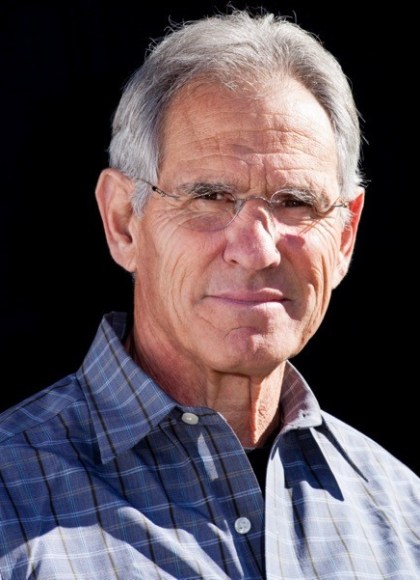

Mindfulness for All

The Wisdom to Transform the World

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$19.99Price

$25.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $19.99 $25.99 CAD

- ebook $9.99 $12.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around February 5, 2019. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

Now, Coming to Our Senses is being repackaged into 4 smaller books, each focusing on a different aspect of mindfulness, and each with a new foreword written by the author. In the fourth of these books, Mindfulness for All (which was originally published as Part VII and Part VIII of Coming to Our Senses), Kabat-Zinn focuses on how mindfulness really can be a tool to transform the world–explaining how democracy thrives in a mindful context, and why mindfulness is a vital tool for both personal and global understanding and action in these tumultuous times. By “coming to our senses”–both literally and metaphorically–we can become more compassionate, more embodied, more aware human beings, and in the process, contribute to the healing of the body politic as well as our own lives in ways both little and big.

- On Sale

- Feb 5, 2019

- Page Count

- 192 pages

- Publisher

- Hachette Books

- ISBN-13

- 9780316411776

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use