By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

The Hummingbird Handbook

Everything You Need to Know about These Fascinating Birds

Contributors

By John Shewey

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Apr 27, 2021

- Page Count

- 240 pages

- Publisher

- Timber Press

- ISBN-13

- 9781643260181

Price

$24.99Price

$32.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $24.99 $32.99 CAD

- ebook $11.99 $15.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around April 27, 2021. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

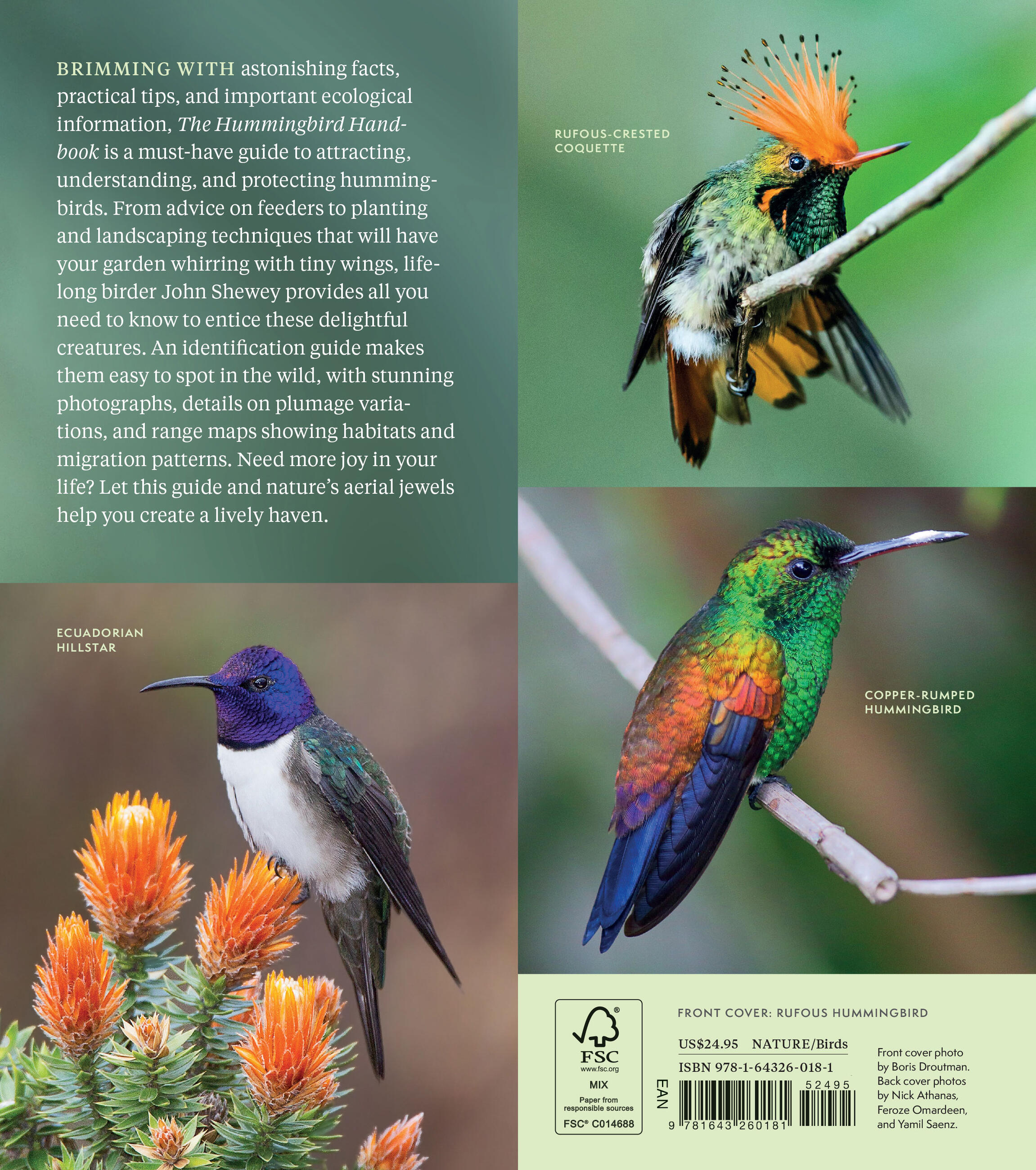

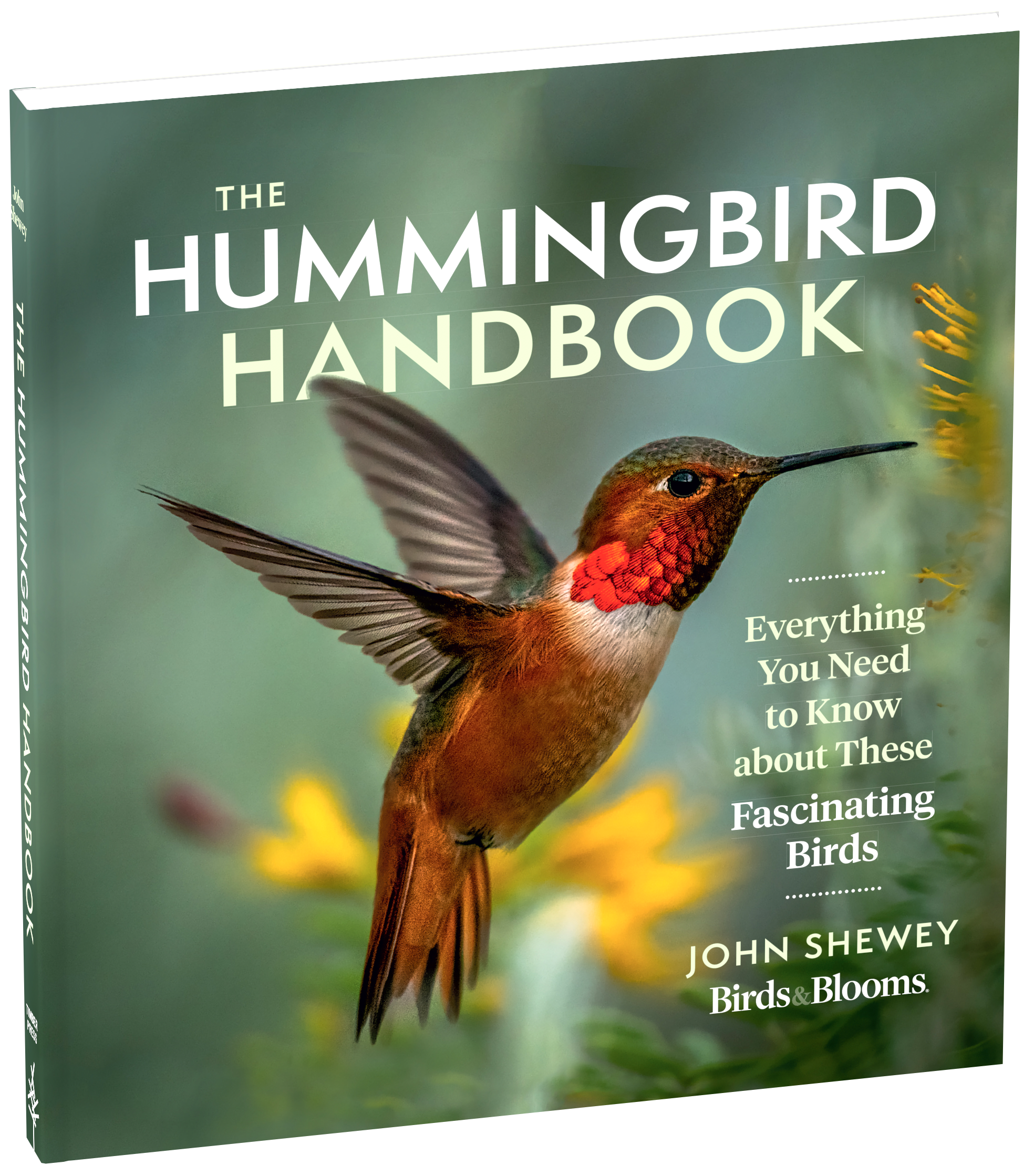

This fascinating guide book is a must-have for anyone looking to attract, understand, and protect hummingbirds.

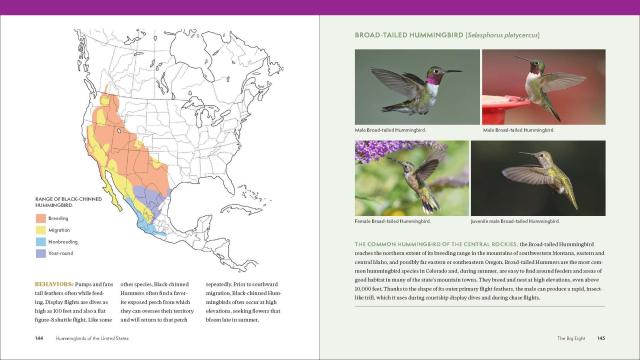

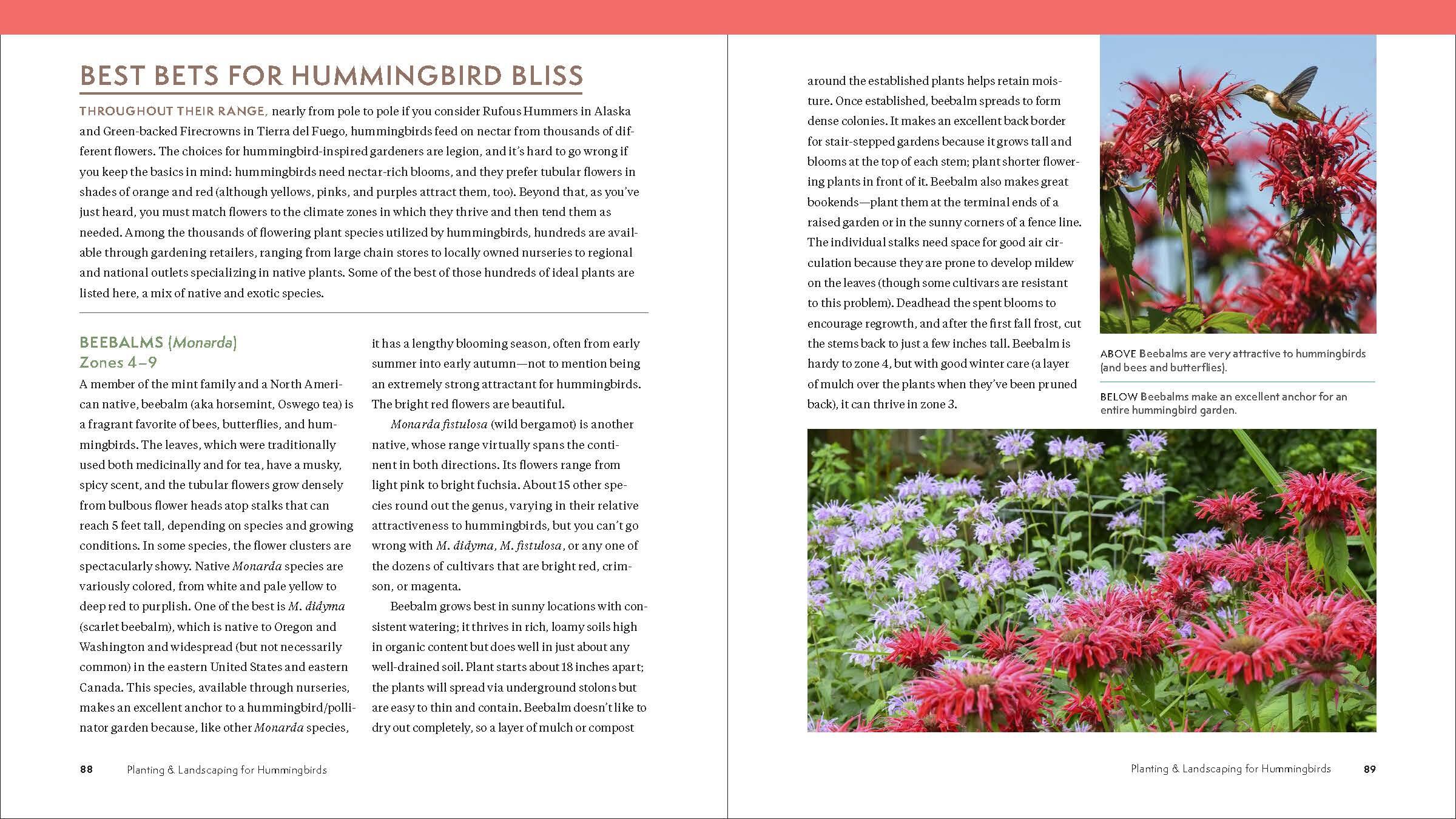

Hummingbirds inspire an unmistakable sense of devotion and awe among bird lovers. From advice on feeders to planting and landscaping techniques that will have your garden whirring with tiny wings, lifelong birder John Shewey provides all you need to know to entice these delightful creatures. An identification guide makes them easy to spot in the wild, with stunning photographs, details on plumage variations, and range maps showing habitats and migration patterns.

“Captures the spirit and allure of these captivating birds in every fascinating fact, historical tidbit, amusing anecdote, species profile and plant pick.” —Birds & Blooms

Genre:

-

“This overview offers hummer trivia, mythology, and new discoveries… Vivid, full-color photos appear on almost every page, and other visuals include maps and multi-photo comparison charts... Shewey, a birder and professional outdoor photographer, admits to being fascinated by hummingbirds. After seeing this book, readers will be too.” —Booklist

“John Shewey captures the spirit and allure of these captivating birds in every fascinating fact, historical tidbit, amusing anecdote, species profile and plant pick.” —Birds Blooms

“The latest addition to the Trochilidae canon… yes, more please.” —Birdwatching

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use