Promotion

Shop now and save 20% on your back-to-school purchases & get free shipping on orders $45+ Use code: SCHOOL24

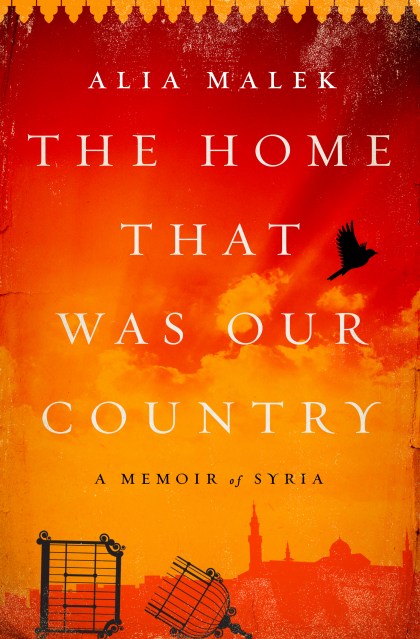

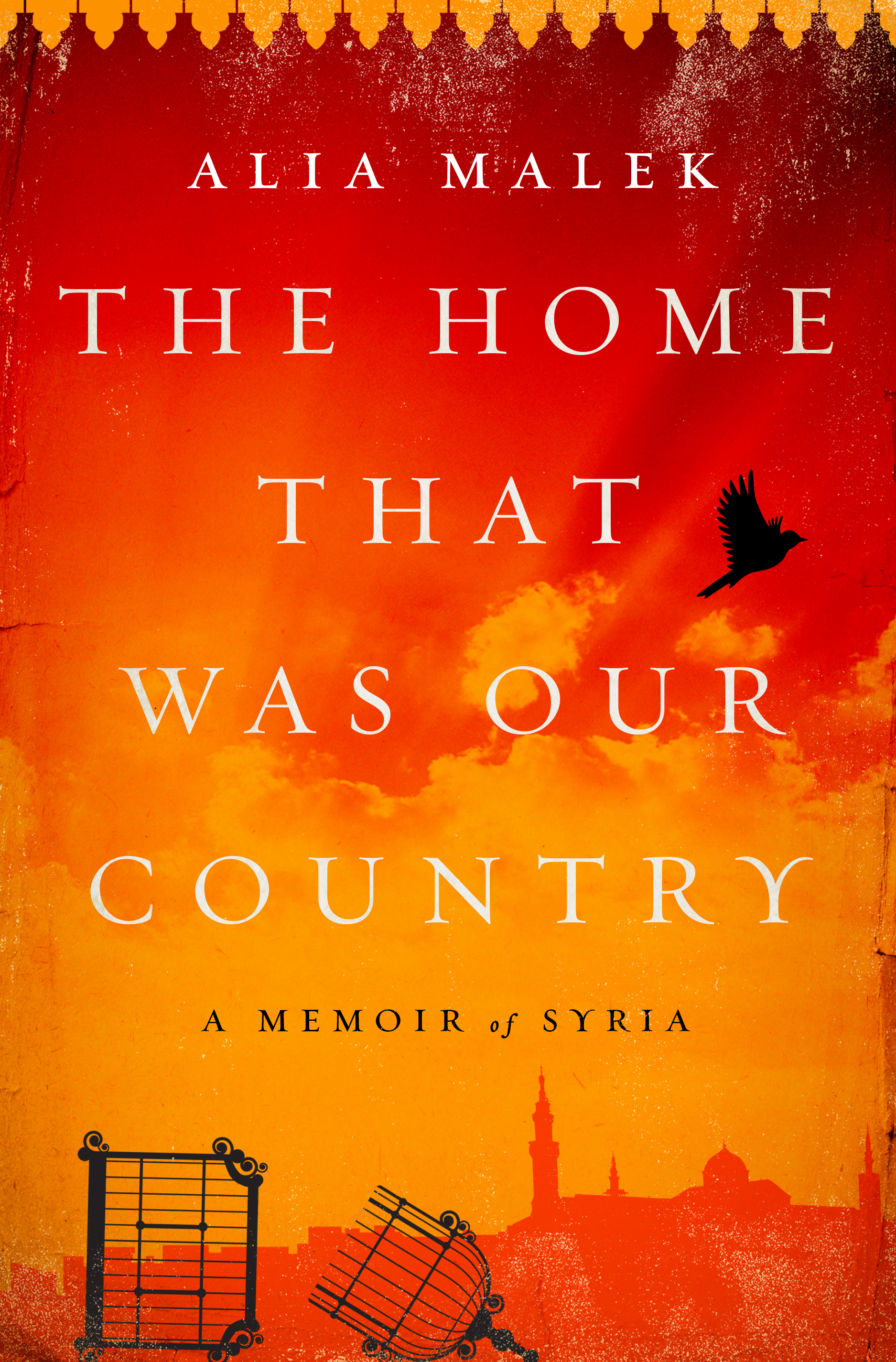

The Home That Was Our Country

A Memoir of Syria

Contributors

By Alia Malek

Formats and Prices

Price

$17.99Price

$22.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $17.99 $22.99 CAD

- ebook $9.99 $12.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around March 13, 2018. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

The Home That Was Our Country is a deeply researched, personal journey that shines a delicate but piercing light on Syrian history, society, and politics. Teeming with insights, the narrative weaves acute political analysis with a century of intimate family history, ultimately delivering an unforgettable portrait of the Syria that is being erased.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Mar 13, 2018

- Page Count

- 368 pages

- Publisher

- Bold Type Books

- ISBN-13

- 9781568588445

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use