Promotion

Shop now and save 20% on your back-to-school purchases & get free shipping on orders $45+ Use code: SCHOOL24

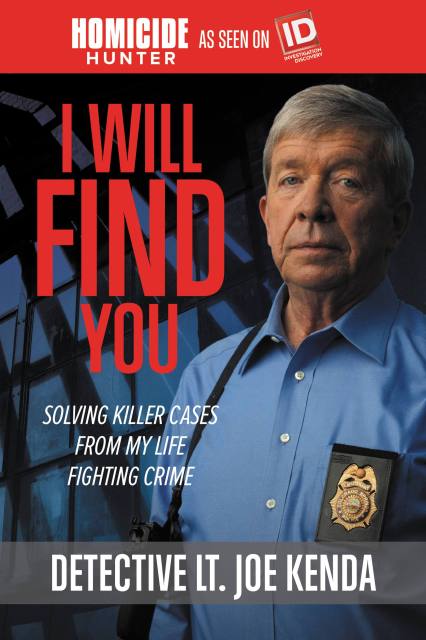

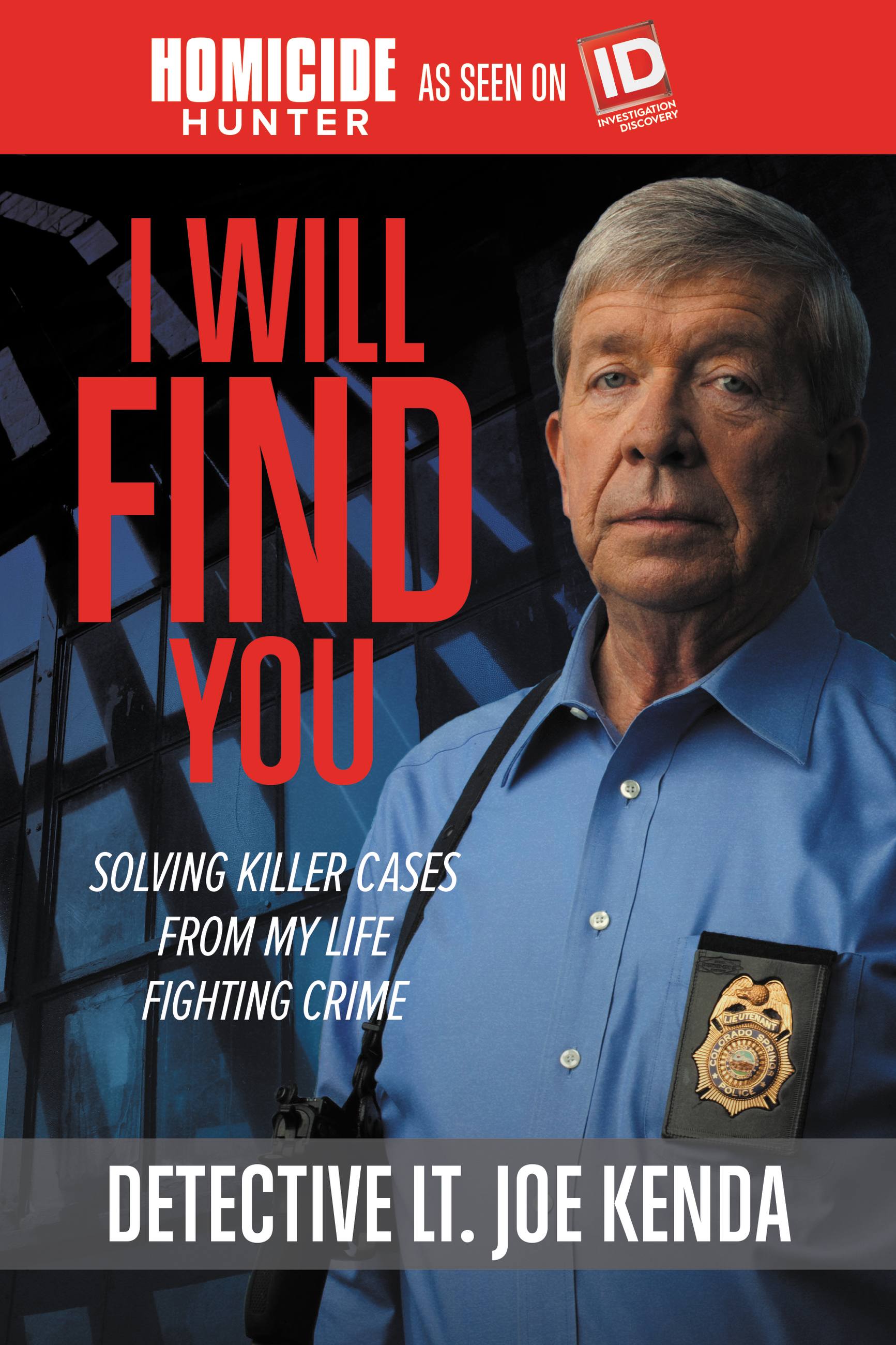

I Will Find You

Solving Killer Cases from My Life Fighting Crime

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$11.99Price

$14.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $11.99 $14.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $24.99

- Trade Paperback $17.99 $22.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around September 26, 2017. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

Are you horrified yet fascinated by abhorrent murders? Do you crave to know the gory details of these crimes, and do you seek comfort in the solving of the most gruesome?

In I Will Find You, the star of Homicide Hunter: Lt. Joe Kenda shares his deepest, darkest, and never-before-revealed case files from his two decades as a homicide detective and reminds us that crimes like these are very real and can happen even in our own backyards.

Gruesome, macabre, and complex cases.

Joe Kenda investigated 387 murder cases during his 23 years with the Colorado Springs Police Department and solved almost all of them. And he is ready to detail the cases that are too gruesome to air on television, cases that still haunt him, and the few cases where the killer got away. These cases are horrifyingly real, and the detail is so mesmerizing you won’t be able to look away.

The tales in I Will Find You will shock you like the best horror stories-divulging insights into the actions, motivations, and proclivities of nature’s most dangerous species.

Don’t mind the blood.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Sep 26, 2017

- Page Count

- 288 pages

- Publisher

- Center Street

- ISBN-13

- 9781478922407

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use