Promotion

Sign up for our newsletters to receive 20% off! Shop now. Exclusions apply.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

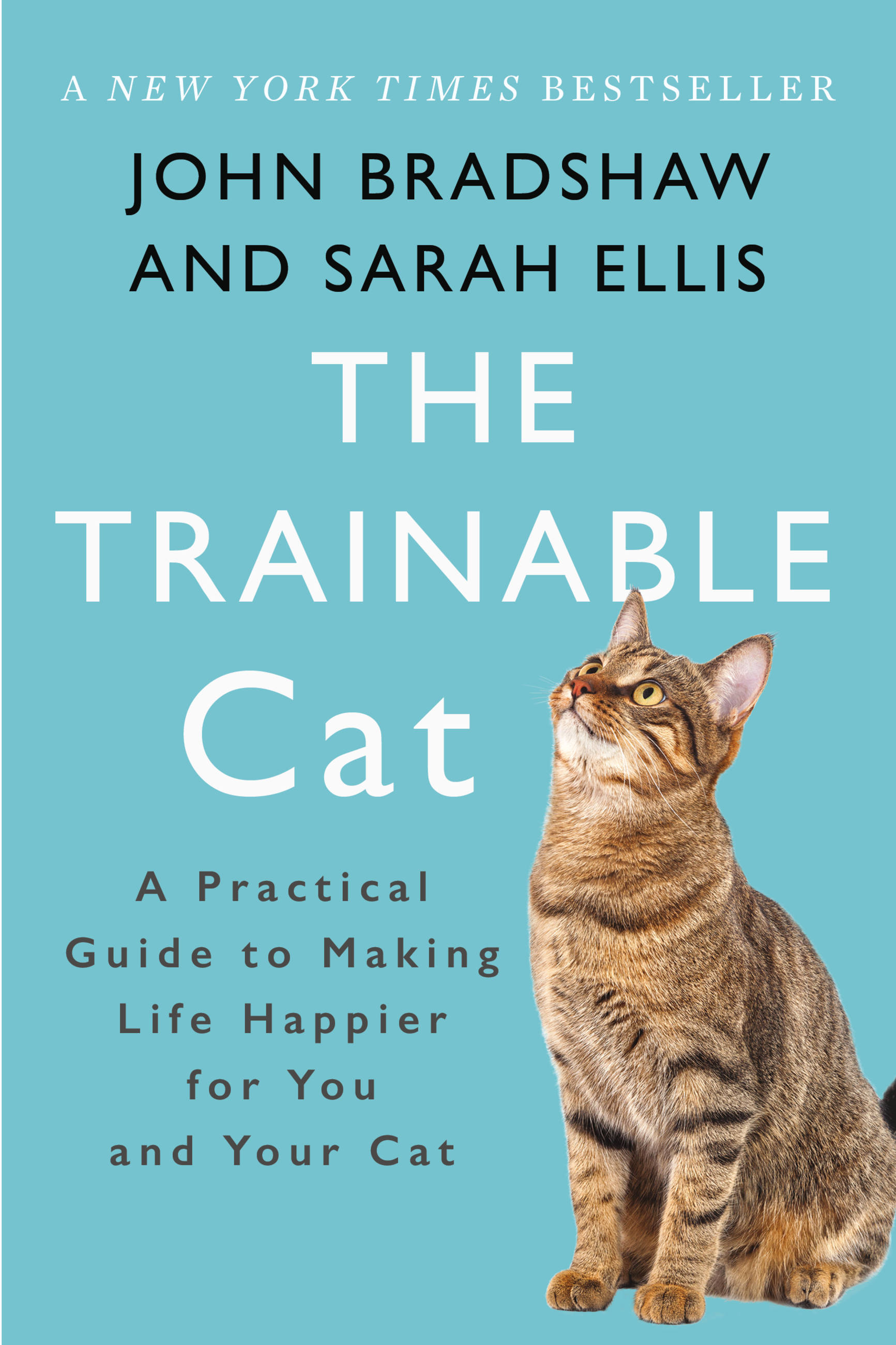

The Trainable Cat

A Practical Guide to Making Life Happier for You and Your Cat

Contributors

By Sarah Ellis

Formats and Prices

Price

$13.99Price

$17.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $13.99 $17.99 CAD

- Trade Paperback $19.99 $25.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around September 13, 2016. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

We often assume that cats can’t be trained, and don’t need to be. But in The Trainable Cat, bestselling anthrozoologist John Bradshaw and cat expert Sarah Ellis show that cats absolutely must be trained in order to enrich the bond between pet and owner. Full of training tips and exercises — from introducing your cat to a new baby to helping them deal with visits to the vet — The Trainable Cat is the essential cat bible for cat owners and lovers.

“I doubt you’ll find a more well-informed or scientific book on cats that better shows you how feline thinking works.” — Times (UK)

Genre:

- On Sale

- Sep 13, 2016

- Page Count

- 352 pages

- Publisher

- Basic Books

- ISBN-13

- 9780465096497

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use