Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

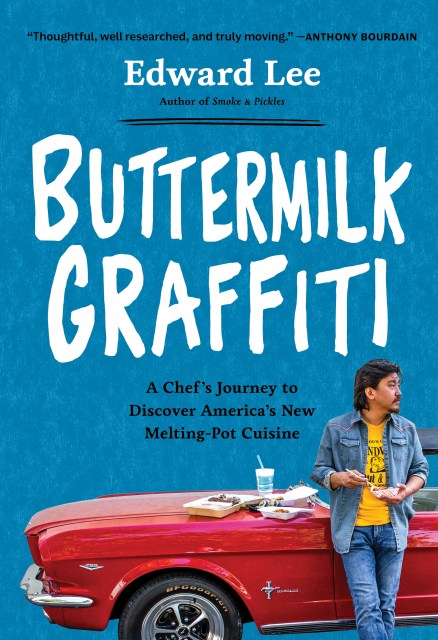

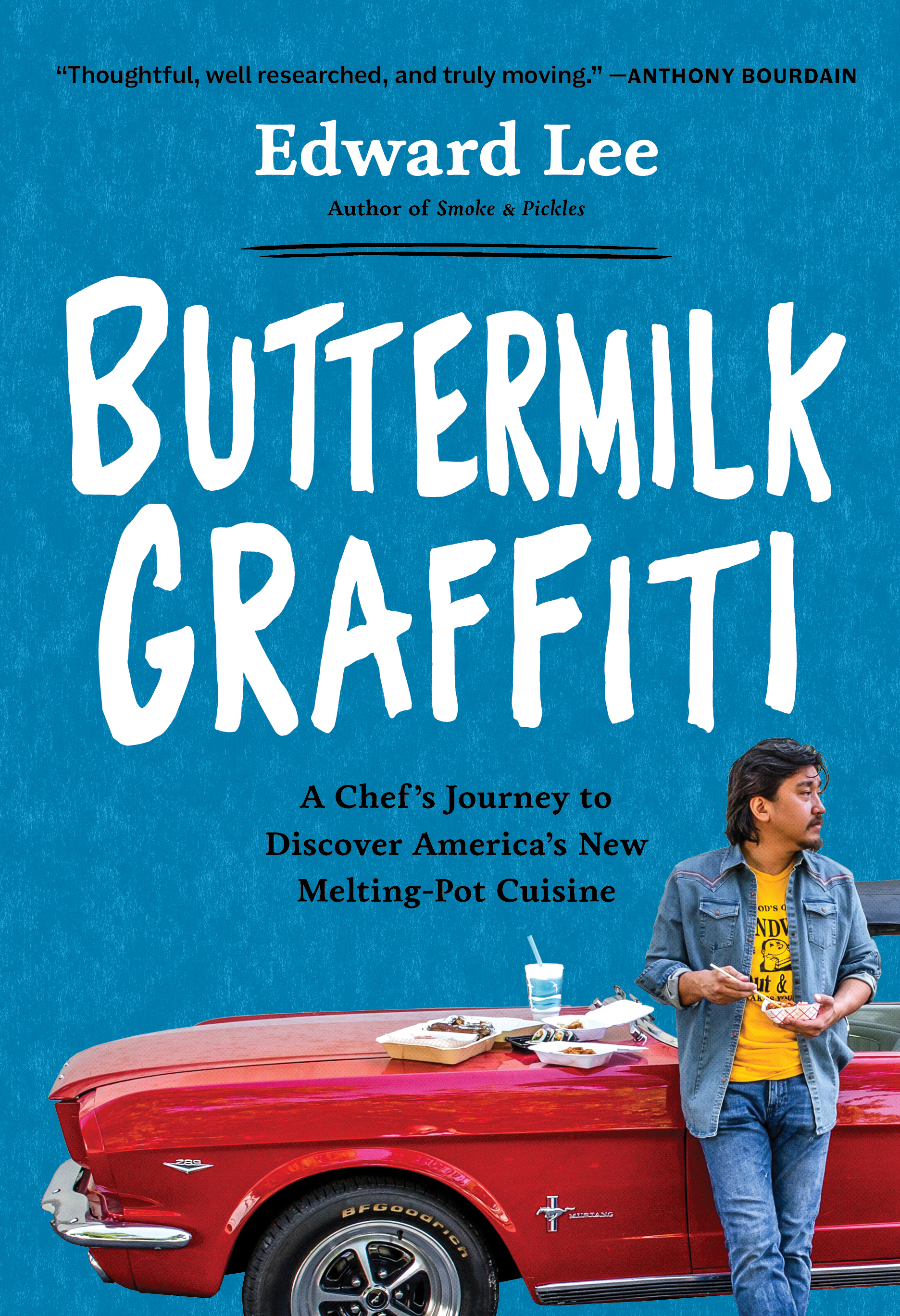

Buttermilk Graffiti

A Chef's Journey to Discover America's New Melting-Pot Cuisine

Contributors

By Edward Lee

Formats and Prices

Price

$16.99Price

$22.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $16.99 $22.99 CAD

- ebook $2.99 $2.99 CAD

- Hardcover $27.50 $37.50 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around March 5, 2019. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

Winner, 2019 James Beard Award for Best Book of the Year in Writing

Finalist, 2019 IACP Award, Literary Food Writing

Named a Best Food Book of the Year by the Boston Globe, Smithsonian, BookRiot, and more

Semifinalist, Goodreads Choice Awards

“Thoughtful, well researched, and truly moving. Shines a light on what it means to cook and eat American food, in all its infinitely nuanced and ever-evolving glory.”

—Anthony Bourdain

American food is the story of mash-ups. Immigrants arrive, cultures collide, and out of the push-pull come exciting new dishes and flavors. But for Edward Lee, who, like Anthony Bourdain or Gabrielle Hamilton, is as much a writer as he is a chef, that first surprising bite is just the beginning. What about the people behind the food? What about the traditions, the innovations, the memories?

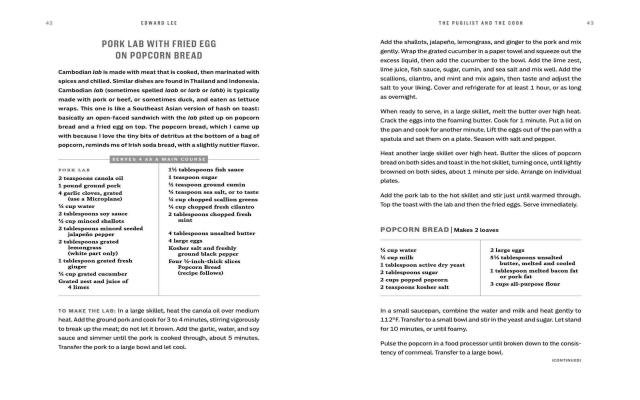

A natural-born storyteller, Lee decided to hit the road and spent two years uncovering fascinating narratives from every corner of the country. There’s a Cambodian couple in Lowell, Massachusetts, and their efforts to re-create the flavors of their lost country. A Uyghur café in New York’s Brighton Beach serves a noodle soup that seems so very familiar and yet so very exotic—one unexpected ingredient opens a window onto an entirely unique culture. A beignet from Café du Monde in New Orleans, as potent as Proust’s madeleine, inspires a narrative that tunnels through time, back to the first Creole cooks, then forward to a Korean rice-flour hoedduck and a beignet dusted with matcha.

Sixteen adventures, sixteen vibrant new chapters in the great evolving story of American cuisine. And forty recipes, created by Lee, that bring these new dishes into our own kitchens.

Finalist, 2019 IACP Award, Literary Food Writing

Named a Best Food Book of the Year by the Boston Globe, Smithsonian, BookRiot, and more

Semifinalist, Goodreads Choice Awards

“Thoughtful, well researched, and truly moving. Shines a light on what it means to cook and eat American food, in all its infinitely nuanced and ever-evolving glory.”

—Anthony Bourdain

American food is the story of mash-ups. Immigrants arrive, cultures collide, and out of the push-pull come exciting new dishes and flavors. But for Edward Lee, who, like Anthony Bourdain or Gabrielle Hamilton, is as much a writer as he is a chef, that first surprising bite is just the beginning. What about the people behind the food? What about the traditions, the innovations, the memories?

A natural-born storyteller, Lee decided to hit the road and spent two years uncovering fascinating narratives from every corner of the country. There’s a Cambodian couple in Lowell, Massachusetts, and their efforts to re-create the flavors of their lost country. A Uyghur café in New York’s Brighton Beach serves a noodle soup that seems so very familiar and yet so very exotic—one unexpected ingredient opens a window onto an entirely unique culture. A beignet from Café du Monde in New Orleans, as potent as Proust’s madeleine, inspires a narrative that tunnels through time, back to the first Creole cooks, then forward to a Korean rice-flour hoedduck and a beignet dusted with matcha.

Sixteen adventures, sixteen vibrant new chapters in the great evolving story of American cuisine. And forty recipes, created by Lee, that bring these new dishes into our own kitchens.

Genre:

-

“Striking stories. . . . Lee is a master.”

—New York Times Book Review“Beautifully written.”

—NPR

“Lee is a gifted storyteller and those first few chapters will grab you and keep you riveted all the way to the end.”

—Bon Appétit

“Capture[s] what the nation’s melting pot cuisine is today.”

—Food Wine, Staff Favorite

“Part adventure tale, part memoir. . . . Don’t hit the beach without this remarkable book in your bag.”

—Fine Cooking

“Conjure[s] writers as diverse and compelling as Alexis de Tocqueville, M.F.K. Fisher and Anthony Bourdain. . . . Powerful, poignant, and timely.”

—Atlanta Journal-Constitution

“Lee peels open the layers of what it means to be American today. . . . [Buttermilk Graffiti] contains a level of awareness that’s often missing from chef memoirs. . . . Lee is just as well-read and reflective as master of the genre Anthony Bourdain, but he brings a fresh take.”

—Eater

“Raw, gritty. . . . Each chapter in Buttermilk Graffiti presents a new adventure.”

—Richmond Times-Dispatch

“Lee is consistently willing to dive into unfamiliar places and challenging conversations to get stories that haven’t yet been told, and the reader emerges from Buttermilk Graffiti richer for his efforts. . . . Buttermilk Graffiti represents exactly the kind of inquiry that helps create a vibrant national food scene. It’s not a flavor-of-the-week Nutella lasagna recipe turned hashtag, and it’s not a reality food competition. The book is one hyper-curious chef, on the road, meeting people in places that haven’t already been covered to death and discovering what they eat and what makes it special. Based on the stories that Lee tells, the journey was valuable unto itself—and we’re just fortunate to get to tag along with him.”

—Christian Science Monitor

“A tapestry of American cuisine. . . . Lee’s elevation of the often anonymous people behind the food we eat speaks to his concern with not just style, but substance.”

—Los Angeles Times

“Like all great food writers, [Lee is] always on the verge of declaring the thing he is currently chewing on to be among the greatest things he’s ever eaten. He will eat two West Virginia slaw dogs before 8 a.m. and stay up all night on your porch drinking whiskey. . . . He’s so amiable that as you read the book, you can easily imagine that he’s a friend.”

—The Wall Street Journal

“A great romp of a read with humor, poignancy, and—for people who love food—a page turner.”

—Edible DC

“Altogether eye-popping. . . . Buttermilk Graffiti is a timely and important work that reminds readers that America’s melting pot is alive and well in the most unexpected places. And, that we all belong.”

—New York Journal of Books

“Excellent. . . . Lee celebrates unexpected confluences of cuisines while refusing to be limited by definitions of ‘authenticity.’”

—Publishers Weekly, starred review

“An acclaimed chef and restaurateur travels across the country to explore the cultural history behind the evolving American cuisine. Lee . . . points out the essential role that both immigrants and longtime settlers play in the food we eat. . . . A heartfelt and forward-thinking book.”

—Kirkus Reviews

“At a time when America’s melting-pot culture frightens so many citizens, Lee finds hope and joy in visiting ethnic communities all across the nation’s breadth.”

—Booklist

“Part adventure tale, part food treatise, part memoir, Buttermilk Graffiti is all Edward Lee: wide-eyed, profane, hungry for life, ever soulful, and poetic. In prose that’s as gorgeous and honest as his cooking, Lee takes us on an irresistible journey into the amazing diversity of flavors and traditions that truly makes this country great. An essential American story.”

—Chang-rae Lee, winner of the PEN/Hemingway Award and Pulitzer Prize finalist

“Restlessly curious, unafraid, and empathetic, Edward Lee reports and writes like a narrative journalist with a side interest in squash schnitzel and pickle juice gravy. You won’t read a smarter book about American food culture this year.”

—John T. Edge, author of The Potlikker Papers: A Food History of the Modern South

“With the release of Buttermilk Graffiti, Edward Lee proves himself to be one of our country’s great chroniclers of culture. Going all the way back to de Tocqueville, the most informative and impactful writing has examined class, society, culture, assimilation, and food. Lee now joins that long list of food/culture warriors, deciphering our modern world through what we can learn from its food and inspiring us to look at what we eat, where it comes from, who is cooking it, and why. In today’s political and social climate, this book is as timely as it is important.”

—Andrew Zimmern, chef, teacher, author, and host of Bizarre Foods with Andrew Zimmern

“Buttermilk Graffiti is a masterfully narrated passion tour of some of this country’s most revelatory places to eat and the people behind them, written in Edward Lee’s socially conscious style. It left me enlightened and hungry.”

—Toni Tipton-Martin, author of The Jemima Code: Two Centuries of African American Cookbooks

- On Sale

- Mar 5, 2019

- Page Count

- 320 pages

- Publisher

- Artisan

- ISBN-13

- 9781579659004

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use