By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

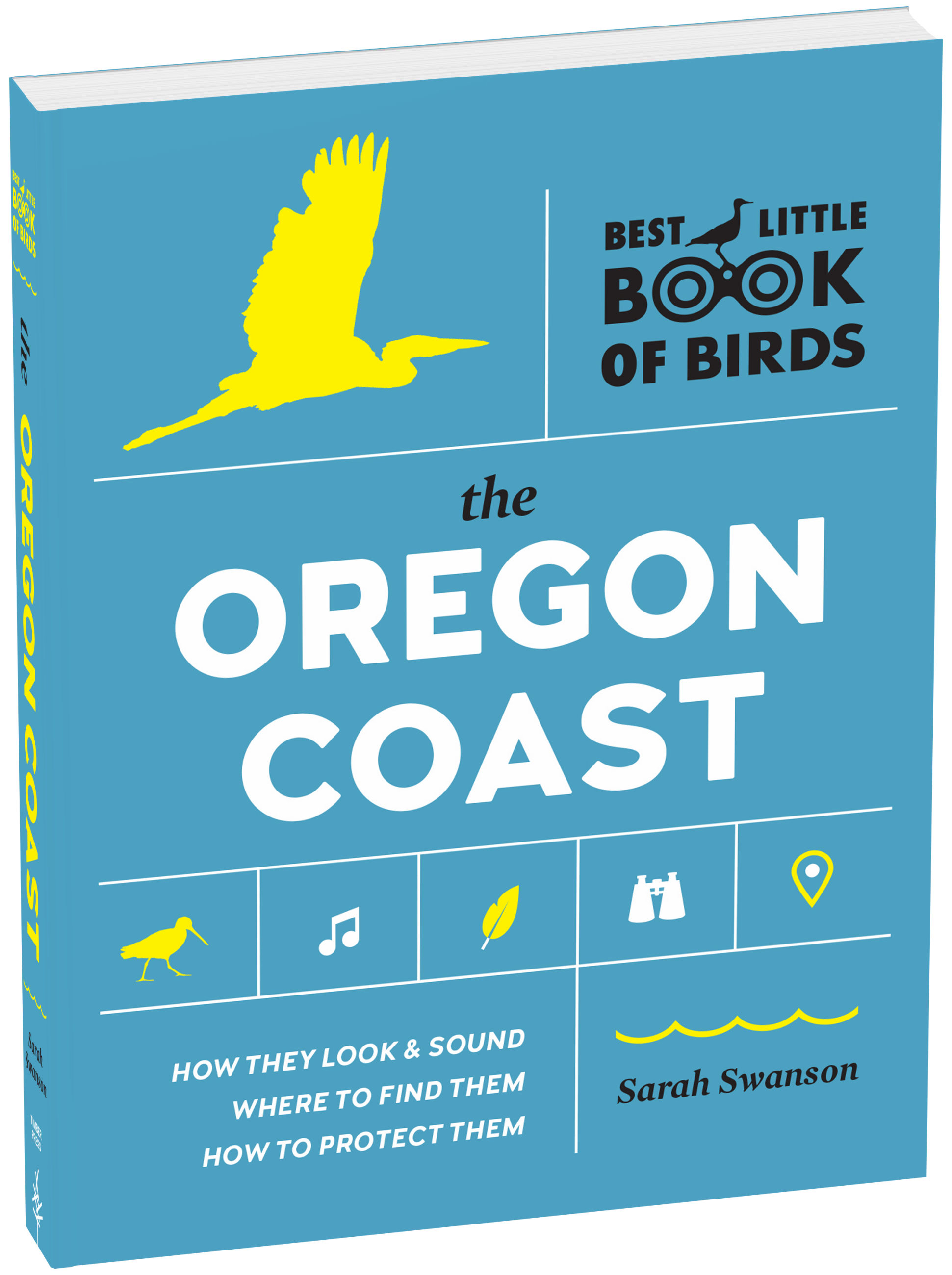

Birds of the Oregon Coast

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Oct 11, 2022

- Page Count

- 304 pages

- Publisher

- Timber Press

- ISBN-13

- 9781643260600

Price

$16.99Price

$22.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $16.99 $22.99 CAD

- ebook $10.99 $13.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around October 11, 2022. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

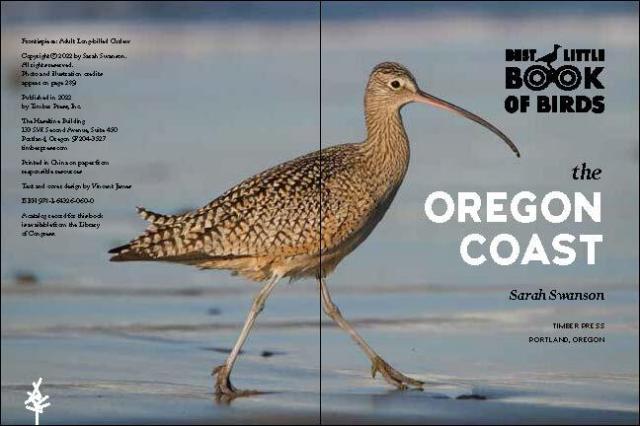

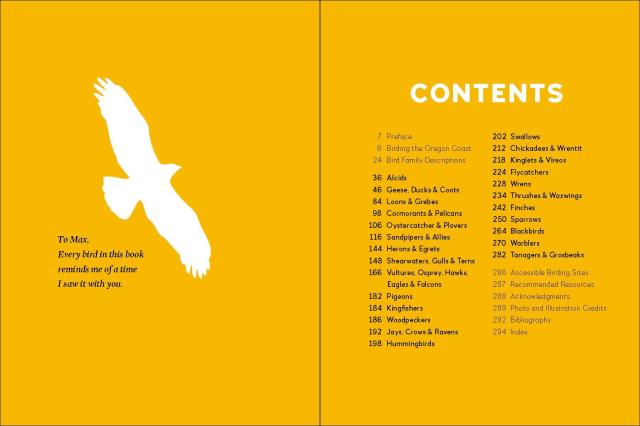

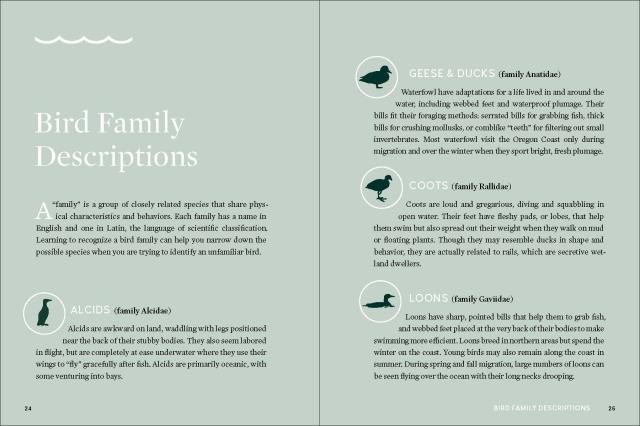

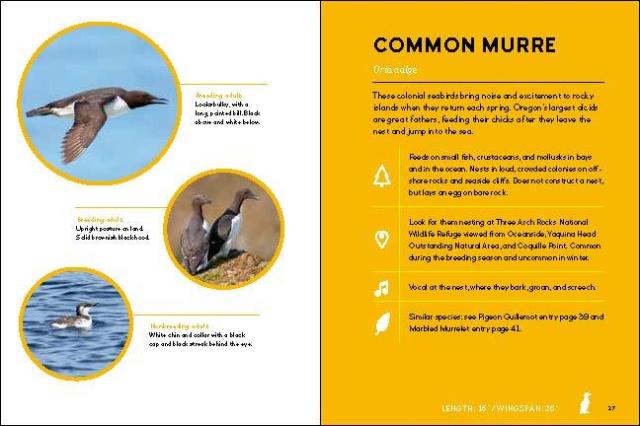

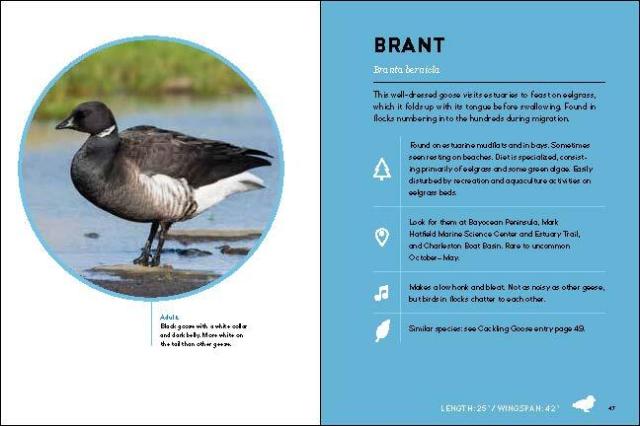

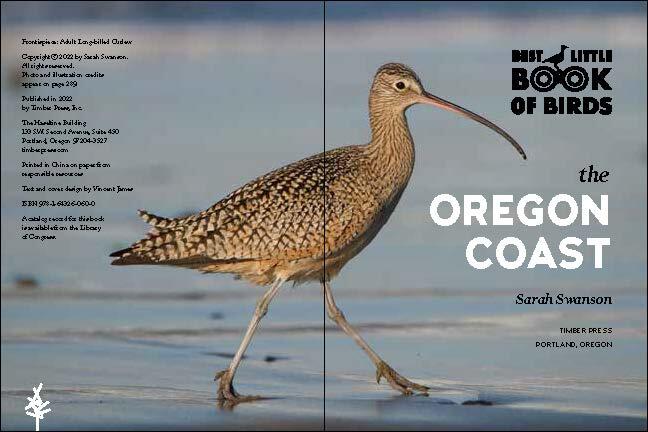

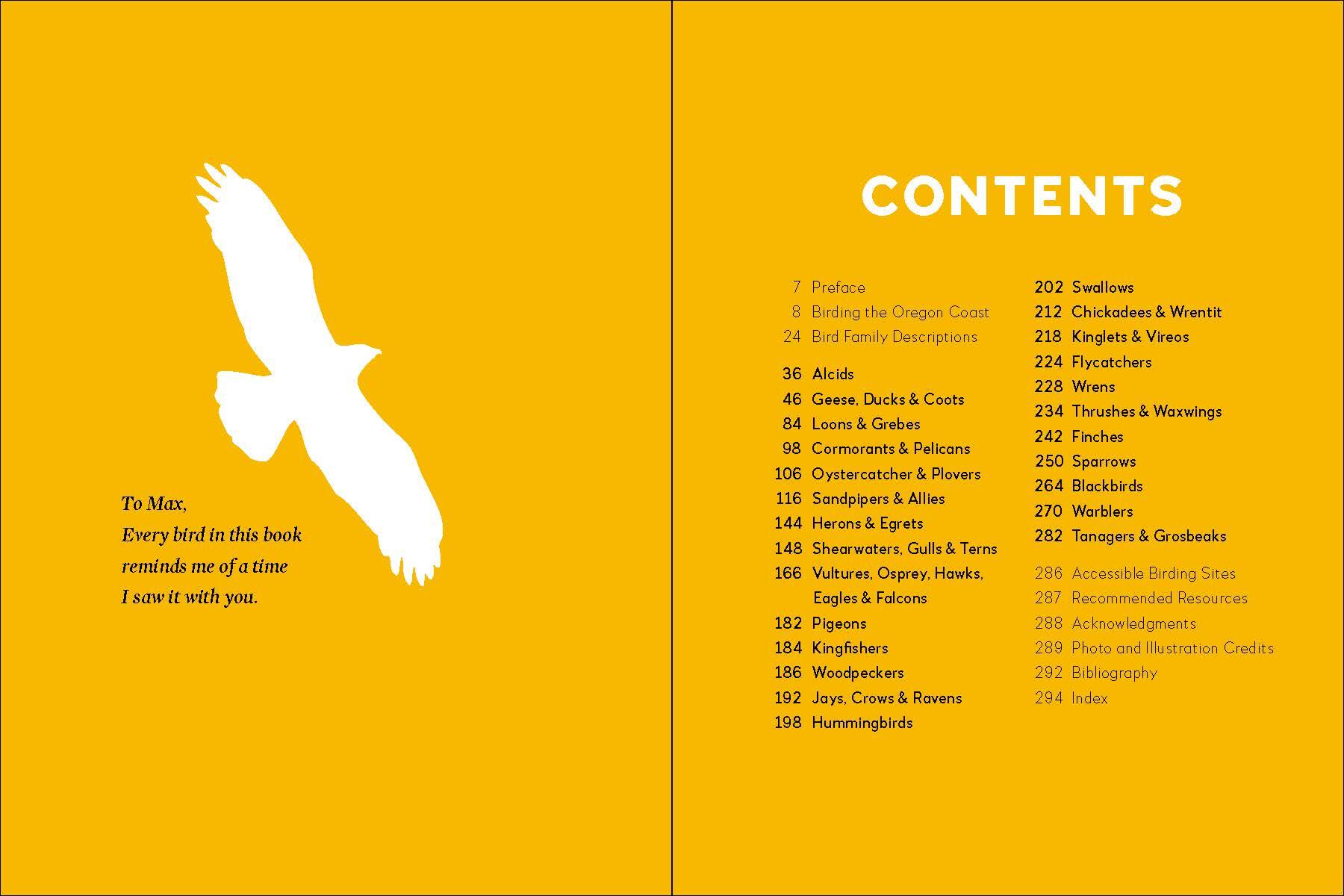

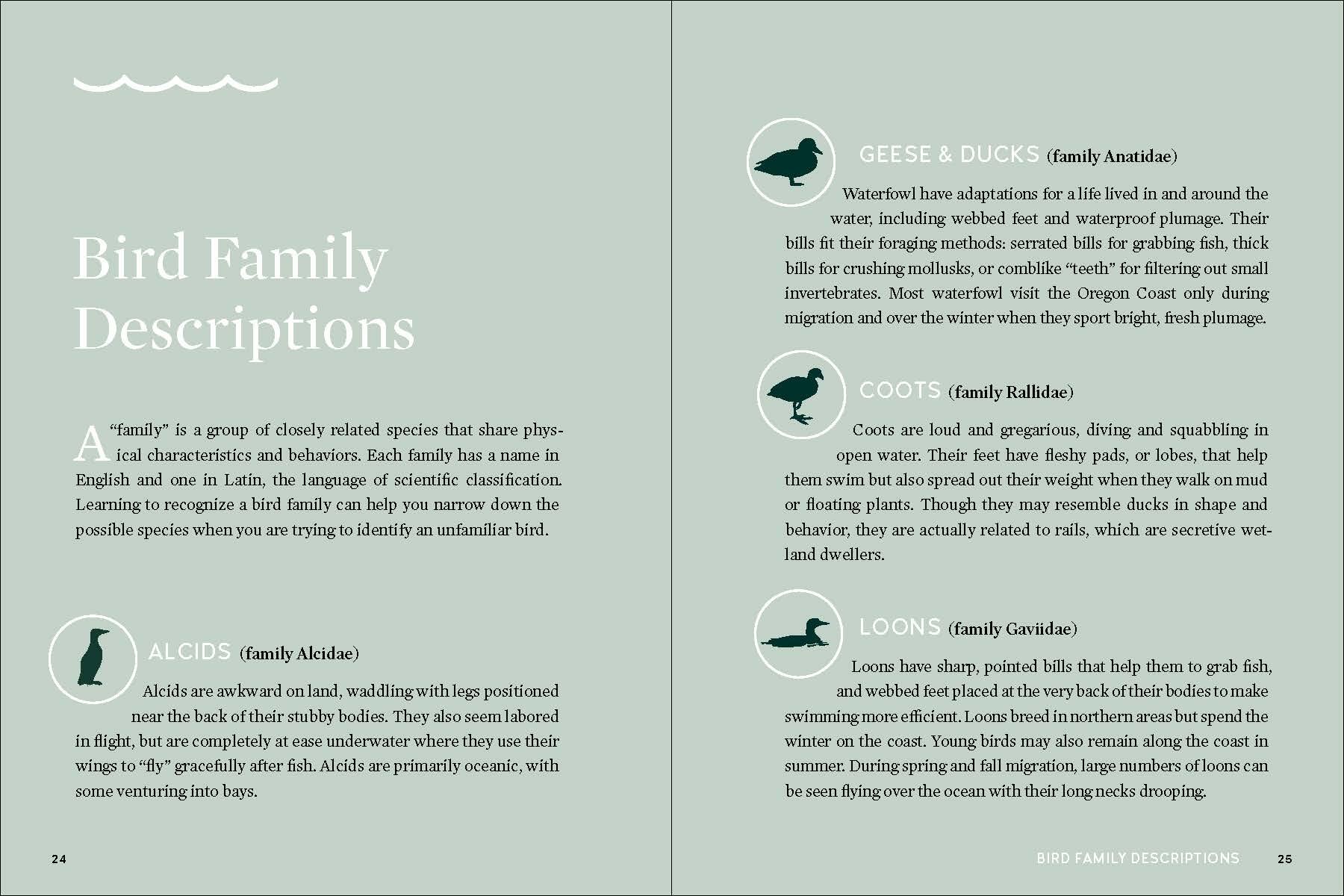

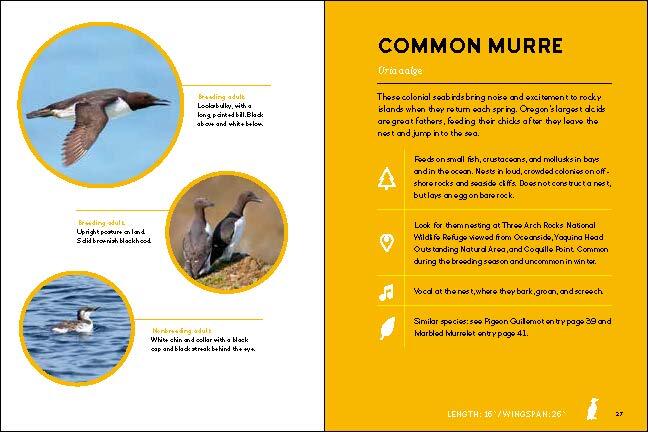

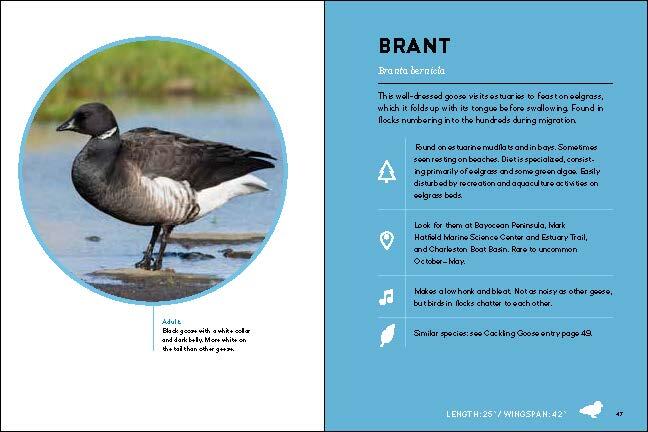

Oregon’s coast is teeming with scores of beautiful birds, and the Birds of the Oregon Coast will help you find them. From regal ospreys and iconic eagles to frenetic sandpipers and colorful kingfishers, this easy-to-use book will help you identify more than 100 commonly occurring birds that help make the Oregon coast the natural wonder that it is. An emphasis on best practices and habitat sustainability help empower conservation and ensure that birding on the coast will be possible for years to come. Perfect for budding and experienced birders alike, this sleek and compact guide is the ideal travel companion for every trip to the coast.

Genre:

Series:

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use