Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

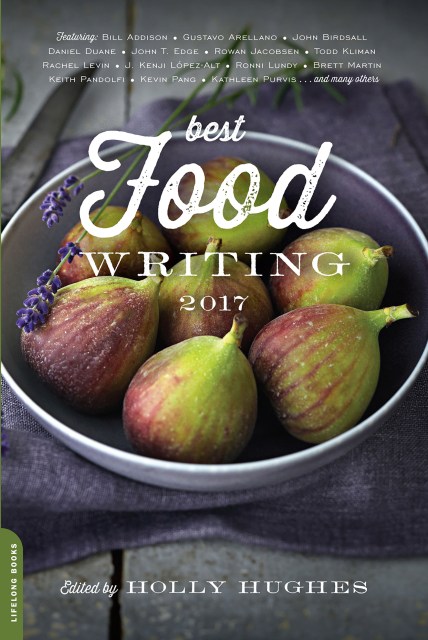

Best Food Writing 2017

Contributors

By Holly Hughes

Formats and Prices

Price

$11.99Price

$15.99 CADFormat

Format:

ebook $11.99 $15.99 CADThis item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around October 17, 2017. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

From small-town bakeries to big city restaurants, Best Food Writing offers a bounty of everything in one place. For eighteen years, Holly Hughes has scoured both the online and print world to serve up the finest collection of food writing. This year, Best food Writing delves into the intersection of fine dining and food justice, culture and ownership, tradition and modernity; as well as profiles on some of the most fascinating people in the culinary world today. Once again, these standout essays–compelling, hilarious, poignant, illuminating–speak to the core of our hearts and fill our bellies. Whether you’re a fan of Michel Richard or Guy Fieri–or both–there’s something for everyone here. Take a seat and dig in.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Oct 17, 2017

- Page Count

- 368 pages

- Publisher

- Da Capo Lifelong Books

- ISBN-13

- 9780738220192

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use