Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

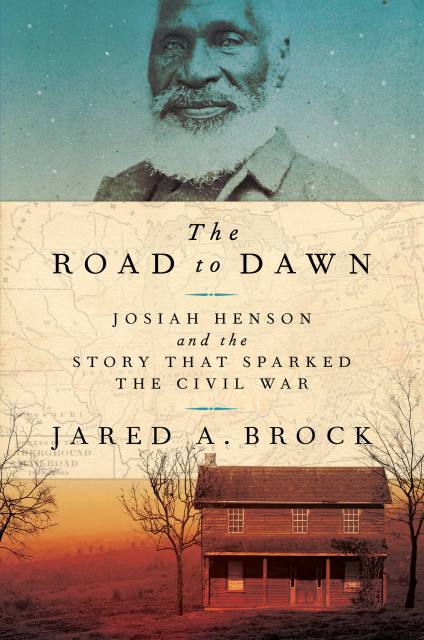

The Road to Dawn

Josiah Henson and the Story That Sparked the Civil War

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$14.99Price

$19.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $14.99 $19.99 CAD

- Hardcover $37.00 $47.00 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around May 15, 2018. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

-He rescued 118 enslaved people

-He won a medal at the first World’s Fair in London

-Queen Victoria invited him to Windsor Castle

-Rutherford B. Hayes entertained him at the White House

-He helped start a freeman settlement, called Dawn, that was known as one of the final stops on the Underground Railroad

-He was immortalized in Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin, the novel that Abraham Lincoln jokingly blamed for sparking the Civil War

But before all this, Josiah Henson was brutally enslaved for more than forty years.

Author-filmmaker Jared A. Brock retraces Henson’s 3,000+ mile journey from slavery to freedom and re-introduces the world to a forgotten figure of the Civil War era, along with his accompanying documentary narrated by Hollywood actor Danny Glover.

The Road to Dawn is a ground-breaking biography lauded by leaders at the NAACP, the Smithsonian, senators, authors, professors, the President of Mauritius, and the 21st Prime Minister of Canada, and will no doubt restore a hero of the abolitionist movement to his rightful place in history.

Genre:

- On Sale

- May 15, 2018

- Page Count

- 320 pages

- Publisher

- PublicAffairs

- ISBN-13

- 9781541773936

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use