Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

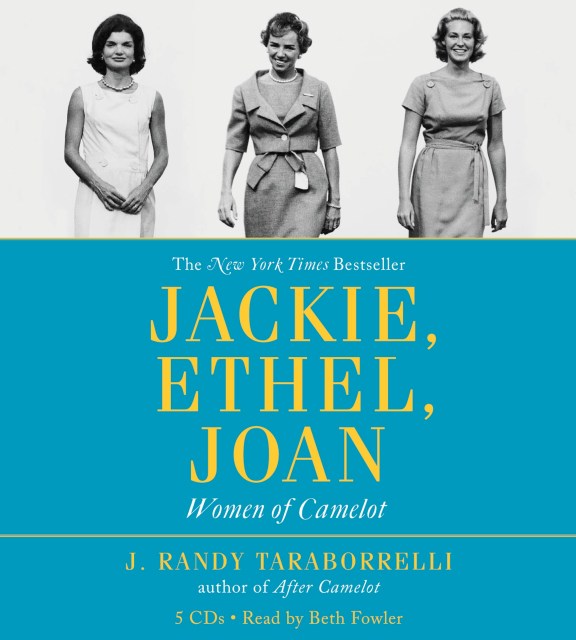

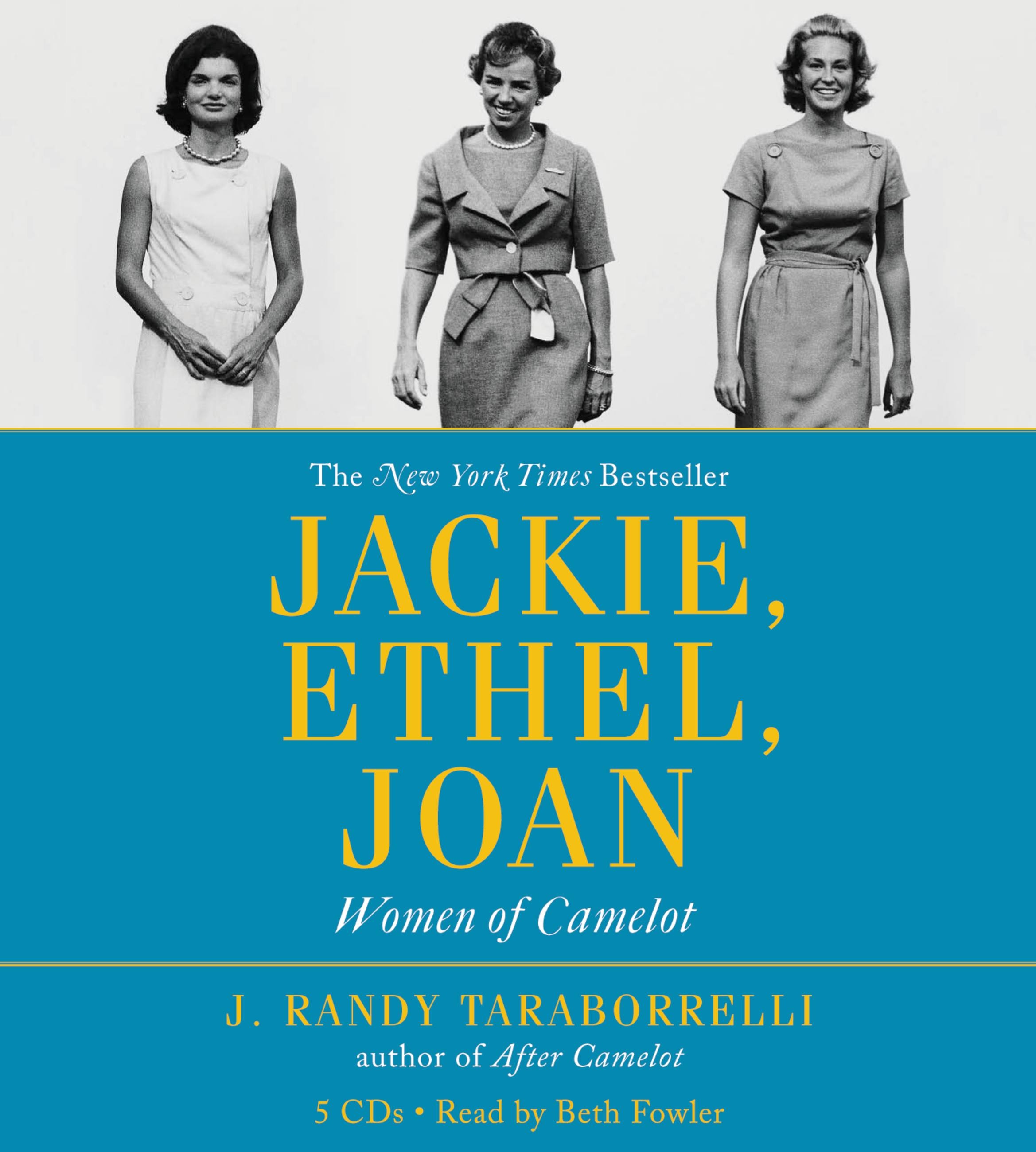

Jackie, Ethel, Joan

Women of Camelot

Contributors

Read by Beth Fowler

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Nov 1, 2005

- Publisher

- Hachette Audio

- ISBN-13

- 9781594834745

Price

$18.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Audiobook Download (Abridged) $18.99 CAD

- ebook $11.99 $15.99 CAD

- Hardcover $46.00 $59.00 CAD

- Trade Paperback $19.99 $24.99 CAD

- Mass Market $32.99 $41.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around November 1, 2005. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Jacqueline Bouvier. Ethel Skakel. Joan Bennett. Three women who married into America’s royal family and became forever linked in legend.

Set against the panorama of explosive American history, this unique story offers a rarely-seen look at the relationship shared among the three women — during the Camelot years and beyond. Whether dealing with their husbands’ blatant infidelities, stumping for their many political campaigns, touring the world to promote their family’s legacy, raising their children, or confronting death, the Kennedy wives did it all with grace, style and dignity.