Promotion

Sign up for our newsletters to receive 20% off! Shop now. Exclusions apply.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

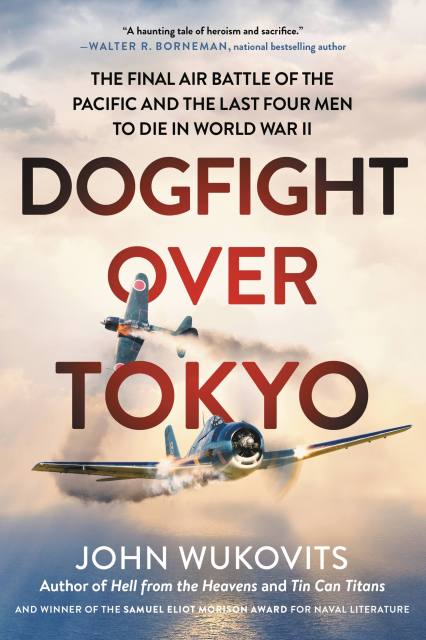

Dogfight over Tokyo

The Final Air Battle of the Pacific and the Last Four Men to Die in World War II

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$14.99Price

$19.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $14.99 $19.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

- Trade Paperback $17.99 $22.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around August 27, 2019. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

When Billy Hobbs and his fellow Hellcat aviators from Air Group 88 lifted off from the venerable Navy carrier USS Yorktown early on the morning of August 15, 1945, they had no idea they were about to carry out the final air mission of World War II. Two hours later, Yorktown received word from Admiral Nimitz that the war had ended and that all offensive operations should cease. As they were turning back, twenty Japanese planes suddenly dove from the sky above them and began a ferocious attack. Four American pilots never returned—men who had lifted off from the carrier in wartime but were shot down during peacetime.

Drawing on participant letters, diaries, and interviews, newspaper and radio accounts, and previously untapped archival records, historian and prolific author of acclaimed Pacific theater books, including Tin Can Titans and Hell from the Heavens, John Wukovits tells the story of Air Group 88's pilots and crew through their eyes. Dogfight over Tokyo is written in the same riveting, edge-of-your-seat style that has made Wukovits's previous books so successful. This is a stirring, one-of-a-kind tale of naval encounters and the last dogfight of the war—a story that is both inspirational and tragic.

-

"What we know of war usually comes from survivors. This book is about four young flyers who didn't come back. Those who die give up all that they have, all their hopes and dreams, all the infinite potential life offers. Wukovits captures that tragedy in a powerful way. Superb."Stephen Coonts, New York Times bestselling author

-

"But for one tragic hour, they would have returned safely to the loved ones who worried over them so much. Instead, four Navy fighter pilots became the final combat casualties of World War II. As he did in Tin Can Titans and Hell from the Heavens, John Wukovits skillfully entwines the personal stories of young men at war with the horrors of the larger conflict. Dogfight Over Tokyo is a haunting tale of heroism and sacrifice and the continuing agony of those left to grieve."Walter R. Borneman, bestselling author of Brothers Down: Pearl Harbor and the Fate of the Many Brothers aboard the USS Arizona

-

"In this meticulously researched work, John Wukovits provides rare personal insight to the aviators who fought the U.S. Navy's LAST major combat of World War II-and those supporting them on the home front. If it's true that no war truly ends while some still remember it, then Dogfight Over Tokyo extends our national memory of those who brought the world's greatest conflagration to a joyous, painful, and bittersweet end."Barrett Tillman, author of Whirlwind and On Wave and Wing

-

"An expertly researched addition to the military history/biography genre"Kirkus Reviews

- On Sale

- Aug 27, 2019

- Page Count

- 336 pages

- Publisher

- Da Capo Press

- ISBN-13

- 9780306922046

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use