Promotion

Save 20% off + free shipping on orders $45+ Use code: DAD24 Shop Now.

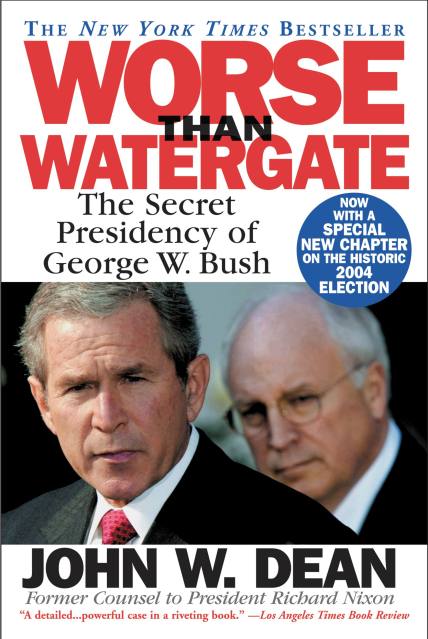

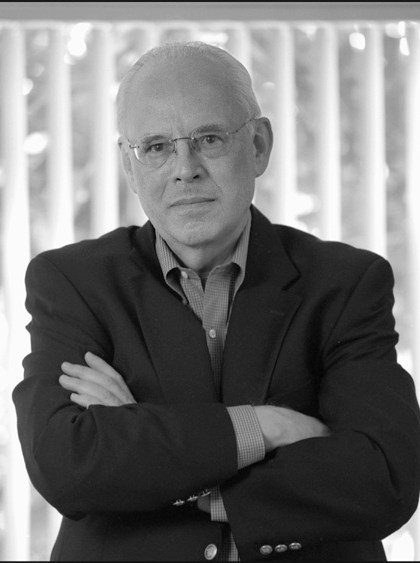

Worse Than Watergate

The Secret Presidency of George W. Bush

Contributors

By John W. Dean

Formats and Prices

Price

$9.99Price

$12.99 CADFormat

Format:

ebook $9.99 $12.99 CADThis item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around April 6, 2004. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

Former White House counsel and bestselling author John Dean reveals how the Bush White House has set America back decades — employing a worldview and tactics of deception that he claims will do more damage to the nation than Nixon at his worst.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Apr 6, 2004

- Page Count

- 272 pages

- Publisher

- Little, Brown and Company

- ISBN-13

- 9780759510388

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use