Promotion

Use code FALL24 for 20% off sitewide!

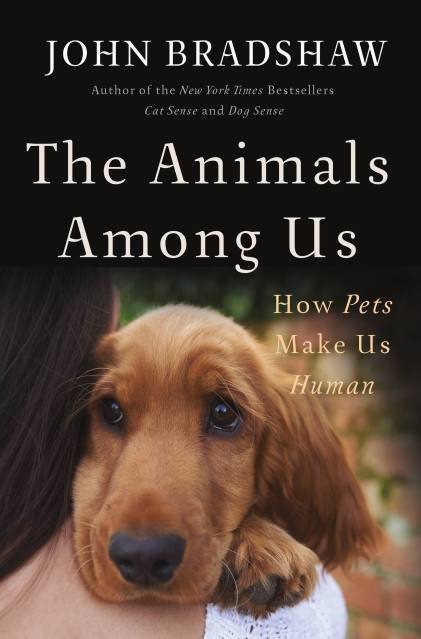

The Animals Among Us

How Pets Make Us Human

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$15.99Price

$20.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $15.99 $20.99 CAD

- Hardcover $28.00 $36.50 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around October 31, 2017. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

Historically, we relied on our pets to herd livestock, guard homes, and catch pests. But most of us don’t need animals to do these things anymore. Pets have never been less necessary. And yet, pet ownership has never been more common than it is today: half of American households contain a cat, a dog, or both. Why are pets still around?

In The Animals Among Us, John Bradshaw, one of the world’s leading authorities on the relationship between humans and animals, argues that pet ownership is actually an intrinsic part of human nature. He explains how our empathy with animals evolved into a desire for pets, why we still welcome them into our families, and why we mourn them so deeply when they die.

Drawing on the latest research in biology and psychology, as well as fields as diverse as robotics and musicology, The Animals Among Us is a surprising and affectionate history of humanity’s best friends.

- On Sale

- Oct 31, 2017

- Page Count

- 384 pages

- Publisher

- Basic Books

- ISBN-13

- 9780465093151

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use