Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

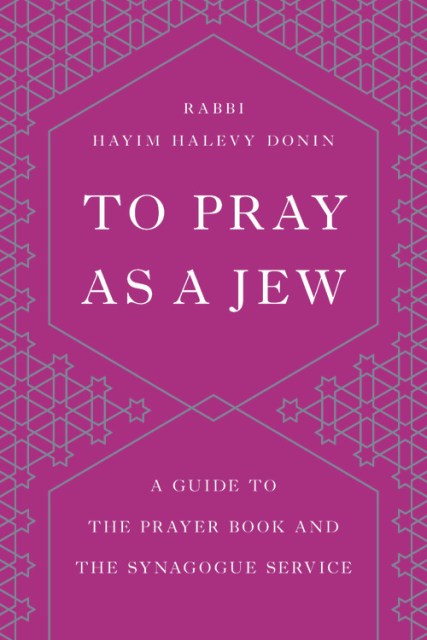

To Pray as a Jew

A Guide to the Prayer Book and the Synagogue Service

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$21.99Price

$28.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $21.99 $28.99 CAD

- ebook $13.99 $17.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around August 13, 2019. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

A distinguished guide to Jewish prayer

Why do Jews pray? What is the role of prayer in their lives as moral and ethical beings? From the simplest details of how to comport oneself on entering a synagogue to the most profound and moving comments on the prayers themselves, Rabbi Hayim Halevy Donin guides readers of To Pray as a Jew through the entire prescribed course of Jewish liturgy, passage by passage, ritual by ritual, in this handsome and indispensable guide to Jewish prayer.

Unexcelled for beginners as well as the religiously observant, To Pray as a Jew is intended to show the way, to enlighten, and hopefully to inspire.

Unexcelled for beginners as well as the religiously observant, To Pray as a Jew is intended to show the way, to enlighten, and hopefully to inspire.

Genre:

-

"A lucid and sensitive guide for those who would like to pray Jewishly but don't know how....A boon to both Jewish teachers and laymen."Hadassah Magazine

- On Sale

- Aug 13, 2019

- Page Count

- 496 pages

- Publisher

- Basic Books

- ISBN-13

- 9781541674035

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use