Promotion

Shop now and save 20% on your back-to-school purchases & get free shipping on orders $45+ Use code: SCHOOL24

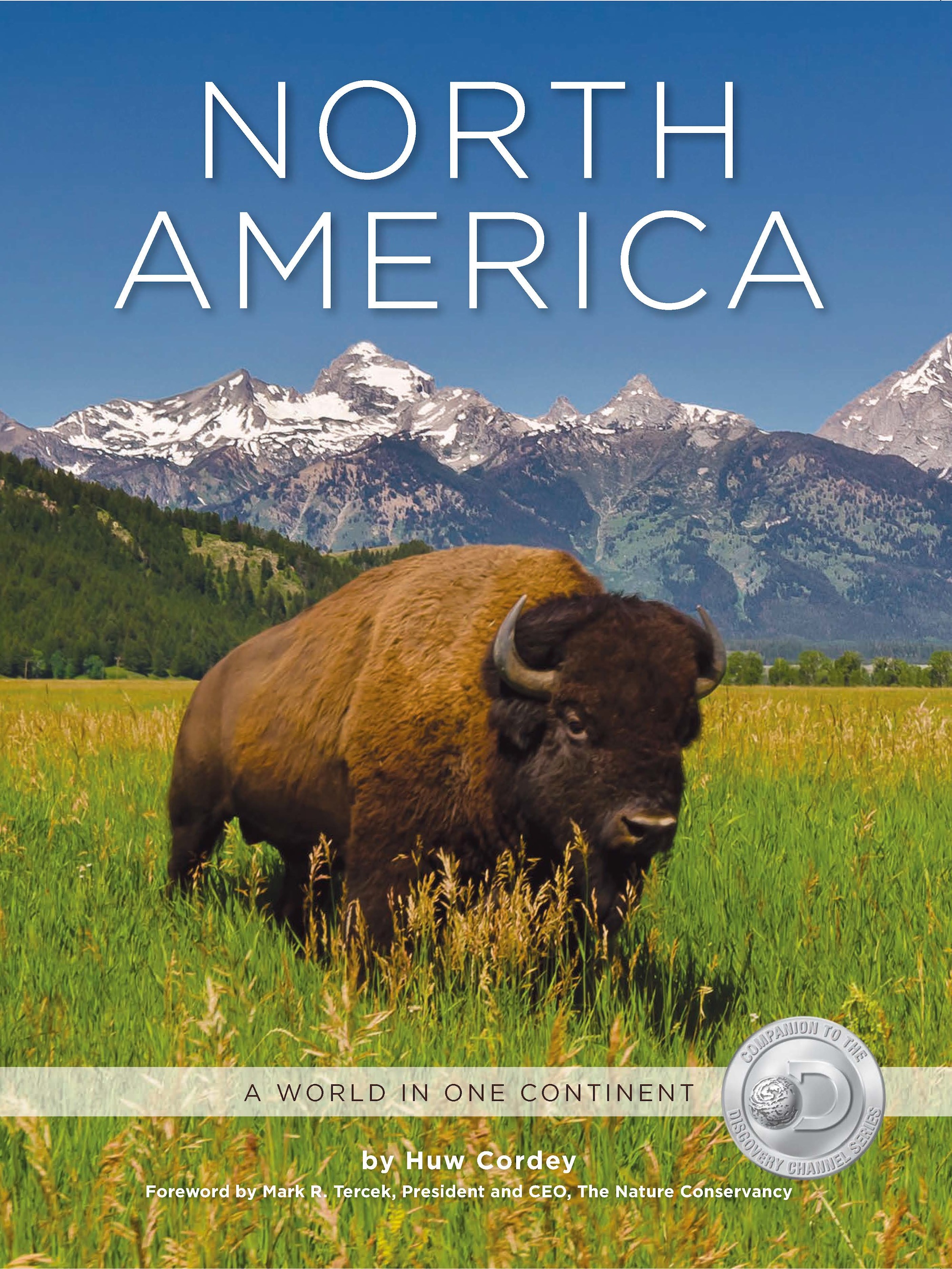

North America

A World in One Continent

Contributors

By Huw Cordey

Foreword by Mark Tercek

Formats and Prices

Price

$20.99Price

$26.99 CADFormat

Format:

ebook $20.99 $26.99 CADThis item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around April 2, 2013. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

In the stunning seven-part series from Discovery Channel, renowned nature producer Huw Cordey travels from the Arctic to the Tropics, revealing the wonders of the most dynamic continent on Earth — from the stunning glow of the Aura Borealis in Alaska to the thousands of tornadoes that batter the Great Plains each year to the 55-ton crystals in Mexico’s Crystal Cave.

North America, the companion book to the television series, follows the producers as they tell the story of this rich and eclectic land through more than 250 gorgeous full-color photographs and engaging essays. Chock-full of interesting facts about the various ecology and wildlife of the many regions of the continent — Prairies, Coasts, Mountains, Freshwater, Deserts, and Forests — North America exposes the continent as you’ve never seen it before.

- On Sale

- Apr 2, 2013

- Page Count

- 288 pages

- Publisher

- Running Press

- ISBN-13

- 9780762448432

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use