Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

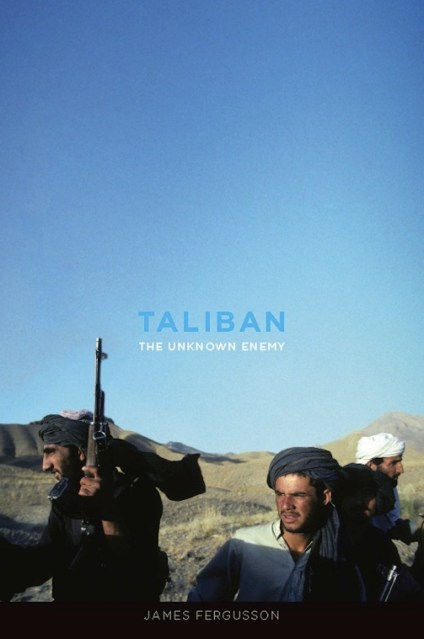

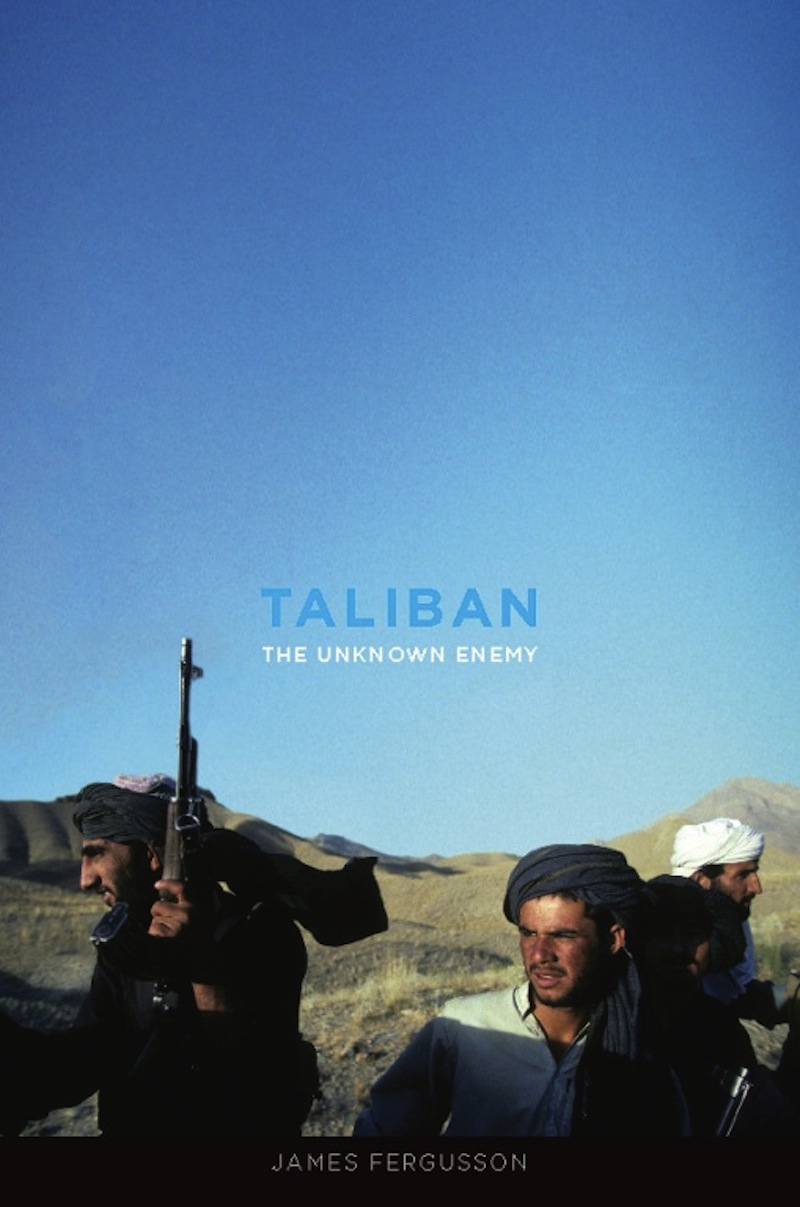

Taliban

The Unknown Enemy

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$11.99Format

Format:

- ebook $11.99

- Trade Paperback $24.99

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around May 24, 2011. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

In this extraordinary and compelling account of the rise, fall, and return of the Taliban, author James Fergusson, who has unique access to its shadowy leaders, presents the reality of themovement so often mischaracterized in the press. His surprising and, perhaps, uncomfortable conclusions about our current strategy in Afghanistan should be required reading for anyone who wishes to understand this intractable conflict.

Genre:

- On Sale

- May 24, 2011

- Page Count

- 432 pages

- Publisher

- Da Capo Press

- ISBN-13

- 9780306820342

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use