Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

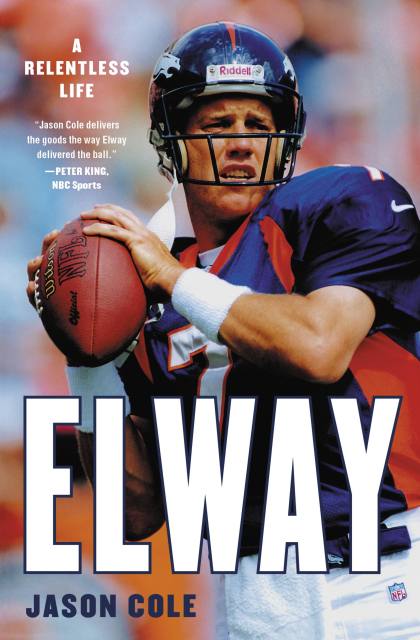

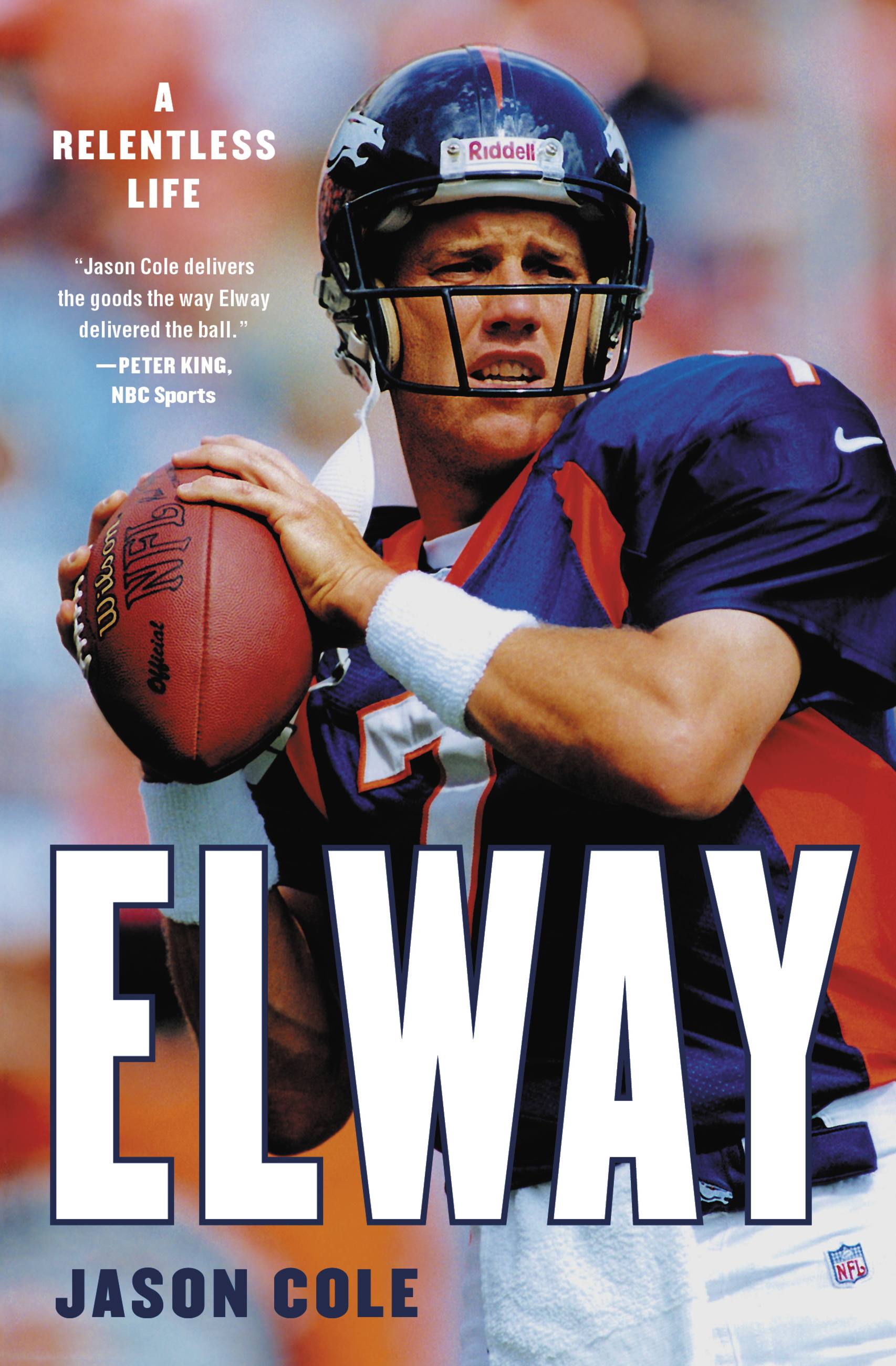

Elway

A Relentless Life

Contributors

By Jason Cole

Formats and Prices

Price

$18.99Price

$23.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $18.99 $23.99 CAD

- ebook $11.99 $15.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around November 9, 2021. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

John Elway's historic moments are known by two-word phrases. He was at the center of the wildest play in college football history, simply known as "The Play." Before he signed a pro contract, there was "The Trade." His NFL career included "The Drive" and "The Fumble," and, of course, "The Helicopter," one of the most iconic highlights in Super Bowl lore. There are so many memorable comeback victories and heroic plays that people have to make lists rather than consider Elway in the context of any singular event.

Yet Elway's story is filled with one challenge after another. At Stanford, he never played in a Bowl game. He was ripped for being petulant after refusing to sign with the Baltimore Colts when he was drafted No. 1 overall, and later for his failure to get along with coach Dan Reeves. Over the first 10 years of his career, Elway led Denver to three Super Bowls, but lost in progressively worse fashion each time. Finally, after fifteen years of perseverance, Elway led the Broncos to back-to-back championships, including the biggest upset in Super Bowl history. Elway won the MVP award in his final Super Bowl and then walked away from the game.

Within four years, Elway's father and twin sister both died, and he went through a difficult divorce. Reeling in his post-retirement, he returned to football . . . at the bottom, running the Colorado Crush of the Arena Football League. He waited more than a decade to return to his beloved Broncos. While many people doubted him initially, Elway navigated the Broncos through massive changes and to victory in Super Bowl 50, making Elway the rare Hall of Famer to win a title both on and off the field. Elway has put his passion for competition on display in a way that only a handful of other NFL greats have ever done, and Elway is the most complete look at one of the most accomplished legends in the history of American sports.

Genre:

-

"John Elway is one of the most well-documented figures in the 37 years I've covered football, and it's a tribute to Jason Cole's rich reporting that this book is filled with stuff I never knew. Elway the pitcher versus Strawberry the slugger in the Los Angeles high school baseball championship ... Living in a Belushi-like Animal House at Stanford ... How barely remembered Denver owner Edgar Kaiser made the Elway trade ... Riveting details of Elway's spats with Dan Reeves ... And as Broncos GM years later, wisely slow-playing his pursuit of Peyton Manning. This, then, is a particularly valuable story of the life and times of a great player, in and out of football. Jason Cole delivers the goods the way Elway delivered the ball."Peter King, NBC Sports

-

"The reporting and background in this book are outstanding."Sports Illustrated

-

"For a man that has completely dominated headlines in Colorado, this is the most complete book about the legend. Jason Cole goes deep with Elway: A Relentless Life, and he delivers on the man who delivered so much for Colorado."Adam Schefter, author of The Man I Never Met

-

"For a man who possesses more natural talent than any quarterback in history, John Elway never had it particularly easy on his path to the top of his profession, nor did he seek any shortcuts. Fueled by a relentlessly competitive nature and a gritty, understated toughness, Elway fought through a series of institutional and interpersonal obstacles to reach his goals, and he wouldn't have wanted it any other way. Jason Cole was fortunate enough to witness Elway's excellence at an early age, and he kept filling up notebooks while chronicling the quarterback's peaks and valleys for the next several decades. Like his subject, Cole is unafraid to go all-in and unbending in his pursuit of success. The result is a comprehensive, uncompromising and thoroughly compelling breakdown of a living legend who continues to chase greatness, every single day."Mike Silver, NFL Network

-

"The exhaustive and excellent tome by Jason Cole about the life and times of 60-year-old John Elway."NBC Sports

-

"Learned so much about No. 7 in Elway, as Jason Cole connected many dots with his well-researched, deep dive into the remarkable career and life of an icon. It is an enjoyable read, too, well-written with an abundance of details and context. Not only is this a must for any given John Elway fan, but it is a treasure that needed to be documented for the sake of football history."Jarrett Bell, NFL Columnist, USA Today Sports

-

"John Elway is one of America's most famous and celebrated sports figures, and yet he's always been something of a mystery. Jason Cole peals back the layers, like only someone who has known Elway since their Stanford days can. Wanna know where the power in his right arm came from? How he survived the Dan Reeves years and excelled under Mike Shanahan? Why he still grinds every day running the Denver Broncos, even with multiple Super Bowl rings and a secure legacy in place? This riveting primer on the requirements of greatness answers them all."Seth Wickersham, ESPN

-

"An in-depth, entertaining biography of one of football's greatest quarterbacks, John Elway.... Cole smoothly takes readers from on-field action to back-office decision-making.... This is a must-read for Elway and Broncos fans."Publishers Weekly

-

"The author convincingly shows that no other quarterback has combined [Elway's] drive, intelligence, willpower, and athleticism, and none has been so relentless in seeking self-improvement and gridiron glory....Cole is a fluent interpreter of the game of football and its arcana, and he has a considered appreciation for what it is that makes a great leader....Fans of the Broncos-and football in general-will enjoy this portrait of one of the game's greatest players."Kirkus Reviews

-

"Engrossing read, very well-researched."Ramon Maclin, Medium.com

- On Sale

- Nov 9, 2021

- Page Count

- 368 pages

- Publisher

- Hachette Books

- ISBN-13

- 9780316455794

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use