By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

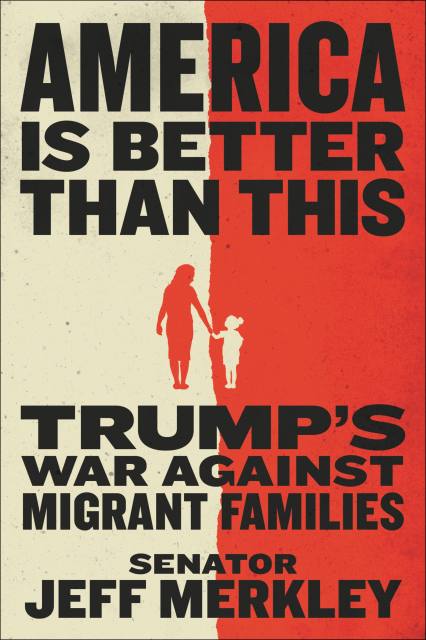

America Is Better Than This

Trump's War Against Migrant Families

Contributors

By Jeff Merkley

Formats and Prices

Price

$13.99Price

$17.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $13.99 $17.99 CAD

- Hardcover $27.00 $35.50 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

- Trade Paperback $13.99

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around August 20, 2019. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

Jeff Merkley couldn’t believe his eyes. He never dreamed the United States could treat vulnerable young families with such calculated brutality. Few had witnessed what Merkley discovered just by showing up at the border and demanding to see what was going on behind closed doors.

Contrary to the official stories and soothing videos, he found mothers and children, newborn babies and infants, stranded for days on border bridges in blistering heat or locked up in ice-cold holding pens. There were nearly 1,500 boys jammed into a former Walmart, a child tent prison in the desert with almost 3,000 boys and girls, and children struggling to survive in gang-filled Mexican border towns after they were blocked from seeking asylum in the United States.

Worst of all, there were the children ripped out of their parents’ arms and sorted into cages in some profoundly warped attempt to discourage migration.

This was how the Trump administration treated the child victims of unspeakable violence that had driven them from their homes: as pawns in a power play rather than as humans worthy of respect and dignity.

It was Merkley’s visits — captured live on viral video — that triggered worldwide outrage at the forced separation of children from their parents. Just by taking an interest — by caring about the people legally claiming asylum at America’s borders — Merkley helped expose the Trump administration’s war on migrant families. Along the way, he helped turn the tide against some of its worst excesses.

AMERICA IS BETTER THAN THIS tells the inside story of how one senator, with no background as an immigration activist, became a leading advocate for reform of the brutal policies that have created a humanitarian crisis on the southern U.S. border. It represents the heartfelt and candid voice of a concerned American who believes his country stands for something far bigger and better.

-

"Senator Jeff Merkley has led the fight to expose President Trump's inhumane family separation policy and to reunite families torn apart at the border. America is Better Than This is a powerful reminder of our moral duty to speak out and fight back."Senator Elizabeth Warren

-

"Senator Jeff Merkley bears powerful witness to the trauma faced by migrant families on America's border, and delivers an urgent challenge to every reader to fight for justice, respect, and dignity for all."p.p1 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px; line-height: 17.0px; font: 14.7px Helvetica; color: #323130; -webkit-text-stroke: #323130; background-color: #ffffff}span.s1 {font-kerning: none}Neal Keny-Guyer, CEO of Mercy Corps

- On Sale

- Aug 20, 2019

- Page Count

- 240 pages

- Publisher

- Twelve

- ISBN-13

- 9781538734186

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use